Images within images

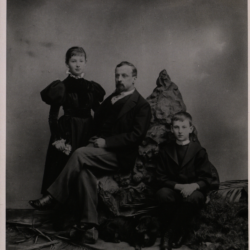

The portraits of Sienkiewicz himself were published in the December 22 Tygodnik Ilustrowany issue (no. 9). There was a painting by Kazimierz Pochwalski on the first page. Secondly, the magazine printed the reproduction of Henryk Sienkiewicz w różnych epokach życia (Henryk Sienkiewicz in different stages of life), which consisted of eight photographic portraits of the writer. The cycle began with Sienkiewicz’s secondary-school years (1863), portrayed him respectively in 1869, 1872, 1878, 1880, 1883, 1899, and closed with the most up-to-date image – a photograph by Jan Mieczkowski. This photograph, taken in the jubilee year, showed Sienkiewicz in the foreground, with the Warsaw cityscape in the background, and was accompanied by the Roman numeral XXV related with to the 25th Jubilee. What did this combination of images communicate? Did it imply that Sienkiewicz was young once, or that he graduated in Warsaw? Or maybe the portrait selection was a statement meaning that Sienkiewicz had always been one of us? Maybe it told the story of the writer’s maturity, of him aging gradually, as documented in a lifelong snapshot experiment? Maybe it communicated the fact that such form of documentation was technologically possible, and that Sienkiewicz, born in the 1840s, was one of the first to have an almost complete series of portraits? In addition to this photographic cycle, Tygodnik Ilustrowany printed a portrait of Sienkiewicz based on Aleksander Karol’s photograph, a photograph of the writer’s bronze bust carved by Stanisław Roman Lewandowski, Julius Mien’s photograph of Sienkiewicz in Zakopane (accompanied by children and a dachshund),[1] and finally, a portrait in pencil drawn by Witkiewicz.[2]

Kazimierz Pochwalski, whom I have already mentioned, made a number of Sienkiewicz’s portraits. The first two were finished when Pochwalski and Sienkiewicz were traveling together in 1886 to the Middle East, next ones were created in 1889-1890 (later, Pochwalski co-authored also Album jubileuszowy [The jubilee album] published in 1898, in which the first image of Sienkiewicz was Pochwalski’s 1890 work). I am especially interested in Pochwalski’s painting, which is presently the most well-known image of Sienkiewicz, and which was also iconic in the late 19th century. Due to the popularity of this image, I would like to concentrate on its social circulation as well as the relationship between the artwork and the writer. Pochwalski began working on the portrait in the summer of 1889 in Kraków. Sienkiewicz describes it as follows: “Yesterday I visited Pochw[alski], who began to work on the portrait, made a sketch, and started to paint. I don’t know what will happen next, but now there is no likeness. A broad head, short nose, walrus mustache – no likeness at all. […] It’s going to be finished soon.”[3] This work, however, was not quickly finished, as Pochwalski and Sienkiewicz were soon preoccupied with managing their travels around Europe. Thus, the model and the artist returned to their work after nearly a year. Next year in June, Sienkiewicz wrote to Janczewska, slightly disputing the mocking tone of her earlier comments:

My portrait is going to be finished by Thursday – and it will be very good: a bit bigger than reality, that’s why my body and my face seemed enormous, but this enormity disappears in the process of corrections. It shall disappear even more due to the box frames, and the way the portrait will be hanged. Its style is, in general, very serious.[4]

This painting appears twice in the 10th jubilee issue of the Tygodnik Ilustrowany: on the cover and on the photograph depicting a wall in the writer’s apartment. The artwork is also described and interpreted by Hoesick:

The wall above the ottoman is almost completely covered by two portraits painted by Pochwalski: Sienkiewicz’s famous portrait of 1890, undoubtedly the best of all his portraits, and the portrait of the late Mrs. Sienkiewicz […].

In the portrait one can see Sienkiewicz sitting in a stylish armchair and looking at the viewer, his face firm and true, with a dark olive complexion (as if he came from the Mediterranean), and sporting a short Spanish-style beard – a truly manly face with regular, noble features, an aquiline nose, dark, expressive eyes full of melancholy. When one notices Sienkiewicz’s pensive mood, perfectly rendered by the painter and generally characteristic for the writer, one is automatically reminded of Lorenzo Il Pensieroso, whose reverie is similarly striking.

