Sienkiewicz’s Andro-texts

In his Bible de l’humanité from 1864, Jules Michelet also devotes some space to the myth of Hercules and its break-through role in European awareness.[1] In Dziennik Literacki, in a skillful summary of Michelet’s claims, this role is described in the following way:

According to Michelet, the amazing myth of Hercules is superior to the Iliad and the Odyssey. This giant is the first one to care not only about the good of his little homeland but also about the salvation of all people, about spreading common order and common justice. What is most important, however, Hercules does not believe in destiny, does not accept it, but faces it, and fights it straight, winning everything by means of his indomitable will, hard work, and his own achievement. Michelet claims that Hercules is a hapless victim, a living complaint against the natural order of the world and lawlessness of the Gods. While Alcmene, his virtuous and faithful mother, wanted to have a lawful child, she gave birth to a bastard; he was conceived later but was born earlier due to Jupiter’s injustice. Finally, he is a slave, a slave to his older brother, weak and foul Eurystheus, a slave sold, a slave of love since, in this world, he has nothing but love.[2]

Michelet also discusses the theme of archetypical masculinity, represented by Hercules, confirmed by the experience of metaphorical and literal slavery, which is juxtaposed against effeminate Bacchus. This contrast is additionally strengthened by the opposition between the West (Hercules) and the East (Dionysus), clashing in the battle of two civilizations:

The beautiful myth of Hercules defended the old Greek lyre against the Phrygian flute and orgies. Even if he used to be Apollo’s contender, he is his friend even more. He is the hero of the West, and he pursues the eastern wild effeminate Bacchus. In Apollo, there is no element of the hardships of sorrow and death. As light, he knows no countries of darkness, and what is more, he lacks the element of work. Ethereal art and the Muses are not sufficient among the numerous heroes of work. His works are not at all ennobling in the ordinary sense of this word, but rather simple and disgusting. The heroes of Persia are also its laborers; the great liberator of Persia is Gustasp, a blacksmith, takes a hammer and an anvil; Persia did not dare to elevate such low and mean works to heroism like Greece did with Hercules.[3]

The fragments of Sienkiewicz’s prose that were cited here focus on Hercules and indicate a similar understanding of this myth – as an element of the dynamic development of the hero, who undergoes experiences that are against nature and identity, in response in order to transform to the needs of the reality, which changes in an unforeseeable manner. Similarly to journalism and literary critique, the literary works of the author of the Trilogy, which involve heroic themes, when read without search for continuity, perfectly match the crisis of masculinity that builds the dilemmatic structure of the 19th century.[4]

Thomas Carlyle wrote:

This, for reasons which it will be worthwhile sometime to inquire into, is an age that denies the existence of great men; denies the desirableness of great men. Show our critics a great man, a Luther for example, they begin to what they call “account” for him; not to worship him, but take the dimensions of him, – and bring him out to be a little kind of man! He was “the creature of the Time,” they say; the Time called him forth, the Time did everything, he nothing – but what we the little critic could have done too! This seems to me but melancholy work. The Time call forth? Alas, we have known Times call loudly enough for their great man; but not find him when they called! He was not there; Providence had not sent him; the Time, calling at its loudest, had to go down to confusion and wreck because he would not come when called.[5]

The search for a hero, clearly visible in Sienkiewicz’s works, is obviously a form of therapy, with its all limitations. In his book, Ryszard Koziołek draws attention to the “discourse of physical power,”[6] which could be a reaction against the traumas of the 19th-century history. The old ideal of knighthood was supposed to counterbalance the contemporary crisis of masculinity. But is this old ideal knighthood, in Sienkiewicz’s view, homogenous, inviolable in its structure? The Herculean theme as employed by Sienkiewicz seems to prove the contrary, and the ambiguity concerns both: aesthetics and gender.

