Sienkiewicz as a double spectacle

Sienkiewicz, present in Stanisławów merely as a statue, personally visited the Wielki Theater in Warsaw. This had been a long day, and the body of the not-so-young writer must have already been tired. Nevertheless, he stood in front of the gathered audience, in one more tableau vivant, constituting the center around which a symmetrical composition of admirers was grouped. It was a metonymic performance of Polishness, the national pars pro toto, which Poles had constructed out of themselves (and the allegories of certain values), with Sienkiewicz playing the main, though silent, role.

The spectators dressed in their anniversary costumes were holding loud conversations before the curtain went up. The roar of voices resembled the roar of a rough sea. This loudness, the smiles on people’s faces, their eyes shining – all indicated excitement. Everyone became silent when the Jubilee appeared in his box decorated with flowers…

Everyone looked at him…

And he, solemn as always, with a melancholic look on his face – stared into the room… He almost cried… What surrounded him was Respect, Adoration, and Love. They were all sitting in the chairs, looking out of their boxes, leaning on the railings, soaring like swallows…

The Poet-Jubilee saw all these emotions on the people’s faces. As these feelings were all aimed at him, he stood thrilled, with a pounding heart. The applause was really long… Spectators kept clapping to the rhythm of their hearts beating for the great Poet…[1]

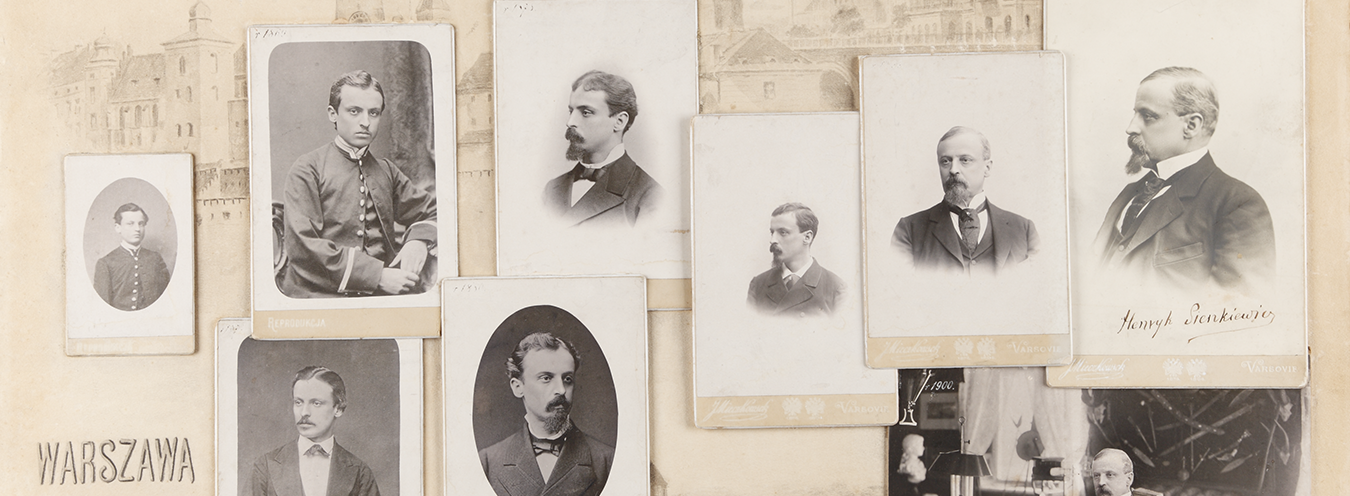

Even though Sienkiewicz’s cloudy countenance visible in the central box of the Wielki Theater may suggest otherwise, it is possible to argue that the writer preferred to shape his image in visual self-narratives rather than in words. In a well-known correspondence with Stefan Demby (who worked on Sienkiewicz’s bibliography), which was exchanged just before the jubilee, that is in 1899 and 1900, Sienkiewicz summarized his life for the first and the last time, revealing it to the readers’ eyes. His biographical note was very brief, limited to a few dozen sentences, which are full of mistakes (according to the editors). Sienkiewicz was, however, pressing for the publication of his portrait (a photogravure) in the edition of Humoreski z teki Worszyłły (Humorous Sketches from Woroszyłło’s Portfolio) and Selim Mirza.[2] He also used to sign letters with a self-portrait – for example, a caricature of himself endowed with a prominent belly.[3] Of course, Sienkiewicz and his admirers created a visual persona of the writer, but these representations soon acquired a life of their own. This involves both an inertia that determined the circulation of the writer’s portraits, distributed by both the writer and the exponents of his works, but also the very logic of images, concerning their functioning, will, and biographies. This is why the methodological basis of the following paragraphs is related, first of all, to the role of social circulation of cultural texts, in this case, images, whose significance was emphasized by Stefan Żołkiewski.[4] At the same time, I use tools and methods introduced by specialists in the field of visual culture, which allow me to explain the active role of visual images.

