Sienkiewicz: Living images, living gestures

In his analysis of film images, Giorgio Agamben states that such images are “neither poses éternelles (such as the forms of the classical age) nor coupes immobiles of movement, but rather coupes mobiles,” which allows him for the discussion of Gilles Deleuze’s images-mouvement concept. Agamben argues that:

It is necessary to extend Deleuze’s argument and show how it relates to the status of the image in general within modernity. This implies, however, that the mythical rigidity of the image has been broken and that here, properly speaking, there are no images but only gestures. Every image, in fact, is animated by an antinomic polarity: on the one hand, images are the reification and obliteration of a gesture (it is the imago as death mask or as symbol); on the other hand, they preserve the dynamis intact (as in Muybridge’s snapshots or in any sports photograph).[1]

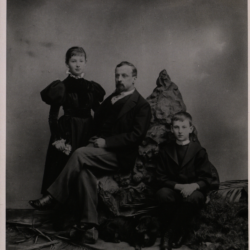

The image of Sienkiewicz, which grows out of Pochwalski’s paintings and is supplemented by the active performance of the writer, is multiplied and ceaselessly modified thanks to reproductions and minor changes in perspective. By employing Agamben’s argument in my discussion, I can argue that this plastic image becomes a reference to the development of cinematic techniques, or to the medium which operates in live, moving pictures. Thus, the Tygodnik Ilustrowany magazine offers its readers a screening of a film about Sienkiewicz – a film, which has never been made.

The notions of “living pictures” or “moving images,” stemming from the 19th century, are associated both with cinematography and an outdated form of performance – the tableau vivant, in which gestures are immobile, and yet dynamic. Therefore, the living picture of Sienkiewicz is revealed to the reader-viewer, as if the Stanisławów Apotheosis was still taking place. As Agamben notes, the modern image works in two distinct manners: “the former corresponds to the recollection seized by voluntary memory, while the latter corresponds to the image flashing in the epiphany of involuntary memory. And while the former lives in magical isolation, the latter always refers beyond itself to a whole of which it is a part.”[2] Thus, there is Sienkiewicz immersed in his past (in the years 1890 and 1900), but also Sienkiewicz encountered in the dynamis sphere, present in the living act-gesture, in which he becomes a huge, national Polish imaginarium – the one which he himself co-created, referring “beyond himself to a whole of which he is a part.”