The Gentry

I went into the parlour, the main ornament of which was a sofa with the stuffing coming out. ‘This is what it means to be an agent,’ said the female, showing me into an equally shabby chair, ‘my husband works for gentlemen who are said to be rich, but if he didn’t work in the coal warehouse as well, and take in copying for lawyers, we should not have a morsel to eat. (327)

The fate of agent Wirski, the landowner turned into a manager of the tenement house which Wokulski buys, is a typical example of a gentry man’s biography in the historical context following the January Rising (1863). As a result of the post-uprising crackdown, and especially the enfranchisement decree which abolished socage, most landowners lost their land property and were forced to move to cities. Once they arrived, they took any job available. This de-classed group of the former landed gentry becomes the origin of some bourgeoisie and intelligentsia (it is worth noting that Wokulski himself came from the gentry).

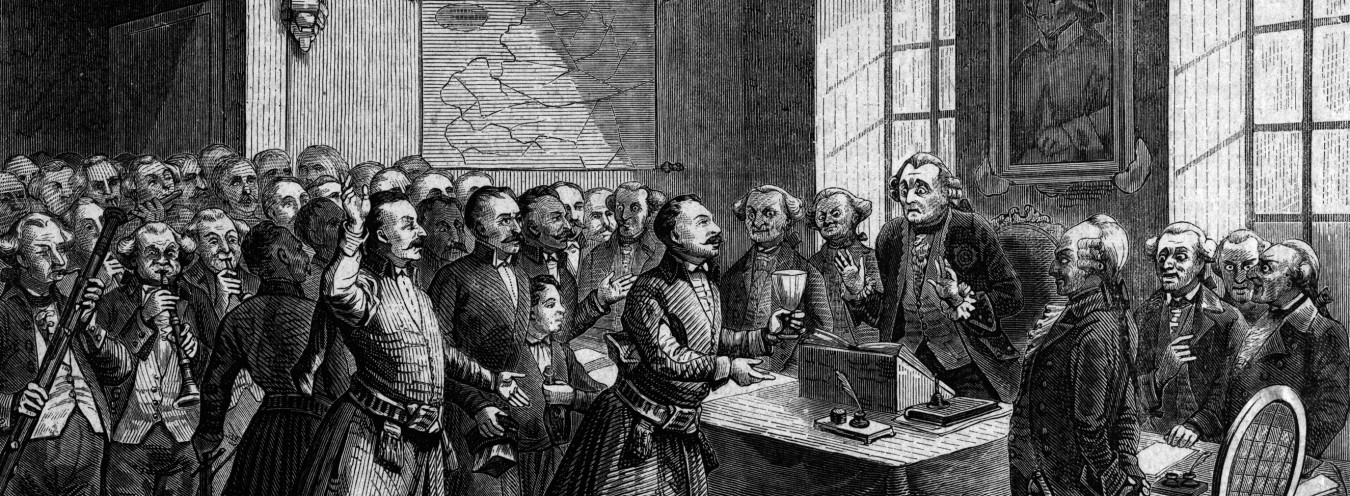

Prus records, insightfully as always, the moment in which the gentry stops being the foundation of Polish national culture – no longer determining the basic frontiers of Polishness, the norms of patriotism, no longer functioning as the driving force of the economy and culture, it turns instead into a relic of the past age. In this context, the scene in which agent Wirski recollects to Rzecki Napoleon’s triumph at Magenta becomes pregnant with symbolism: tears flowed from his eyes down to his stained frock-coat. The author managed to capture the moment of the gentry’s departure from the scene of Polish history and culture. This departure may be interpreted as a breakthrough in the culture of Poland.

→ Society;