Accommodation

Mr Tomasz Łęcki, his only daughter Izabela and his cousin Flora […] rented an apartment of eight rooms near Aleje Ujazdowskie. There he had a drawing-room with three windows, his study, his daughter’s boudoir, a bedroom for himself, a bedroom for his daughter, a dining room, a room for Flora and a dressing-room, not to mention the kitchen and quarters for servants. […]

The apartment had many advantages. It was dry, warm, spacious, light. It had marble stairs, gas, electric bells and taps. Each room could be linked with the others if required, or form an entity by itself. (32)

For twenty-five years, Ignacy Rzecki had lived in a little room behind the store. (5)

The Doll invites the reader to take a look inside a number of apartments in nineteenth-century Warsaw. Prus shows us into homes of the poor, bourgeoisie, and gentry, drawing our attention to the period’s fixtures and fittings (in the case of one-room places) or the functions and description of many different rooms (within multi-room apartments). In addition, the novel contains a lot of information about the city’s sanitation and waterworks system.

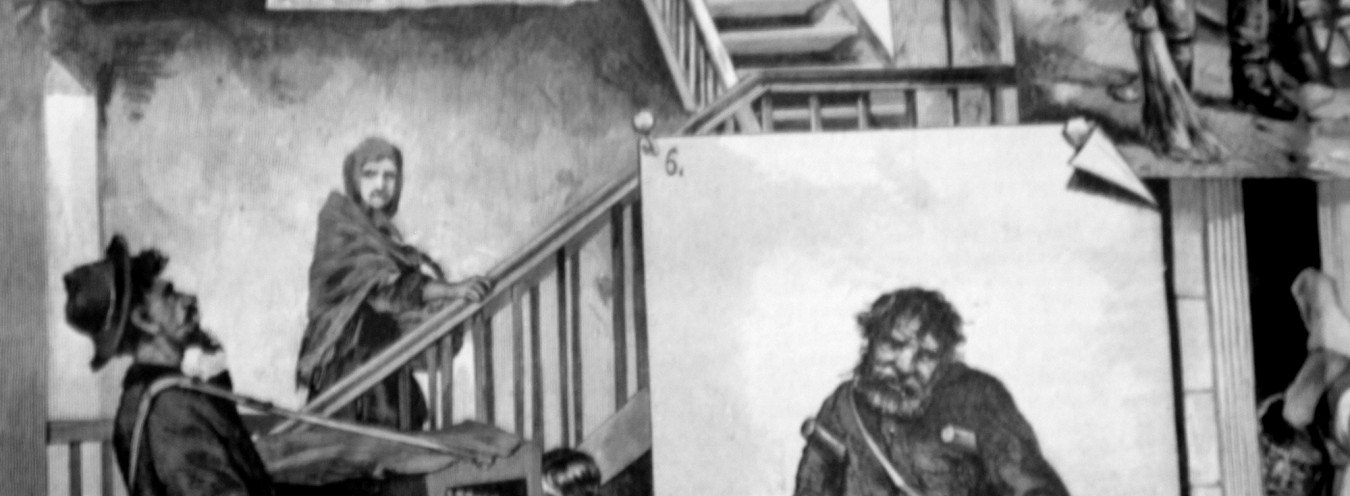

In the second half of the nineteenth century, a large part of the Polish population – not only the poorest classes – lived in one-room accommodation. Apartments of low-income tradesmen and craftsmen consisted of only one room with a kitchen, adjacent or even connected to their shops or workshops. The room could be divided with a courtain or a screen into the reception and private spaces. Rzecki’s modest flat is too cramped for this simple trick, but furnishings that can be found there (a table, a sofa and chairs) are part of a set of furniture typical for the parlour part of an apartment or a room. They are all made of the same type of wood and upholstered with the same fabric. The author’s comparisons of Rzecki’s flat and Baroness Krzeszowska’s drawing room to a grave and graveyard respectively imply that these places have long lost their stylishness. However, these descriptions can be also read as indicative of their owners’ characters. Rzecki sleeps on an iron bed with a very thin mattress, which seems ascetic compared to regular wooden divans; this type of bed was manufactured in the Warsaw metalworks from the mid- nineteenth century onwards. Rzecki’s lighting paraphernalia – a pair of brass candlesticks and steel snuffers (to cut candle wicks and prevent them from fast burning and smoking) could be commonly found in Warsaw households of that period. Apart from brass, candlesticks could also be made of tin, sheet tin, or faience, not to mention silver and silver-plated metal for more affluent families. Oil and kerosene lamps, whether hanging or standing, were still a rarity in Polish homes.

