Zanzibar, or fantasy versus reality

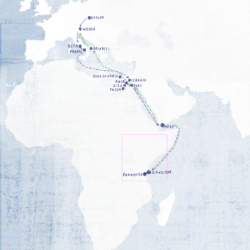

The ship called at the city of Zanzibar on February 16. During their two-week stay there, Sienkiewicz spent a lot of time in the hotel, went sightseeing, and strolled up and down the seaside boardwalk, while Tyszkiewicz was happy to play tennis with the English.[1] Apparently, they left the city only twice: to join a surprise party held onboard an English battleship, and to take part in a trip organized by missionaries (which tired Sienkiewicz so much that he skipped that evening’s reception at the consulate). It is easily noticeable, especially in Tyszkiewicz’s account, that Sienkiewicz was mostly weary and reluctant to leave his hotel room (in Italy, Egypt, as well as in Zanzibar).

Our travelers attend the parties in tailcoats they have fortunately remembered to take with them on their journey, and dinners are served in line with European etiquette (though with the addition of the local color):

We could hear the sound of Indian Ocean waves in the dark outside. The dining hall was lit up just like the ones in Paris and London residences of the affluent, but terrace doors were open to the view of the Crux constellation shining brightly in the sky. Indian domestics in smart outfits, their beards dyed purplish red, were serving European dishes to ladies in décolleté dresses and gentlemen wearing white ties. All of a sudden, I recalled an anecdote about a bathing Englishman who escapes the jaws of a crocodile right up to a palm tree – and uses palm leaves to make himself a pair of gloves and a tie. One would be foolish to even think of heading for the African interior without a tailcoat. You are most certainly going to need it: after all, by Lake Tanganyika, on Ukerewe Island, in Uidjidjia or any other place with a dozen or so “j’s” in its name, you will encounter an English lady determined to accompany her husband to the ends of the world. She will don a low-cut dinner dress to dinner, he will put on his impeccable frock coat (and a white tie) to treat you to pale ale. The English stay the same, no matter where they live.[2]

A question arises about the image of himself that Sienkiewicz wanted to project in Africa and the person he actually was at that time. His reluctance to build a rapport with Tyszkiewicz seems to suggest that he wanted to get away from the company of Poles and thus have some rest from relations and responsibilities he was obliged to keep up every day back at home. On the other hand, he carried multitudinous letters of introduction, which ensured he was received like royalty. Not only did he receive an invitation to the consul’s party, but Tyszkiewicz also recounts an even more telling incident. Sienkiewicz’s hat was blown into the sea on the cruise from Zanzibar to Bagamoyo – and the English passenger steamer turned back especially to retrieve the lost item for him.[3]

It was only in Zanzibar, while they were waiting for the caravan to form, that our travelers decided where exactly they wanted to go. The private correspondence sent to many different addressees and Sienkiewicz’s published letters both indicate that he preferred to rely on local missionaries in practically every aspect of the journey. He realized beyond all doubt that the Mount Kilimanjaro plan was completely unfeasible:

I’ve already mentioned that my primary objective was to climb Mount Kilimanjaro […] about one month’s forceful march away from Bagamoyo. The Maasai tribe who inhabits the vicinity of the mountain is warlike and merciless […]. So, it is no laughing matter […]. With real regret, I had to renounce this trip for a number of reasons. […] First, we needed to face the fact that neither of us has the experience necessary for such a goal, and that all I know about Africa is only textbook knowledge. I could make up for this ignorance with vigor if my health was intact, but it just happens that I got quite ill in Egypt and have half my usual strength left.[4]

Let us stop for a minute on the Kilimanjaro project to acknowledge the fact that it was pure fantasy without even the smallest chance of success. The loop itinerary which was eventually – and only just – covered by Sienkiewicz was approximately 150 kilometers long, while the distance from Bagamoyo to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro is over 500 kilometers. Aside from the problems with high-mountain climbing, including altitude sickness and the freezing cold (that Sienkiewicz was unlikely to know about), even if the travelers turned back before reaching the summit, they would still need to walk a stretch at least six times as long as they did, which would take proportionally more time (no less than three months). Irrespective of all these and other weak points of the scenario, it would surely last into the rain season.

The difficulties listed by Sienkiewicz were easy to predict already from Europe, but it would have required the writer to rely on more authentic accounts than the fantasy of Verne’s artistic vision. Arriving in Zanzibar was most probably when the dream first clashed with reality. It becomes clear that Sienkiewicz definitely had less strength and energy than back in America, and he may also have been much less curious about the world.

Another revealing passage reads:

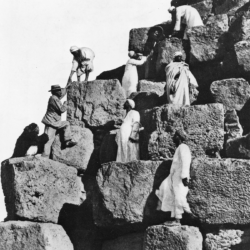

In Africa, the only way to move around is on foot. Let us now imagine a man accustomed to traveling on a train, a horse-drawn carriage, or a ship; taking his meals at regular times; going to sleep in a comfortable bed; taking shelter in bad weather. This man suddenly finds himself in wild countries, where he walks vast distances every day, sleeps in a tent on almost bare ground (sometimes even in the open), eats just about anything, drinks water that is the color of white coffee or hot chocolate, gets wet every time it drizzles and burnt every time the sun comes out. He seems virtually doomed to come down with yellow fever.[5]

The fact that it took so long for Sienkiewicz to realize how difficult it was to move around in Africa is one thing; an even more interesting aspect is his approach to traveling itself. In all likelihood, it is inadvertently that Sienkiewicz expresses an opinion that is almost exactly the opposite to the one he held during the American adventure (when traveling on his own was somehow seen as the beginning of the actual journey). It is true, however, that the present expedition is far from the ideal of the American minimalistic lifestyle:

At this point, we deserved some rest, but unfortunately, we had to play the role of stewards. People who have never had to perform this function may think this is but a trifle, but all this fuss is actually the most disagreeable aspect of the journey. Some cases are padlocked: just try to find the right key. Canned food is secured with reed stems, but tags have come off the tins because of the heat and humidity: just try to guess what’s inside! You need to open the cans on your own and not entrust the task with a local, who will squeeze your main meal together with sauce onto the ground. Your translator is gone, he took off into the woods. Without him, the cook does not understand you nor you the cook, so if you want to eat a bit better, that is: you do not want tea sprinkled on your vegetables, sugar in your sausages, salt in your coffee – you have to look to everything yourself. And this means sitting by the fire when it’s already over forty degrees Celsius around you.[6]

The African reality check made it necessary to find something that would give the stay some sort of focus. The choice fell on hunting:

“To be honest, I do not care if I get to Morogoro or not. The place holds no interest for me, and I decided to take any longer stopovers only where there is abundant game for hunting.”[7]

Przypisy

- “What a great lawn tennis court”, he wrote about one of the many things that generated his excitement (J. Tyszkiewicz, op.cit., p. 101; trans. J. M.).

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z Afryki [Letters from Africa], op.cit., p. 91; trans. J. M.

- J. Tyszkiewicz, op.cit., p. 101; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z Afryki [Letters from Africa], op.cit., pp. 109–110, emphasis B. Sz.; trans. J. M.

- Ibidem, p. 112; trans. J. M.

- Ibidem, p. 233; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 5, part 1, op.cit., p. 334; trans. J. M.