Holiday

‘In any case, you ought to go to the country at once,’ [Kazimiera Wąsowska] continued. ‘Who ever heard of anyone staying in town at the beginning of July?’ (632)

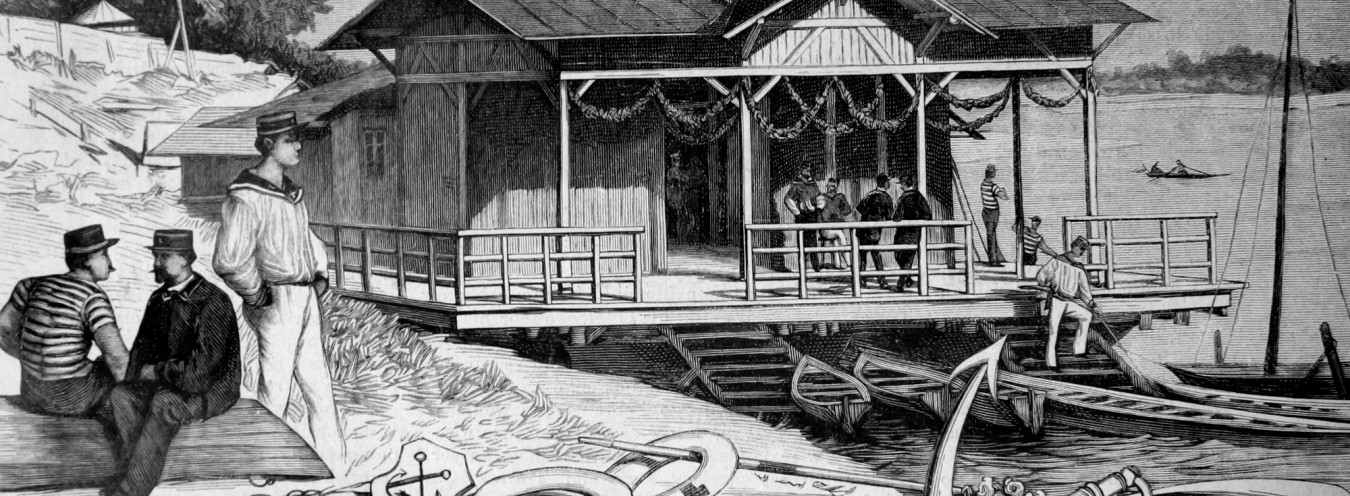

Leaving the city for a summer holiday became extremely popular in the second half of the nineteenth century. All Varsovians, irrespective of their social position or financial standing, dreamt of spending some time outside Warsaw. Tired of constant city noise and confined space, they escaped to the countryside, where – Prus states in his Kartki z podróży (Travel Notes) – they could respire more freely without the need to fight a crowd of consumptives for a breath of air.

The wealthy would spend the summer in their country houses, visit European capitals or leave for foreign spa resorts such as Karlsbad, Davos, and Wiesbaden. Izabela Łęcka wishes for a holiday in Switzerland, but in the end has to settle for taking up Duchess Zasławska’s invitation to her rural estate. Numerous other guests include Julian Ochocki, who does not find Zasławek’s pastimes to his liking: ‘I’ve wasted two months fishing, picking mushrooms, entertaining ladies and such-like nonsense. […] I was going to Paris, but the Duchess insisted I should have my holiday here. A fine holiday I’ve had!’

Varsovians of more modest means opted for Polish resorts such as Zakopane, Krynica, Sopot, Ciechocinek, and Nałęczów, where Prus himself spent as many as 28 summers in a row!

Still, even this form of vacation was unaffordable to most Varsovians due to a high room and board cost as well as travel expenses – not to mention the fact that, for many, leisure itself was an unattainable luxury. Much to Rzecki’s regret, Wokulski may take time off work whenever he wants; but, after all, he isn’t a common-or-garden clerk who has to obtain leave from his master for a holiday once every few years. Ordinary people needed to limit themselves to spending their vacation in the Warsaw area, which was an option much less attractive but more accessible in terms of money and time. Thanks to a dense railway network, it was relatively easy to hire rooms or even houses in the region’s towns and villages that developed around train stations. Prus is quite specific in his Kartki z podróży: quite close to Warsaw, e.g. in Mińsk, Sobolew and Grodzisko, one can find some charming holiday flats. A number of Varsovians commuted every day from “summer lettings” to work in Warsaw. Others visited their vacation-taking wives and children only on the weekend. Once the summer ended, vacators – or rather: vacationers returned to the tumultuous Warsaw.

Not everyone in the novel gives in to the holidaymaking fever. Take Rzecki, for example. He keeps dreaming about going on vacation. He even buys a ticket and gets on the train but jumps out just before the departure, confessing to himself: I can’t leave Warsaw and the store even for a little while.

→ Travels of the Characters in “The Doll”; → Prus’s Travels;

Bibliografia

- B. Prus, Kartki z podróży, vol. 1–2, Warsaw 1950.

- M. Olkuśnik, Podmiejska wilegiatura warszawiaków u schyłku XIX wieku jako zjawisko kulturowe i społeczne, “Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej” 2001, vol. 4.

- M. Olkuśnik, W dalekiej podróży, na wilegiaturze, za rogatkami… O znaczeniu form wypoczynku poza miastem dla badań nad stratyfikacją społeczeństwa Warszawy przełomu XIX i XX w., in Społeczeństwo w dobie przemian. Wiek XIX i XX, Warsaw 2003.