Poles in Siberia

He only breathed freely when he reached Siberia. There he had been able to work, had gained the recognition and friendship of Czerski, Czekanowski, Dybowski. He returned to Poland almost a scholar. (69)

Historically, Stanisław Wokulski belonged to the multi-thousand throng of Polish exiles to Siberia, participants of the January Rising (1863–64). Scholars estimate that in the years 1863–65 between 18,000 and 20,000 people were exiled, among these about 4,000 sentenced to penal servitude. Many were sent to Irkutsk and its surroundings – the destination of Wokulski’s exile. The exiles from the 1840s included Henryk Wokulski, arrested in 1844 and transferred east of Lake Baikal for an attempted assassination of Emperor Nicholas I. He worked as a candle-maker and returned to Poland in the 1850s. It is possible that Prus learnt about him from Agaton Giller’s Opisanie Zabajkalskiej krainy w Syberii (A Description of Eastern Siberia), yet there is no hard evidence that the writer borrowed the protagonist’s name from this volume.

Among other minor and major characters, two Poles of Jewish origins – doctor Shuman and Henryk Szlangbaum – also have insurrectory and exile episodes in their pasts, yet there is little information about their lives in Siberia. They are the only returned exiles that Wokulski keeps in touch with. We know that some of the exiles are critical about his business activities and the way that he made fortune during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78): but there were also some who turned away their heads with obvious dislike. Among them he noticed two acquaintances from Irkutsk, which impressed him in a disagreeable manner. Significantly, in the first edition, the words “from Irkutsk,” along with other references to Wokulski’s exile, were deleted by the censorship.

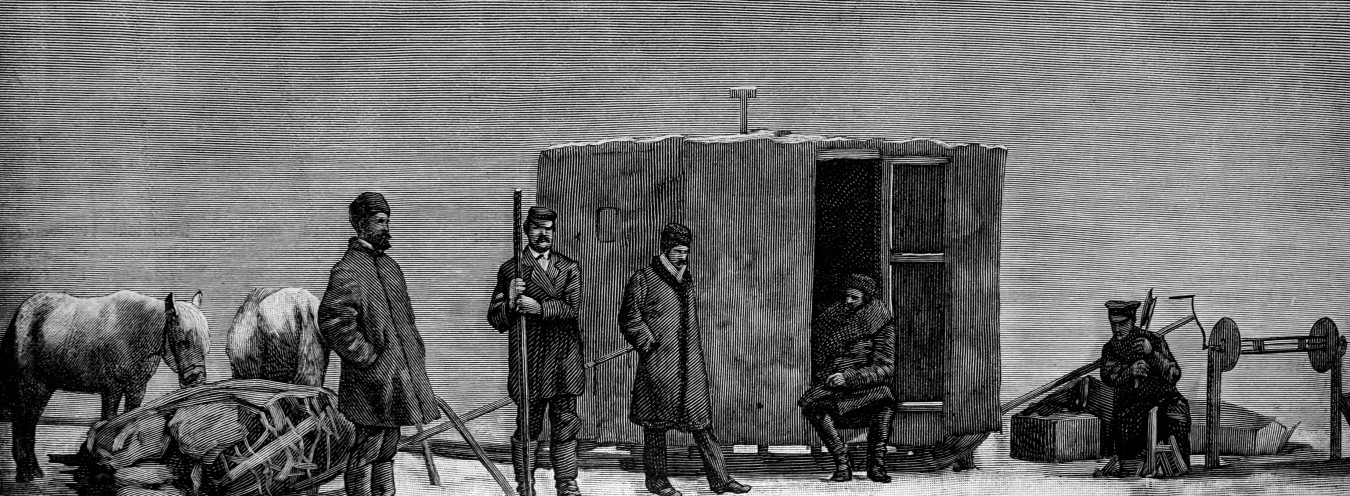

Wokulski spent seven years in Siberia, mainly in Irkutsk. He returned to Warsaw in the autumn of 1870 thanks to the amnesty of the late 1860s. He came back dressed in a sealskin over-coat, with a beard like a brigand and 600 roubles, which he most likely earned by giving private lessons to the children of upper-class Russians, an activity practiced by many exiles. In his conversation with Rzecki, Wokulski voices favourable opinions about Siberia and its inhabitants: What was that country like?’ ‘Not bad.’ ‘Hm …And the people?’ ‘Not bad.’ He does not feel enmity towards Russians, which is evidenced by his later social and business relationship with Suzin, whom he met when in exile. His stay in Siberia was a turning point in his biography: Wokulski discarded the ideals of political romanticism (the faith in the meaning of conspiracy and insurrections) and dedicated himself to science (you probably don’t know I’m a scholar now. I’ve even acquired several diplomas from scientific societies in St Petersburg). When constructing this plotline, Prus referred to the well-known fact that many exiles engaged in scientific research in Siberia, and they were supported by the Eastern Siberia chapter of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, whose headquarters were located in Irkutsk. In some cases, scholarly activity helped them get an early release from the sentence. It remains unclear, however, whether this explains Wokulski’s biography. We can assume that the protagonist conducted also research in the Ural Mountains: He remembered how, during his travels in the Urals, a certain scholar who had discovered a new mineral sought his advice: how to name it? In Siberia, Wokulski got to know the most renowned scholars among the post-January-Rising exiles: geologist and geographer Jan Czerski, Benedykt Dybowski (who researched the flora and fauna of Lake Baikal), and natural scientist Aleksander Czekanowski. Interestingly, they gained the fame of scholars and explorers of Siberia only after 1870. Józef Bachórz accurately summarises the significance of the exile episode in Wokulski’s biography: What happened to Wokulski in Siberia and continues after his return to Poland can be depicted with a paraphrase of the famous statement by Kamil Cyprian Norwid: his Polishness was complemented with humanity. He did not get rid of it […], but he broke free from the schemata and stereotypes that it imposed. In the way that the exile is depicted in the novel, Prus breaks with the martyrological myth of Siberia imposed by Romantic culture on collective imagination. He does not expose any moments of torment, although it is assumed that Wokulski’s red hands result from frostbite in Siberia.

The memories of Siberia return to Wokulski many times in the course of the novel’s plot, most frequently in situations that are especially moving for the protagonist. The most powerful moment when the memories return is when he sees Izabela Łęcka in the theatre for the first time. The colour and of her eyes bring him associations with the region and with Romantic literature, as a crypto-quote from “Anhelli,” a poem by Juliusz Słowacki, which constructs a martyrological and bitter myth of the land of exile comes to his mind: He gazed still more intently into her dreaming eyes and recalled, without knowing why, the limitless tranquillity of the Siberian steppe, where sometimes it was so hushed that you could almost hear the rustle of souls flying back to the West. Thus begins the love affair of Wokulski’s life.

→ Censorship; → Aesopian language; → Russia; → Russians in Warsaw; → Suzin;

Bibliografia

- H. Skok, Polacy nad Bajkałem (1863-1883), Warsaw 1974.

- J. Bachórz, Introduction to B. Prus, Lalka, BN I 262, Wrocław 1991, 1998.

- Z. Trojanowiczowa, Sybir romantyków, Poznań 1993.