At that time, Varsovians did not seem to own many books. In The Doll, only the students’ flat is filled with a multitude of books lying on shelves, on the trunk and on the floor, and the Prince’s apartment is said to have a separate library room. Apart from that, the descriptions of Warsaw interiors do not include any mention of books, though sometimes the novel’s characters are depicted reading. The most important decorative elements are paintings of mostly religious themes, followed by landscapes and portraits of relatives, the ruling Tsar, or (as in Rzecki’s family home) particularly esteemed personages such as Napoleon, Prince Józef Poniatowski, or Tadeusz Kościuszko. As regards musical instruments, the guitar was most popular among the poorer classes. The intelligentsia considered it to be too vulgar, opting for the piano. Though expensive and thus affordable to few, the piano brought a certain prestige. There is one in Baroness Krzeszowska’s drawing room, but, draped in coverings, it does not fulfil even a representative function anymore.

Personal hygiene was maintained with the use of various basins and wooden or tin bathtubs. Varsovians usually had to fetch water from the street, since it was piped to very few houses at that time. The Łęckis’ apartment in Aleje Ujazdowskie was equipped with this modern amenity, but in their tenement house nearby, in Krucza, the conduit ended in the yard, right next to a dustheap, laundry, and probably a privy (though this facility is not mentioned by Prus). Used water was brought out of flats and laundries and poured into the gutter. People usually had their clothes washed, which allowed hundreds of poor women to earn their living. Warsaw waterworks, designed by Enrico Marconi, were installed in the 1850s only in the centre of the city: in other city regions, people had to draw poor-quality water from numerous wells dug close to their buildings. The Doll is set before William Lindley’s effective water and sewerage system was introduced and the Warsaw Water Filters in Koszykowa were put into operation.

As of 1882, approximately 18 percent of Varsovians lived in apartments of five or more rooms, which meant that they had enough space to divide according to their individual needs and habits. The most common solution was to separate the private from the public. Obviously, the hub was the drawing room, even in smaller flats; the example is Helena Stawska’s little parlour, where beautiful items and flowers create an atmosphere so appealing to Rzecki (It was a small, pearly-coloured room, with emerald-green furniture, a piano, both windows full of pink and white flowers, prizes of the Fine Arts Society on the walls, a lamp with tulip-shaped glass on the table).

In his descriptions of aristocrats’ apartments, Prus usually lists master’s studies, boudoirs, dining and drawing rooms, servants’ quarters, bedrooms, libraries, even smoking rooms (there is one in the Prince’s palace). A boudoir was an elegant room where the lady of the house could either invite and entertain guests or withdraw to take some rest, read books, and write letters; a master’s study was where the master of the house could work on new business moves or rest, reading books and newspapers.

→ Personal Hygiene; → Ir and Other Animals; → Warsaw Tenement Houses; → Sewers and Sewerage System;

Bibliografia

- E. Kowecka, Mieszkania warszawskie w XIX wieku (do 1870 r.), in Studia i materiały z historii kultury materialnej, vol. 56, Wrocław 1983.

- D. Kałwa, Polska doby rozbiorów i międzywojenna, in Obyczaje w Polsce. Od średniowiecza do czasów współczesnych, ed. A. Chwalba, Warsaw 2004.

- S. Milewski, Codzienność niegdysiejszej Warszawy, Warsaw 2010.