The Press

I read that the British fleet has set out for the Dardanelles. [Klejn during a conversation in the store]. (7)

The Doll begins with a restaurant scene in which the bourgeois and the intelligentsia are equally keen on exchanging opinions about the local rumours, as they are on commenting on the global news: the way England is arming, the things Bismarck is up to, MacMahon’s deals with Ducrot, and the latest fashion. Where does the news come from? Probably from the newspapers – although the press censors would strike out anything that went against the official version of events.

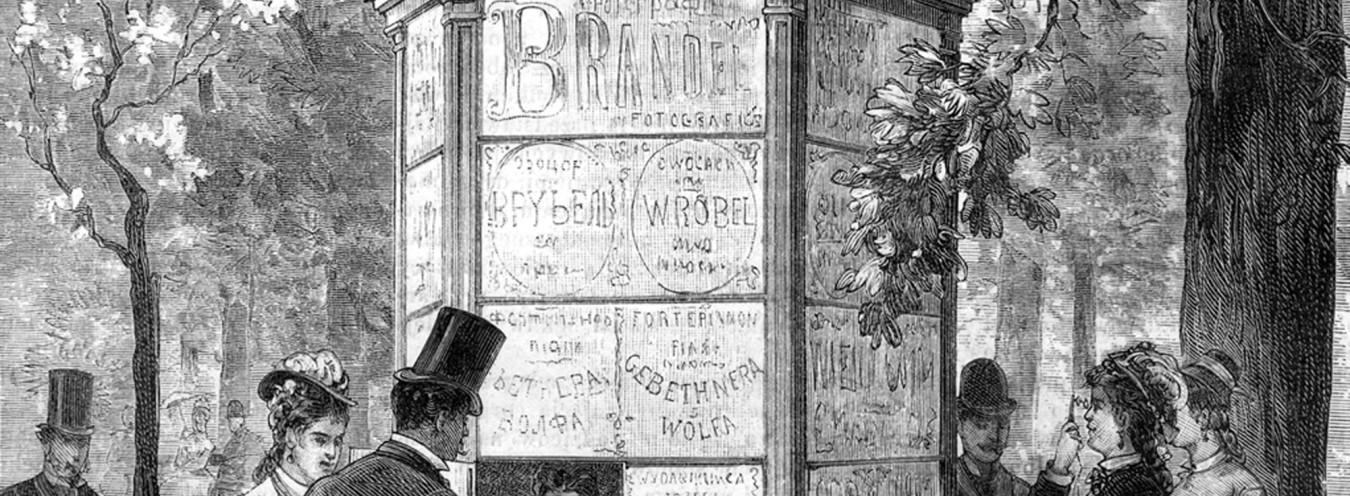

In the late nineteenth century, the press industry in Warsaw was developing rapidly, and the papers played an ever-increasing role in the city’s social and cultural life. The titles had different profiles and different target audiences. Among the newspapers addressed at the masses, the most popular title was the Kurier Warszawski, mentioned in the novel a few times, and in circulation since 1821. This daily paper owed its popularity to an expanded news section (focusing especially on local developments) as well as to its famed charades and a separate advertising section. Kurier Warszawski was also the newspaper in which, since 1874, Bolesław Prus published his famous weekly column, titled Kroniki. He also frequently collaborated with other newspapers: The Doll first appeared in instalments (between 1887 and 1889) in the Kurier Codzienny, which Prus also co-edited.

The press invented a method of propagating patriotic thought that the censors could not question: the papers reminded about historical memorabilia, monuments, and the beauty of the Polish countryside. The key proponent of this trend, Tygodnik Ilustrowany was soon followed by other illustrated magazines: Kłosy and the women-orientated Bluszcz, which also introduced modern themes such as women’s paid employment. The most famous contemporary Polish writers – Eliza Orzeszkowa, Maria Konopnicka, and Henryk Sienkiewicz – collaborated regularly with the daily papers.

Yet The Doll, nicknamed “a mirror of its age” due to its verisimilitude, only partially reflects the cultural and social influence of the press. Even the titles of the newspapers appear rarely and only incidentally. The social issues were discussed and expanded in Przegląd Tygodniowy, a weekly platform for young positivists. It is telling that this title, lauded at its time, is not mentioned in the novel at all. It is almost as if Prus made a conscious effort to gloss over the socially involved press, which influenced the patterns and ideals of civic action and citizenship.

References to the press in the novel are not vital to its plot. Wokulski mentions that the Courier often got lost in the mail and was not distributed abroad; the elderly Jew Szlangbaum reads the Courier in his modest little shop; Izabela Łęcka browses French fashion magazines. It is only in Rzecki’s life that the papers are of any serious significance: he gathers news everywhere and searches for the information that would confirm his hopes of the Napoleon’s dynasty’s return to power. The old clerk also wistfully remembers the good old years of the conservative Gazeta Warszawska edited by Józef Kenig as well as Edward Sulicki’s political articles for the Gazeta Polska. In search for exciting news, he reaches for Warszawska Gazeta Policyjna (The Warsaw Police Newspaper). Prus, however, seems to disapprove of his characters’ resorting to the press: even if they peruse them, it is not in search of the latest news. Their motivation is subjective and personal. Old Szlangbaum looks for his charades, Rzecki is of the opinion that all the latest news in the papers confuses heads, and Wokulski searches for Izabela’s name being mentioned in any context.

Such attempts to minimise the role of the press in the novel’s reality may undermine the critical opinion of The Doll as a novel-mirror of its age. In his portrayal of Warsaw and its citizens at the turn of the century, Prus seems to make his characters passive, heading for defeat – and to leave out those who aim higher, those with genuine interest in the subject matter of the press: the intellectual life, the artistic, and economic achievements. As a result, newspapers are almost absent in the novels’ world: perhaps this is so that their appearance would not clash with the depiction of the speculators who gather around Wokulski as despicable ignoramuses. On the other hand, expressions such as people say or you hear, scattered throughout the text (often uttered by Rzecki), as well as the characters of paper boys and a reporter (in an excerpt omitted from the book edition) – all these do suggest that one tended to overhear things which censors would not have allowed to be printed in papers. And that the overheard news would then serve as an inspiration for political dreams and hopes – like those still harboured by Rzecki. The shattering of those dreams corresponds in The Doll with news of an impending crisis; the clerk’s hopes for Napoleon’s dynasty and France are ruined, the trade partnership is over, Wokulski disappears, Izabela vanishes to into a convent, misery and mediocrity prevail.

→ Intelligentsia; → Rumour; → Fin de siècle;

Bibliografia

- J. Myśliński, Prasa polska w dobie popowstaniowej, w: J. Łojek, J. Myśliński, W. Władyka, Dzieje prasy polskiej, Warszawa 1988.

- C. Gajkowska, hasło Czasopiśmiennictwo literackie XIX wieku, w: Słownik literatury polskiej XIX wieku, red. J. Bachórz i A. Kowalczykowa, Wrocław 1991.