Powiśle

[Wokulski] walked along and silently laughed to himself to see labourers interminably waiting for work, craftsmen employed only at patching old clothes, women whose entire property was a basket of stale cakes – and to see ragged men, starving children and unusually dirty women. (69)

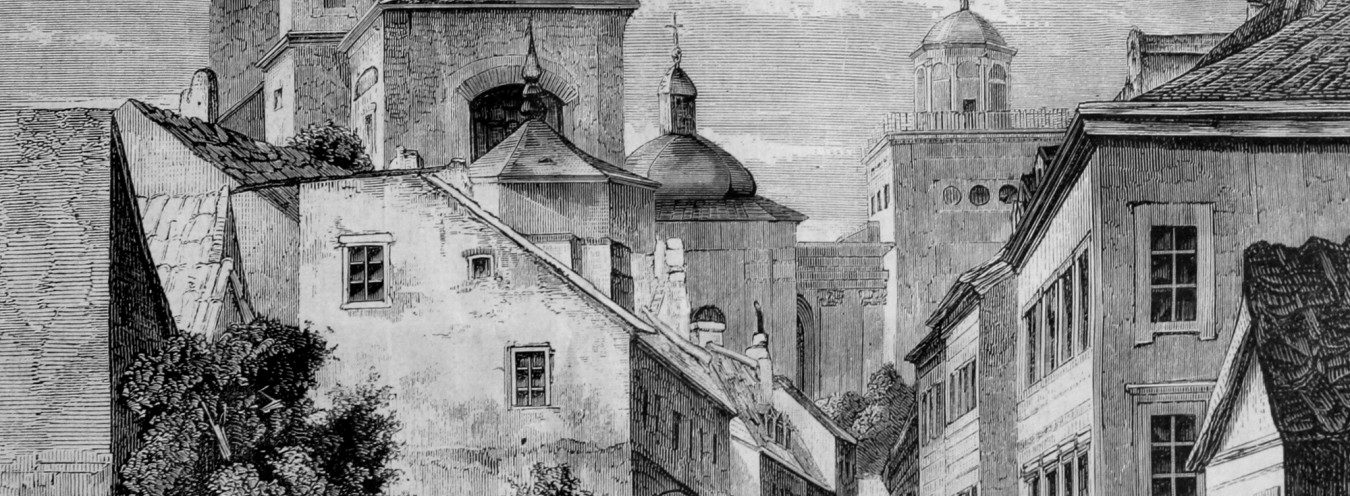

Inhabited by the poorest Varsovians, Powiśle stretched along the Vistula river to the New Town: from Solec Street in the south to Nowy Zdjazd Street and Kierbedź Bridge (opened in 1864) in the north. This neighbourhood of ramshackle houses, neglected and devoid of fundamental urban facilities, in the days of The Doll was beginning to become modernised. The growth of the industry led to the use of its plots for the construction of factories and government buildings; along the river, a narrow stone-paved boulevard was made, and the city authorities planned an intensive development of the district. The first grand project (which impressed Europe) was supposed to be the construction of wide, elegant boulevards, which would open the rich city centre to the embankment and give a commanding view of the river. The large scope of these plans was a topic discussed in serious conversations in The Doll: Upon my word, there’s a great deal of excitement in Paris about those boulevards. Have you replied? Wokulski was also fascinated with the vision of the boulevards – it was connected in his mind with the idea of the betterment of the poor people’s lives. If the banks were to be reinforced avenues, it would become the most beautiful part of the city: buildings, shops, boulevards.

Wokulski’s walk from the centre to the Vistula is depicted twice in the novel. Each time, he stops on his way to direct his watchful gaze at the city skyline. Once, it is beautiful and joyful; the other time, it is desperately downcast. Its image is as changeable as the character’s emotions. When Wokulski cherishes hopes for Izabela’s favour, his happiness adds colour to his world view. [H]e reached Aleje Jerozolimskie and turned towards the Vistula. The brisk east wind enveloped him […]. He smiled to see a sand-carter and his load weighing down a wretched nag and its long cart, while a spectre begging seemed to him a very pleasant old lady. He enjoyed the whistle of a factory, and would have liked to talk to a crowd of delightful little boys. He does not notice that the delightful little boys are throwing stones at passing Jews.

When the protagonist is despondent, he perceives the same district in a different way: it is an embodiment of evil, poverty, and vice, a terrible threat to the rest of the city: Here, occupying several acres of space, was a hill of the most hideous garbage, stinking, almost moving under the sun, while only a few dozen yards away lay the reservoirs from which Warsaw drank. It turns into a symbol of the loss of hope, of decline, illness and garbage.