Many years ago, Kazimierz Wyka noticed:

Sienkiewicz excels in creating heroes, but not in the sense of the super-heroes who perform heroic deeds, but the heroes in a different sense: the people whose psychology includes several fundamental and recurring features and who remain heroes in the first of the abovementioned senses, because they never stop being themselves, even in the psychologically least favorable circumstances.[7]

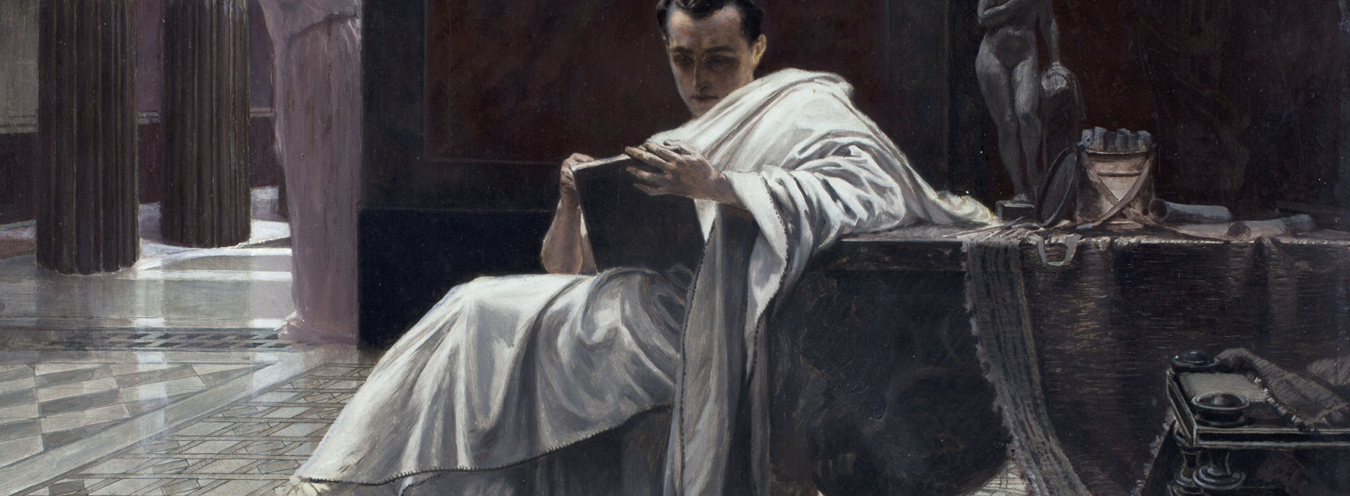

We should not stop, however, at an interpretation that focuses on the deficiencies in psychological depth and the persistent search of this depth in the places where it is clearly lacking. The passion that Sienkiewicz finds in his narration, a certain kind of pleasure derived from linguistic work become arguments encouraging us to examine his heroes in their lack of continuity, their internal contradictions concerning the restoration of their sexual roles and dimensions of heroism. When read in the perspective presented in this paper, do Sienkiewicz’s works not oscillate, to some extent, in some secret registers, towards the ideal of androgyne?[8] Is Sienkiewicz’s Hercules at Omphale’s feet not fascinated in Baudelaire’s fashion with “the heroism of modern life,” full of contradictions and aesthetic clashes? Both according to Baudelaire and Sienkiewicz (the best example could be a novel about a 19th- century Petronius, i.e. Bez dogmatu [Without Dogma]), “The painter, the true painter for whom we are looking, will be he who can snatch its epic quality from the life of today and can make us see and understand, with brush or with pencil, how great and poetic we are in our cravats and our patent-leather shoes”[9] Manly, unmanly…?

Przypisy

- See. J. Michelet, Bible de L’Humanité, Paris 1864, pp. 190–226.

- Dziennik Literacki 1865, no. 15, p. 119.

- Ibidem.

- See D. Gilmore, Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity, Yale University Press 1990; E. Badinter, XY: On Masculine Identity. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

- T. Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-worship and the Heroic in History, London 1840, p. 16.

- R. Koziołek, op. cit., p. 415.

- K. Wyka, “Sprawa Sienkiewicza” [Sienkiewicz’s case], in Szkice literackie i artystyczne [Literary and artistic sketches], Kraków 1956, vol. 1, p. 128.

- Sienkiewicz is known to have been an avid reader of Karol Libelt. See K. Libelt, System umnictwa, czyli filozofii umysłowej [The system of knowledge or mental philosophy], Poznań 1850, vol. 2, p. 82: “All of nature can be divided into two halves: male and female, and all living creatures represent this dichotomy: either masculinity or femininity. As a material atom, joining the atom of form and the atom of content, it was a transitional form for all creatures, so visible that sexuality, which links femininity (the stable type of form) and masculinity (the stable type of content) is a transitional form, that is the matrix of all kinds that creatures are divided into.”

- Ch. Baudelaire, Salon 1845, quoted in J. Mayne, Art in Paris 1845-1862: Salons and Other Exhibits Reviewed by Charles Baudelaire, London 1965, p. 32.