Ir and Other Animals

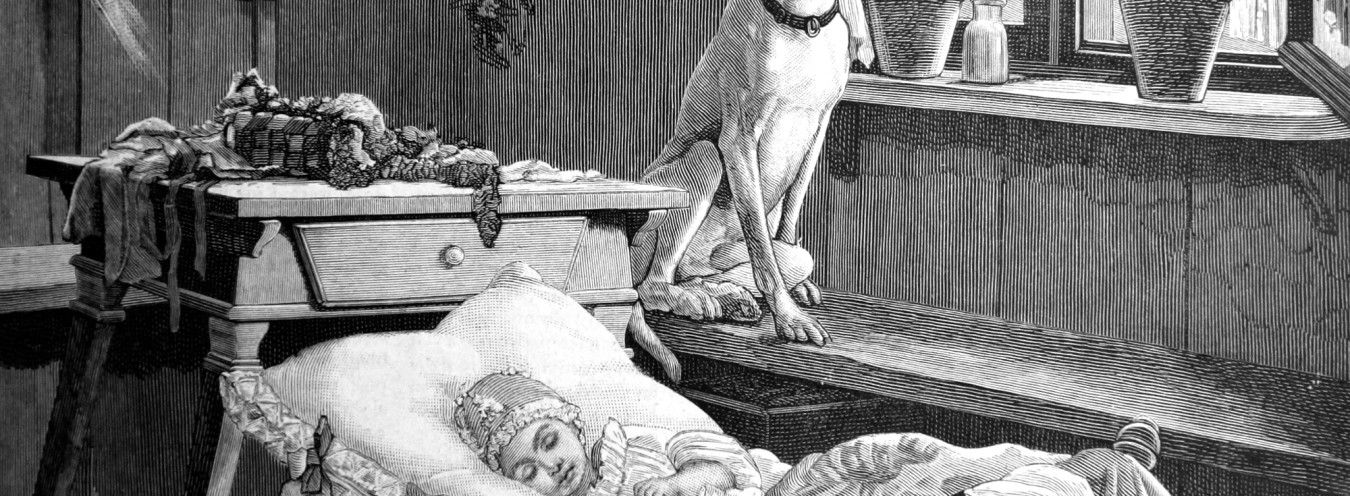

[Illustration 20. Dog, A. Kędzierski]

The novel abounds in both brief mentions and complex stories of animals, but for Prus, the representatives of fauna gain most significance if their destinies are closely related to the lives of people. They include not only domestic animals and pets, such as Helena Stawska’s canary bird, but also the swans fed by Wokulski and Izabela on their boat trip or even the gudgeon caught by Julian Ochocki, angling with bored ladies at the summer retreat. Nature in the wild is mentioned only figuratively: wolves, hippopotamuses, or bats are fairytale characters, symbols of higher laws, or elements of a scientific personality typology. The epoch’s fascination with technology is reflected in the presence of artificial animals: mechanical toys. We know how much Rzecki enjoys watching the bear climbing a pole, the crowing cock, and the mouse fleeing a cat; we remember the toy animals that he gives Helena Stawska’s daughter.

In the anthropologically- or even sociologically-oriented menagerie of Prus, the most numerous and detailed descriptions represent dogs and horses. In the metropolitan scenery of Warsaw or Paris, horses harnessed to carriages, coaches, or wagons loaded with goods are ubiquitous, but they attract the narrative attention in their moments of suffering. Brutally whipped or sentenced to death because of a broken leg, they embody pain in its pure form; those representations of cruelty become the novel’s topos. Mounts are more fortunate than draft animals. As horse aristocracy, they participate in the leisure activities of the upper classes and sometimes even witness – as Kazimiera Wąsowska’s horse – their adventures and love affairs. The most important representative of the horse family is the racemare that Wokulski buys from the Krzeszewskis. He enters her for the race as Sultanka and wins prize money for the run. He worries about the mare’s condition, caresses her tenderly, and is even concerned about her in his dreams. This beautiful and expensive animal becomes a key figure in the scheme for prestige in the upper crust and more specifically for Izabela’s favour.

The presence of dogs is even more personalised as the fates of all three pets in the novel are closely related to the lives and temperaments of their owners. Mrs Meliton takes in her dog from the streets immediately after the funeral of her drunkard husband. She is convinced that her new friend will be the most grateful of creatures. Unfortunately, the dog contracts rabies, bites her servant, and as a result drives Mrs Meliton into illness and makes her lose trust in people and the world. In contrast, the mutt watching the estate in Zasławek bares his teeth and barks loudly, but, as Wokulski discovers when stoking the delighted dog, his joyful eyes and wagging tail reveal a cheerful personality. In Duchess Zasławska’s estate, a utopian land, even a “bad” watchdog is necessarily good. Yet the most attention is the novel is devoted to Ir, Rzecki’s poodle. He is the only dog with a name and a background story. We know that he has lost one eye, sleeps on a sofa bed, drinks milk from a bowl, and scratches the door in the morning to signal his need to go out. He is intimately close to Ignacy Rzecki: he barks at his owner when he returns home tipsy or when he wakes him up too early with loud sounds of morning bathing. Rzecki understands that the poodle is disturbed by the look of his skinny body. The dog’s care and directness is reciprocated by the owner: only towards him does Rzecki, a Hungarian infantry lieutenant, use a blunt soldierly tone (Shut up, you confounded thing!). The poodle shares Rzecki’s dogged devotion to Wokulski, and, in turn, Wokulski treats the animal as caringly as he does his friend (e.g. when helping them move to a new apartment, he does not forget about Ir’s blanket). The relationship between Ir and his owner seems to have an existential dimension. Exactly in the middle of the novel, we read the last, brief mention of him: Ir is unwell, and we can only imagine what follows. The enigmatic departure or rather disappearance is the key technique in the final parts of The Doll, but the unverbalised death of the animal may also trigger associations with the silent death of the old clerk. The parallel between the two deaths is not explicit yet it is certain that the dog and the owner have grown to resemble one another in their life together. The good old, slightly dirty pet that devotedly shares the bachelor’s loneliness is marked by one single feature that recurs throughout the text – his lost eye. Does not this disability link him to his owner, who perceives both politics and Wokulski’s exploits in a one-sided way and remains blind to the other, more important side of life? Another element that reinforces the affinity between Rzecki and his dog is the latter’s name. What does the mysterious “Ir” stand for? The novel does not provide any explicit explanation, but aren’t these simply Ignacy Rzecki’s initials?

→ Rzecki, Ignacy; → Toys;