Alcohol

During this, Mr Szprott was arranging three tankards on the table and uncorking three bottles. ‘Now, just look, Ignacy,’ said the councillor, raising a brimming tankard, ‘the colour of old mead, froth like cream and it tastes like a sixteen-year-old girl.’ (657)

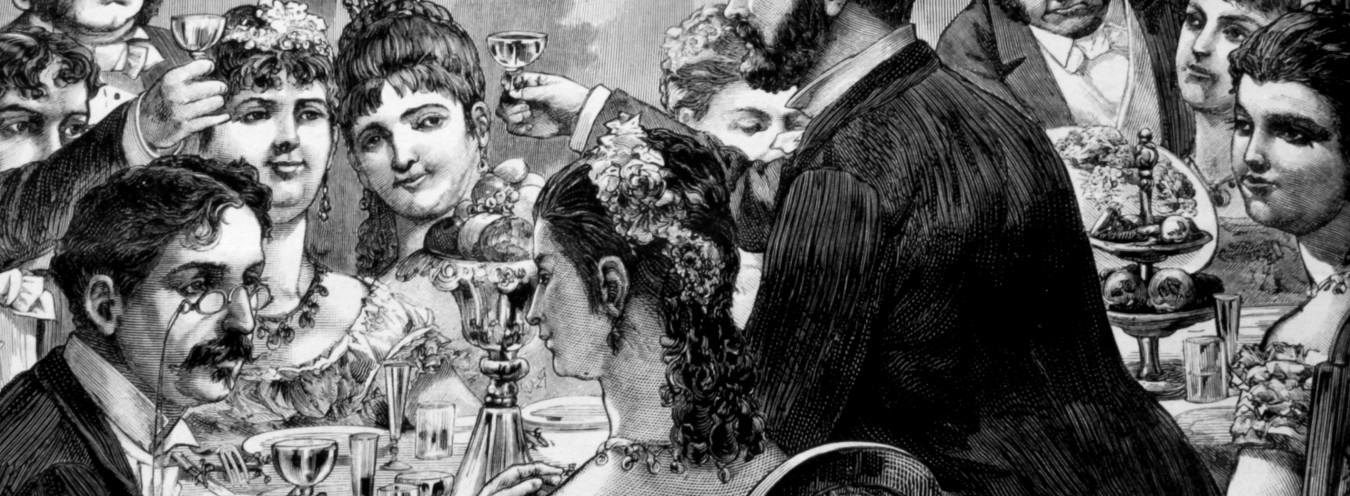

The reader of The Doll first encounters the company of J. Mincel and S. Wokulski as seen through a bottle [of beer] by Warsaw tradesmen and members of the intelligentsia who come to a celebrated restaurant in Krakowskie Przedmieście. Ignacy Rzecki, the senior clerk in Wokulski’s store, also enjoys his evening visits to a bar to down a few pints, either alone or in the company of Councillor Węgrowicz and travelling salesman Szprott. This detail is consistent with the actual drinking habits of that time: the middle class continued to sip beer despite the immense popularity of vodka (which was a number one drink of choice among students and the poorest inhabitants of nineteenth-century Warsaw) as well as its easy availability (as of 1873, there were almost 400 vodka places in Warsaw alone). Unfortunately, it is impossible to identify the actual establishments that Rzecki could have frequented except for the restaurant of Antoni Wolski in Rezler and Hurtig’s building at Krakowskie Przedmieście 79.

In the 1870s, Warsaw boasted over 80 beerhouses. Their signs depicted bottles with beer pouring out into mugs or extended arms holding up tankards; all inscriptions were in both Polish and Russian, with the same-sized Roman and Cyrillic letters. Beer was also sold outdoors, e.g. during horse-racing in the Mokotów race-course, where hawkers cried their beer, sausage-rolls and oranges for sale. The types of beer included Bavarian, English ale, March-type lager (lightly fermented beer), and dark, strong porter. Rzecki was a big fan of the last variety: A glass of anisette and a portion of herring at the counter, then a small portion of tripe and a carafe of porter at my table – quite a feast!

Moreover, it is with beer that Wokulski washes down sirloin during an elegant dinner at the Łęckis. That should not come as a surprise: beer was so popular that both men and women drank it as they would mineral water, even while watching a show in the theatre.

The main characters of The Doll never drink cheap vodka, which had a very poor reputation; the press reported multiple cases of alcohol poisoning and even death caused by “the sauce.” Only once, at the culmination of the main plot, Wokulski orders vodka in the buffet at the Skierniewice train station: ‘Vodka!’ he exclaimed. Surprised, the waitress handed him a glass. He lifted it to his lips, but felt a pressure in his throat and nausea, so put down the glass untouched.

When the novel’s characters reach for spirits, they choose quality vodkas and liqueurs (anisette), arrack distilled from rice, palm syrup or sugar cane (commonly taken with tea and coffee), coffee cocktail with cognac served in one glass or, like in a Paris café, as coffee and a carafe of brandy marked with little lines which indicated the contents of a glass. Dizzy with Paris life and obsessed with jealousy over Izabela, Wokulski does not act himself: he gets drunk on brandy and dozes off at his table, much to other customers’ merriment.

After climbing up the social ladder, Wokulski – the former clerk in Hopfer’s cellar – attends the nobility’s social occasions and parties and follows the relevant alcohol etiquette of wine and champagne. Only once does the author mention the specific type of wine: port-wine (sweet red wine from Portugal) served at the Łęckis’ and drunk by Wokulski right after consommé.

However, on his return from the Russo-Turkish War, the protagonist does not need to worry about etiquette. When Rzecki opens a bottle of reasonable Hungarian wine to celebrate the event, Wokulski drinks it from a tumbler (for lack of two wine glasses) and talks about the financial success of his Bulgarian venture. Back then, everything still seemed possible…

→ Cuisine; → Restaurants and Cafés;

Bibliografia

- D. Kałwa, Polska doby rozbiorów i międzywojenna, in Obyczaje w Polsce. Od średniowiecza do czasów współczesnych, ed. A. Chwalba, Warsaw 2004.

- S. Milewski, Ciemne sprawy dawnych warszawiaków, Warsaw 1981.