Gambling

What a terrible position, to be sure! For a month they had been getting into debt with their butler, and for two weeks her father had been winning money at cards for his day-to-day expenses. (53)

When Bolesław Prus was writing The Doll, the Polish word for gambling, hazard (from French: hasard – “chance,” “coincidence”), meant taking a risk, leaving things to chance, displaying a daring audacity. Hence, gambling games were defined in Orgelbrand’s Universal Encyclopaedia as activities that put at stake a large sum of money or the entire property. This could also apply to business as conducted by Stanisław Wokulski, who earned a fortune on military supplies amidst bullets, knives and typhus and can now boast: High stakes?… nearly every month I risked my entire fortune, and my life every day.

Apart from the risky financial decisions of the protagonist, the novel depicts more traditional forms of gambling, mostly card games. Piquet and whist (a forerunner of the auction bridge and the bridge itself) are regularly played by Tomasz Łęcki. Baron Krzeszowski plays cards – or rather, loses at cards – every night. While visiting the Baron at his home, Wokulski notices two card tables, one with a broken leg and the other with a thickly bescribbled cloth, as well as two candlesticks with the stumps of wax candles. Mr Maruszewicz, a friend of the Krzeszowskis, who resorts to fraud and forging signatures on receipts in order to pay off his debts, is another compulsive gambler. From time to time, he plays billiards as well (pool tables could be commonly found in cafés). Towards the end of the century, billiards was officially banned by the police. Wagering was a singular form of gambling, popular even among high-society ladies (for example, Izabela Łęcka makes a bet with her aunt Countess Karolowa and wins a sapphire bracelet off of her). However, the most patent example of gambling are horse races, called the play of gentlefolk in The Doll.

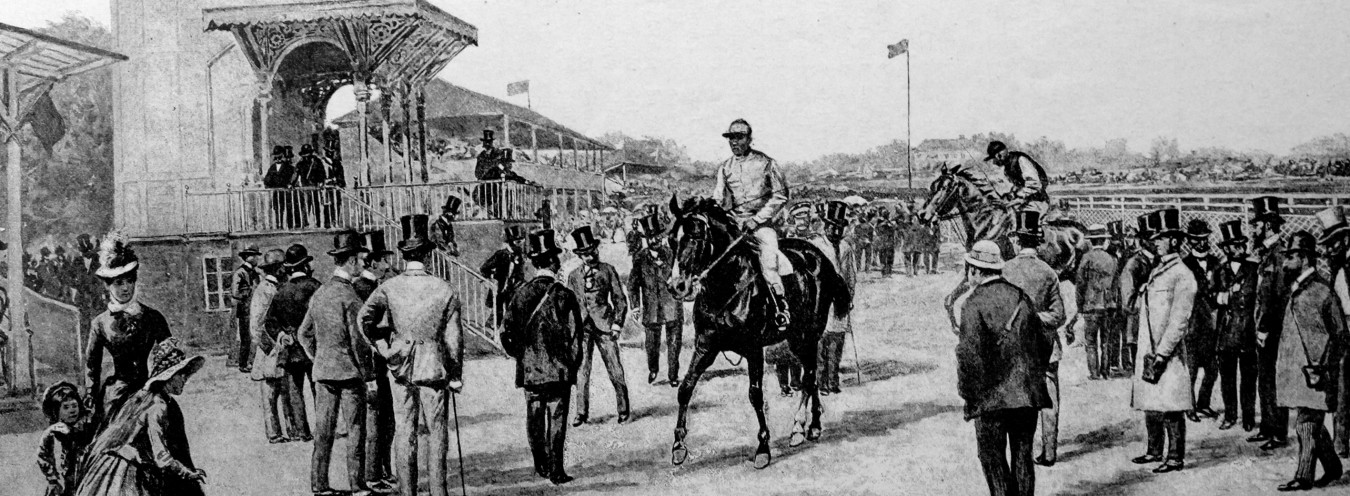

Horse racing had a long tradition in Warsaw. The Horse Racing and Livestock Exhibition Society was established in 1841. The annual contribution amounted to 50 roubles, and a single entrance ticket cost 10 roubles, which made the sport accessible only to the affluent. The members of the Society were unfavourably dubbed “horse aristocracy” and looked upon with dislike – also because of the fact that the Mokotów race-course constituted one of the few places where Poles rubbed shoulders with Russians (another “shared ground,” the theatre, took over completely when the race-course closed in 1887).

The racing season started in late spring or early summer; in 1878, when the action of the novel begins, it was inaugurated in the first days of June. This made it possible for the ladies to display their summer wardrobe in open carriages. Spectator stands were rickety and decrepit, which makes the dejected Wokulski’s imagination conjure up a gloomy vision: it seemed to him that every night, on these rotting benches, dead bankrupts, remorseful coquettes, all kinds of idlers and wastrels took their seats, having been expelled from Hell, and that by the sorrowful light of the stars, they watched the races of skeleton horses who had perished on this course. It seemed to him that even at this moment he could see mouldering garments and smell the stench of decay.

In one of his weekly press columns Kroniki, Bolesław Prus made an acerbic comment: Warsaw must be one of the most musical places in the world. Everyone plays: cooks and watchmen play a poor man’s roulette, the intelligentsia play whist, the middle class play lottery, sportsmen play sports sweepstake, financiers – the rouble exchange rate, guttersnipes – buttons. We have already recognised the fact that money is tantamount to man’s dignity and constitutes the soul of the society; but out of all the paths that lead to Mammon, we have so far discovered but one: gambling games. However, it should be noted here that the author of The Doll himself was buying lottery tickets for years in the hope of winning – and starting his own newspaper.

→ Russians in Warsaw; → Pastimes;

Bibliografia

- Encyklopedyja powszechna S. Orgelbranda, vol. 11, Warsaw 1862.

- S. Milewski, Ciemne sprawy dawnych warszawiaków, Warsaw 1981.

- A. Tuszyńska, Rosjanie w Warszawie, Warsaw 1992.