Pastimes

Theatre and opera performances, parties, concerts, lectures, receptions, and official dinners –today’s reader of The Doll may interpret these activities as entertainment, but they often do not seem to be such to the novel’s aristocratic characters. Instead of pleasurable pastimes, they were just staple elements of a certain lifestyle. In spite of appearances, the nobility do not seem to enjoy them that much. If Izabela Łęcka goes to the theatre, attends parties, walks in the Łazienki park, it is to display her beauty and fine dresses rather than for pleasure (though she sometimes relishes the company of an actor whose good looks appeal to her). More intellectually intricate and creative activities are often just a cause of ennui, performed as a tribute to snobbish sterotypes (like reading fashionable French novels in the breaks from browsing through fashion journals). The pastimes depicted by Prus do not serve diversion and amusement: instead, they allow to lead the lifestyle suitable for the class one belongs to – or wishes to belong (as is the case of the Łęckis or enriched Henryk Szlangbaum), to contract the marriage of one’s dreams, or to make “proper” social contacts. Therefore, when the protagonist is fascinated by a woman, he tries to get closer to her by adopting a similar lifestyle and is prepared to do anything just to ingratiate himself with her, including activities and behaviours that, as a man of work and danger, he basically considers to be a waste of time and money. A similar stance is taken by inventor Julian Ochocki, who thus sums up his holidays in the countryside, at Duchess Zasławska’s: I’ve wasted two months fishing, picking mushrooms, entertaining ladies and such-like nonsense. Genuine pleasure is derived, in turn, from exchanging gossip, gambling (gentlemen play cards or bet horses, ladies bet among themselves), spending money in shops, occasional horse-riding, and, last but not least, flirting – as do Kazimierz Starski or Kazimiera Wąsowska, who toys with her admirers declaring openly: I am filling up the emptiness of my life.

More conventional amusements that were popular with Warsaw’s bourgeoisie included evening theatrical performances, card games with friends, and balls. This is what Wokulski’s married life with Małgorzata Mincel looked like; he often tried to get away from these awkward domestic duties by going hunting with a forester acquaintance, reading science books, and discussing politics with Ignacy Rzecki. The old clerk was right in his diagnosis of the devastating and demoralizing impact this lifestyle had on Wokulski: In this manner the lion was slowly but surely being transformed into a tame bull.

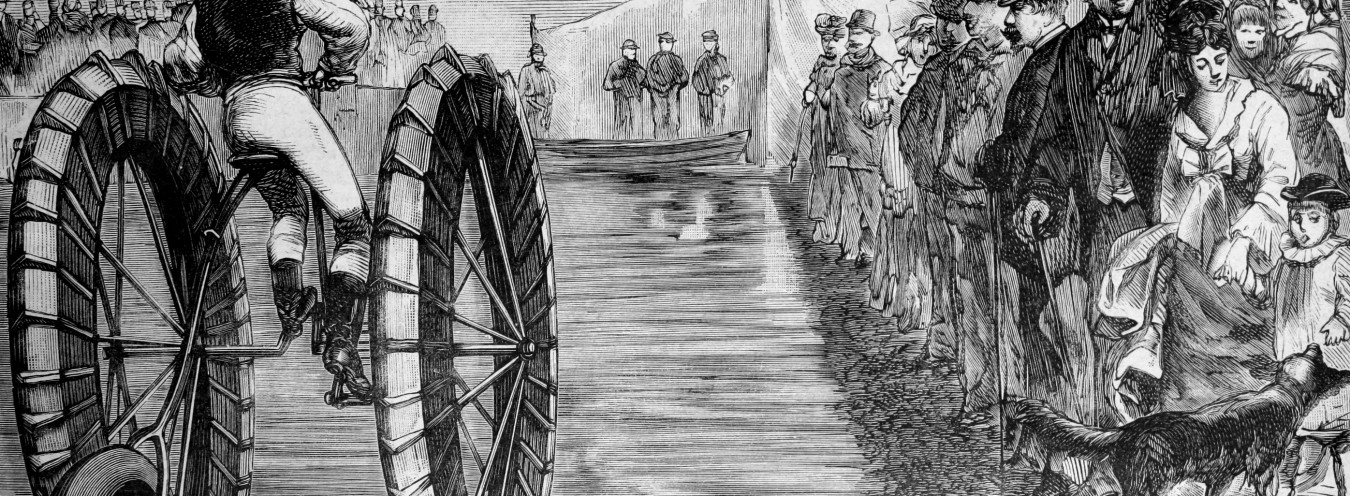

Amusing oneself in a truly satisfying way, cherishing the moment without any distracting thoughts, ambitions and plans seems to be the exclusive privilege of children and simple people. At one point, Wokulski watches a folk fair in Aleje Ujazdowskie, where several thousand Varsovians are enjoying themselves to the sound of trumpets and barrel-organs along swiftly revolving canopies, striped in different colours, where hideous monsters glowed and brightly dressed clowns, or huge dolls, were standing. People were cheering the contestants in a game that took place in the centre of this gathering: two lofty poles, up which men competing for frock-coats or cheap watches were scrambling. This sight makes Wokulski bitterly recall the long and irretrievably gone days of childhood happiness. How he used to enjoy a roll and a sausage, when he was starving! How he had imagined himself to be a famous bold warrior, as he rode on a merry-go-round! What wild intoxication he had felt flying on a swing! For Wokulski as an adult, this world of pure, unadulterated experience – just like childhood innocence – is lost forever.

→ Balls; → Gambling; → Drawing-Rooms and Salons;

Bibliografia

- D. Kałwa, Polska doby rozbiorów i międzywojenna, in Obyczaje w Polsce. Od średniowiecza do czasów współczesnych, ed. A. Chwalba, Warsaw 2006.