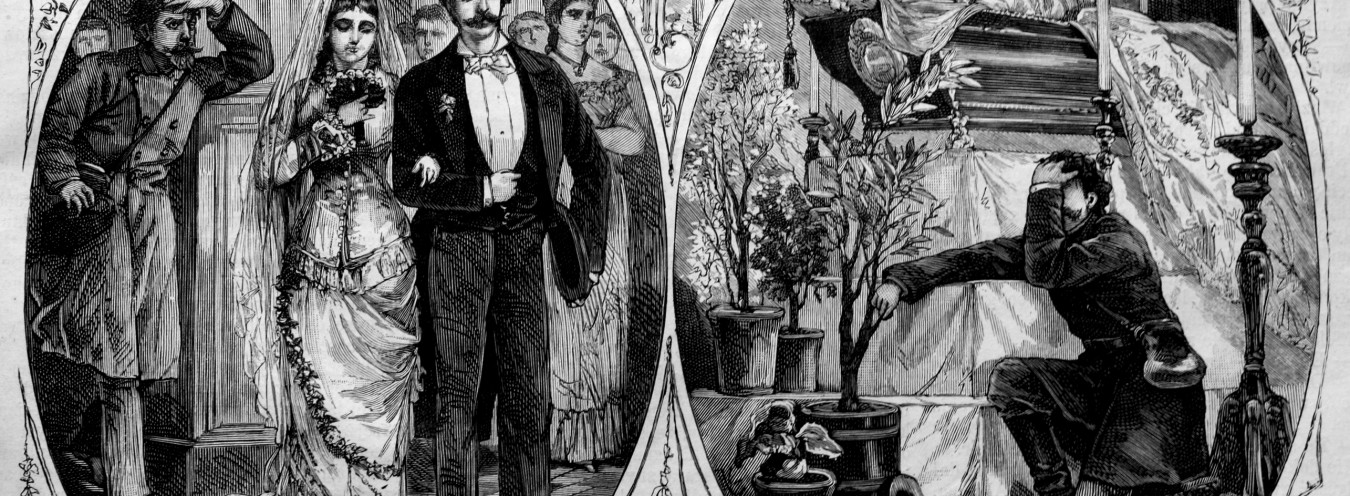

Marriage

Marriage is too important an event to enter into on the strength of feelings alone. It isn’t a poetical union between two souls, but an important event for many people and interests. (412)

These highly practical words of wisdom come from one of the characters of The Doll, Kazimierz Starski, to justify his view that he needs to marry a suitable (i.e., suitably rich) candidate for a wife. Without a substantial dowry, he claims, a man who follows his heart will be lost to [his] world. Kazimiera Wąsowska, sickened by such cynicism, tries to point out that her own motivation to enter a marriage of convenience was more complex, to which Starski replies ironically: Yet you did it, and so did grandmama, and we all do the same.

In the novel, marriage appears to be irrevocably linked to the question of money. Even those who look down on marrying for money and do not stop trying to find their soulmate cannot get over their “mercenary” marital experience (Wokulski refers to his relationship with Małgorzata Mincel as that unhappy marriage I sold myself into). The fact that financial means are needed not only to enter into, but also to liberate oneself from marital shackles does not escape even idealistic Ignacy Rzecki, who is so impressed with Helena Stawska that he would gladly matchmake her with Wokulski: Obviously there is nothing doing with her husband, if he hasn’t written for two years. Besides, what are divorces for? Why has Staś such a fortune?

However, even the characters who do not approve of the “marriage of self-interest” cannot offset it with any positive experience on their part. The Doll is a novel brimming with lonely characters: confirmed bachelors (Rzecki, Doctor Szuman), marriageable girls (Izabela Łęcka), widows and widowers (Wokulski, Kazimiera Wąsowska, Tomasz Łęcki, Duchess Zasławska, Jadwiga Misiewicz), abandoned wives (Helena Stawska). What is more, most married couples depicted in the novel are mismatched and unhappy. The reasons for this predicament are many and varied. The family of agent Wirski is unhappy due to financial problems. Maria and her husband Węgiełek are driven apart by the latter’s distrust, caused by the fact that his wife used to be a prostitute. Last but not least, the conjugal life of the separated Baron Krzeszowski and Baroness Krzeszowska should more accurately be called a “conjugal war” since both parties are so embittered they do nothing but make life unbearable for each other: He wants a divorce, but she doesn’t; she wants to dislodge him from managing her property, to which he won’t agree. She won’t let him keep horses, particularly one racehorse; and he won’t let her buy the Łęcki house, in which the Baroness lives and where she lost her daughter. Odd people! Everyone laughs at their antics. This vignette may be comical, but it does not change the problem at its core: the Krzeszowskis’ marriage was precisely the one of convenience, in which a wealthy bride was given an aristocratic title and the Baron gained money for carousing. Baron Dalski and Ewelina’s is an example of a similarly unhappy matrimonial union (ended in a scandalous divorce), which the reader may interpret as a grotesque version of a possible marriage between Wokulski and Izabela. The narrator ironically comments on Izabela’s idea of two souls with celebrated names linked in the bonds of holy matrimony, [which] would increase their income, while the source of all evil is mistakenly seen in mésalliance (finding a spouse outside one’s own social sphere). However, even for Izabela, raised as she was in the world of unrealistic expectations, illusions are very quickly dispelled once she learns a few domestic secrets of her friends. This makes her admit openly to herself: a husband in his dressing-gown, yawning in his wife’s presence, kissing her with a mouth still tainted with cigar smoke, often exclaiming ‘Oh, let me be…’ or even ‘You’re a fool!’, who makes a scene at home over a new hat but will spend his money away from home on carriages for an actress – this is not at all an attractive creature.

In Bolesław Prus’s lifetime, the tenet that genuine Christian love […] appears only after the Sacrament was being increasingly questioned. A bitter disappointment with the chosen one was often due to personality clashes, incompatibility of interests, differences in interpreting the world that stemmed from vast disparities in bringing up boys and girls as well as the traditional social roles of men and women. Families were broken up by lack of affection or cheating on partners (as done by Dalski’s fiancée and then wife). One cannot but agree with the author’s diagnosis, though it is delivered through the dubious character of Izabela Łęcka: And there is no happiness in marriage.

→ Women and Love; → Money; → Family;

Bibliografia

- D. Kałwa, Polska doby rozbiorów i międzywojenna, in Obyczaje w Polsce. Od średniowiecza do czasów współczesnych, ed. A. Chwalba, Warsaw 2006.

- A. Lisak, Miłość, kobieta i małżeństwo w XIX wieku, Warsaw 2009.