At the same time, looking at this portrait, painted while Sienkiewicz was writing Without Dogma, one is of the impression that this is a meaningful portrait of a writer who enriched the world with the creation of Płoszowski – the Werther and the Hamlet of the late 19th century.[5]

What is especially noticeable in this description is the aspect which was also emphasized in the writer’s letter to Jadwiga Janczewska: namely, the portrait is a “talking image,” which means that it tells stories embedded in the exact time and space. Most importantly, however, it is an accurate representation of Sienkiewicz in 1890 – in the period when he was writing his fin de siècle novel, and the portrait reflects the essence of this literary work (together with further references: Leon Płoszowski, the protagonist of Without Dogma (Bez Dogmatu), who is also the author’s reflection, summons the iconic heroes of Wolfgang Goethe and William Shakespeare). There is even more to this description: Sienkiewicz’s countenance resembles Michelangelo’s sculpture of the Duke of Urbino but also reminds the viewer of a patrician – maybe even of Gaius Petronius Arbiter, casting a melancholic glance into the dusk of the world as he knows it. Sienkiewicz’s image is characterized by all the traits that were commonly associated with the writer: “manly” looks, dark eyes full of melancholy (caused by his first wife’s death or by the state of the nation), facial features noble and sharp (brought out by a Spanish-style beard), and a slight tinge of exoticism, which amounted to a darker complexion, often associated with Sienkiewicz’s Tartar ancestors.

Therefore, the image of Sienkiewicz, which was already reprinted twice, was once again described by Hoesick. This was, however, not the last time:

Standing in front of the 1890 portrait and looking at the true Sienkiewicz, one can notice only a slight change: within the scope of ten years, the author has grown quite a lot of grey hair. The brown-haired man has become grizzled.[6]

The fourth image of Sienkiewicz is revealed – the writer looks only slightly different, his hair is slowly going grey. Hoesick repeats the gesture of the mentioned tableau, comparing the writer’s appearance from before a decade to the one that is revealed to him.

An apt reader, who has navigated through a number of paragraphs full of various images of the jubilee, turns the page again only to see – for the fifth time – the same clouded countenance, the same hands crossed on the backrest of a chair, the familiar pleats in the jacket, crinkles in the waistcoat. This is the drawing entitled Sienkiewicz u siebie (Sienkiewicz at home): ten years after Pochwalski portrayed him, Sienkiewicz sits in exactly the same pose in his apartment on Wspólna Street. This famous image of Sienkiewicz is an almost identical reproduction of the 1890 portrait – only the perspective is slightly different. Ferdynand Hoesick prepared the reader for the proper reception of this image with his detailed description, which also supports his opinion of Pochwalski’s painting being “undoubtedly the best of all his portraits,” or, in other words, the image that should come to our minds whenever we think of Sienkiewicz. Guns and hunting trophies are located in the background, an ashtray and some quills on the desk, the Warsaw cityscape is behind the closed window drapes. The portrait of Sienkiewicz’s wife hangs on the opposite wall (painted by Kazimierz Pochwalski in 1886[7]). Her bust hangs over the writer’s right arm as if she were his guardian angel. The 1890 portrait made by Pochwalski is outside the frame. Sienkiewicz could catch a glimpse of it with his right eye, and properly assume his pose opting for an adequately cloudy countenance. He could place his hand on the backrest in the right manner, emphasizing the continuity of his existence, as well as the passing of time this way.

Przypisy

- All of them are to be found in issue no. 10.

- See Tygodnik Ilustrowany, no. 51.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 2, part 2, letter no. 173 (July 4, 1889), p. 98; trans. K. F.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 2, part 2, letter no. 233 (June 22, 1890), p. 285; trans. K. F.

- F. Hoesick, op. cit., p. 188; trans. K. F.

- Op. cit., p. 188; trans. K. F.

- Sienkiewicz mentioned it in his letter to Janczewska. See Listy [Letters], vol. 2, part 1, letter no. 10, p. 140, 31.07.1886.