Since his early years, Sienkiewicz was preoccupied with images. In a letter to Ignacy Baliński, he stated:

The third book that made a grand impression on me was an illustrated book on Napoleon’s life.[5] From the moment I had finished it, I dreamt of becoming a great leader of a nation ruling Europe. This dream accompanied me during my entire childhood and the early period of my youth.[6]

It’s an important statement: visualizing the life story of a certain individual shaped Sienkiewicz’s aesthetic sensitivity. Later, Sienkiewicz was known as sensitive to the beauty of adults and adolescents of both sexes: proof can be found in early correspondence with Konrad Dobrski and other friends made by Sienkiewicz during the summer holiday of 1886. In these letters, Sienkiewicz included photograph-based drawings of himself and his colleagues, as well as reported in lively discussions held on styles and aesthetics, especially the ones related with the woman whom Dobrski adored. Sienkiewicz rushed his addressees: “Send the photograph quickly, I’m dying,”[7]“I need this photograph with all my heart.”[8] His vivid imagination was full of images even at the time of the first literary endeavors, but his everyday existence was full of images, too. Sienkiewicz enjoyed posing for pictures, collecting, and sending them. He gladly commissioned photographic processing and kept the photographs in diaries and books. He carried them hidden among personal belongings, treating them as valuable companions of his distant travels.

Sienkiewicz was very focused upon his own body, and this phenomenon is especially vivid when the writer’s awareness of even the tiniest ailments is considered. This trait has even been attributed to Sienkiewicz’s alleged hypochondria.[9] Having insight into what is happening within the body is often related with a propensity towards imagining the body itself – and this process is clearly visible in the letters sent by Sienkiewicz to his closest friends, in which the writer provides lengthy descriptions of his physical suffering succeeded by the descriptions of his portraits. For example, in the seven known letters to Karol Benni, Sienkiewicz discusses the oil paintings of himself and his wife (as well as the transportation of the artworks to Oblęgorek); he often mentions photographs and the art of photography as well as other visual representations.[10] The correspondence with Jadwiga Janczewska,[11] which I have already mentioned at the beginning of this paper, can serve as an exquisite source of self-references and meta-commentaries. One should also remember about the letters gladly exchanged and friendships made with visual artists responsible for Sienkiewicz’s portraits: Józef Chełmoński, Jan Styka, Stanisław Witkiewicz, Kazimierz Pochwalski, and Józef Deskur.

As I have already stated, the images of Sienkiewicz are not limited to printed representations. Special editions of the Warsaw press also mention medals or other accessories, whose quality – incidentally – left a lot to be desired: “some shops with jewelry sold key rings with Sienkiewicz’s portrait – which, however, was not one of the best.”[12] Interestingly, people and items related to Sienkiewicz tended to be portrayed, too. There are known reprints of the effigies of individuals responsible for theatrical adaptations of Sienkiewicz’s works as well as for the translations of these works into English, Italian, Portuguese, and German. Yet another form of paying metonymic homage to the writer in question was the circulation of the illustrations accompanying his novels as well as the distribution of artworks based on Sienkiewicz’s literature. At the turn of the 20th century, such images were widespread and sometimes even exhibited. The visual career of artworks related to Quo Vadis is worth a separate paper, or even a monograph: the process of the social circulation of the novel’s editions was accompanied by paintings, sketches, exhibitions, slideshows, theatre plays, operas, tableaux vivants, and cinematographic images. Album jubileuszowe Henryka Sienkiewicza: główniejsze sceny i postacie z powieści i nowel Sienkiewicza w dwudziestu ilustracjach[13] (The jubilee album of Henryk Sienkiewicz: Major events and protagonists of his novels in twenty illustrations) published in 1898 (the year for which the “first” Henryk Sienkiewicz jubilee was planned) was a special edition, which consisted of nineteen illustrations made by the best Polish artists of that time. The illustrations depicted the protagonists of Sienkiewicz’s novels and novellas as well as selected scenes from his works (which could later be used to create tableaux vivants), all complemented with relevant quotes.

