Sewers and Sewerage System

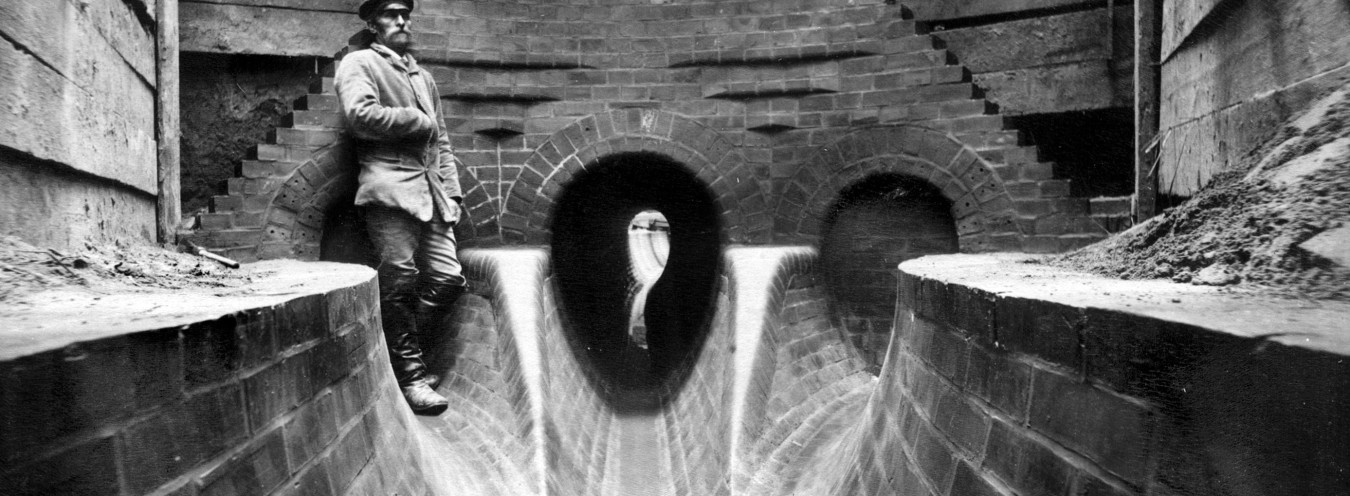

[Figure courtesy of Warsaw Public Library – Central Library of the Masovian Province]

Here, occupying several acres of space, was a hill of the most hideous garbage, stinking, almost moving under the sun, while only a few dozen yards away lay the reservoirs from which Warsaw drank. (74–75)

Warsaw was a city of contrasts. The elegant, glamorous areas of Krakowskie Przedmieście and Aleje Ujazdowskie neighboured the industrial Powiśle, where rubbish was deposited in order to regulate the flow of the Vistula. Walking towards the river, Wokulski saw miserable housing, mostly inhabited by the poor; he saw an area of destitution, disease, and moral degradation. Still, he daydreamed, A boulevard here, drains and water from the hill-top – several thousand people could be saved from death, and tens of thousands from diseases.

There was a shortage of drinking water in Warsaw due to a lack of waterworks. Frequent water shortages in the summer were a serious threat, and they caused increased mortality among the city’s inhabitants. Although a waterworks system – designed by renowned architect Henry Marconi and located at Dobra Street – had been in use since the year 1855, its supplies covered only a fraction of the demand (in 1876, 362 houses used the waterworks). In the novel, there is no running water, for example, in Rzecki’s room, which meant he had to carry it upstairs for drinking and bathing.

In 1877, the city entered into a contract with engineer William Lindley, who would design and construct a new waterworks and sewerage system. The construction, however, did not commence until 1882. Until then, most people took their water from municipal wells, which were highly contaminated.

The sewage was directed into the Vistula River. Together with rainwater, it flowed down the deep, stinking gutters onto the streets. In the summer, the gutter stench was unbearable, and they contributed to the spread of diseases. In the winter, the gutter water would freeze over and, when it thawed, it flooded the streets.

The pollution in Warsaw was compounded by the cesspools, which at that time were built out of brick. They were emptied every few weeks by hermetic cisterns, 1.87 cubic metres in volume. These were filled with fluid waste within minutes with the use of a pump and pipe. The cisterns, however, frequently leaked, and thus they polluted air and groundwater.

Communal toilets were usually built in the yards of tenement houses. They were small wooden constructions, cleaned by the janitor once a month. Some houses placed improvised toilets in the stairwells or under the stairs. The well-to-do houses had separate toilets, furnished with an armchair of a kind, with an upholstered back and armrests. The toilet pedestal was used instead of legs, and the seat had a round hole, underneath which a ceramic dish would be placed.

Water closets were a hygienic novelty in Warsaw at that time. Produced by Karol Minter’s company, they were designed as hermetic and the waste was flushed down with water. Such closets, however, could only be installed in buildings connected to the sewerage system.

For those whose dwellings lacked such connection, special facilities called “baths” were designed. They were equipped with bathtubs and showers, and offered a wide range of mineral baths alongside a selection of waters from reputed European spa locations.

→ Personal Hygiene; → Accommodation;

Bibliografia

- M. Gajewski, Urządzenia komunalne Warszawy, zarys historyczny, Warsaw 1979.

- S. Milewski, Codzienność niegdysiejszej Warszawy, Warsaw 2010.