Other sources worth microhistorical analysis are the issues of the Tygodnik Ilustrowany magazine that were partially or fully devoted to Sienkiewicz’s jubilee: issue 10 and 11 (March 1900), 51 and 52 (December 1900). These issues are replete with visual images of places which Sienkiewicz used to visit: the guest house in Zakopane, the villa near Paris, the park in Saint-Maur, the landscapes of the Marne river (“this is greatly satisfying: to row a boat on the Marne, early in the morning”[14]– Sienkiewicz stated) or the surroundings of Perros-Guirec in Brittany (with the castle in Ploumanac’h portrayed three times). The largest prints were devoted to the writer’s private properties (his mansion in Oblęgorek and the study in his Warsaw apartment at Wspólna 24) as well as to Wola Okrzejska – Sienkiewicz’s place of birth (these prints represented his childhood home, the manor outbuilding, the village, and the church).

Przypisy

- “Jubileusz H. Sienkiewicza” [Henryk Sienkiewicz’s jubilee], Kurier Poranny December 23, 1900, no. 354, p. 7; trans. K. F.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 1, part 1, pp. 197–201.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 2, part 2, p. 19 (caricature as the illustration no. 18 to be found on the back of page 96).

- Following Stefan Żółkiewski’s lead, I assume that a study of a cultural text cannot be conducted without considering its social circulation among recipients; see S. Żółkiewski, Wiedza o kulturze literackiej. Główne pojęcia [Literary culture: Key concepts], Warsaw 1985, pp. 244–52; S. Żółkiewski, Kultura. Socjologia. Semiotyka literacka. Studia [Culture. Sociology. Semiotics of literature. Studies], Warsaw 1979, pp. 408–415.

- According to the editors, the book in question was an anonymous work entitled Życie Napoleona podług najlepszych źródeł z rycinami na stali rytymi z oryginalnych obrazów najsławniejszych malarzy francuskich [The life of Napoleon with engravings based on works by the finest French painters], S.H. Merzbach, Warsaw 1841, vol. 1 and vol. 2.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 1, part 1, p. 37; trans. K. F; emphasis P. K.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 1, part 1, p. 323; trans. K. F.

- Op. cit., p. 325; trans. K. F.

- See B. Szwargot, “Sienkiewicz prywatnie i oficjalnie” [Sienkiewicz: Formally and informally], Sztuka Edycji 2016, vol. 2, p. 137.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 1, part 1, pp. 75–8.

- For instance, “I consider myself as much more handsome,” H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 2, part 2, p. 55; trans. K. F.

- “Jubileusz H. Sienkiewicza” [The jubilee of H. Sienkiewicz], Kurier Poranny, 23.12.1900, no. 354, p. 9; trans. K. F.

- Album jubileuszowe Henryka Sienkiewicza : główniejsze sceny i postacie z powieści i nowel Sienkiewicza w dwudziestu ilustracjach: Józefa Brandta, Józefa Chełmońskiego, Antoniego Kamieńskiego, Juliusza Kossaka, Wilhelma Kotarbińskiego, Kazimierza Pochwalskiego, Jana Rosena, Henryka Siemiradzkiego, Piotra Stachiewicza i Wincentego Wodzinowskiego [The jubilee album of Henryk Sienkiewicz: Major events and protagonists of his novels in twenty illustrations by Józef Brandt, Józef Chełmoński, Antoni Kamieński, Juliusz Kossak, Wilhelm Kotarbiński, Kazimierz Pochwalski, Jan Rosen, Henryk Siemiradzki, Piotr Stachiewicz and Wincent Wodzinowski], G. Gebethner i S-ka, Warsaw–Kraków 1898.

- F. Hoesick, “U Henryka Sienkiewicza” [Visiting Henryk Sienkiewicz], Tygodnik Ilustrowany, March 10 (February 26), 1900, no. 10, p. 190; trans. K. F.