Socio-cultural and Political Events, 1878-1879

Immediately after dinner [Małgorzata Mincel] went to meetings of ladies who deserted their husbands and children to busy themselves with gossip in the expectation of great events. In the evenings, gentlemen would call on her: but they used to pack her off into the kitchen without even speaking to her. (319)

The action of the novel develops over the course of almost two years, between March 1878 and October 1879. That period saw many real-life political, social, and cultural events, both in the Polish territories and abroad. A lot of them are mentioned by Prus in his weekly press columns Kroniki as well as in The Doll. Incidents selected for inclusion in his writing had a direct impact on the author and his contemporaries by shaping the nation’s history and everyday life in the nineteenth century.

In 1878, Prus had an episode of acute chronic nervous strain after he was slapped in the face by socialist students, offended by some unfavourable comments he made about their behaviour in a public lecture by Włodzimierz Spasowicz. He withdrew from work for two months, and then limited his activity to writing columns exclusively for the Kurier Warszawski. The growing fear of further attacks resulted in increased vigilance. Prus was more than ever trying to control his emotions, stay concentrated and double-check all the information he wanted to include in his writing. As noted by Józef Bachórz, this could be the reason why the novel contains so many specific details that turn out to be true on closer inspection, even in second-rate matters such as the weather (e.g., it appears that the Holy Week Wednesday of 18 April 1878 really was exceptionally warm and sunny for that time of year). Prus also managed to deal with the initial shock by direct, decisive action: he eventually sent his seconds to challenge the main assailant, Sawicki, to a duel (the student declined, excusing himself with illness). The old tradition of “giving satisfaction” in a duel was still common in the nineteenth century, as represented through the novel’s characters inclined to settle arguments in this ritual one-on-one combat: Stanisław Wokulski, Ignacy Rzecki, and Baron Krzeszowski. In another analogy, Wokulski frequents the theatre, concerts or lectures in Warsaw before and after his business stay in Bulgaria in the hope of catching sight of Izabela Łęcka, just like Prus the columnist did in search of the topics to be discussed in his weekly columns Kroniki.

The characters of the novel appear to respond quite fast to current affairs. For example, when Victor Emmanuel II of Italy dies on 9 January 1878, Tomasz Łęcki wears black crepe on his hat as a sign of mourning for the king who allegedly used to be charmed by the beauty of Łęcki’s daughter. Izabela Łęcka, in turn, wishes to go to the Paris Exhibition, which actually opened on 1 May 1878, even at the cost of having Wokulski as a companion.

In his weekly press columns Kroniki, Prus also mentions a lottery event with a masquerade and fireworks, organised by the Games Committee of the Warsaw Charity Society in the Swiss Valley park during the annual St John’s Festival. It was much talked about because of a row over the prize with the then-famous Warsaw ballet dancer, Władysław Przedpełski, voicing the loudest complaints.

The fictional world of The Doll is built around actual cultural events, such as theatrical performances, concerts and public talks (usually held at the Commercial Club, which was a place of social meetings and public activity). In the first half of 1878, the Grand Theatre in Warsaw staged Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera titled Les Huguenots, watched by Wokulski’s shop assistant Mraczewski with a certain Matilda, as noted down by Rzecki in his private journal.

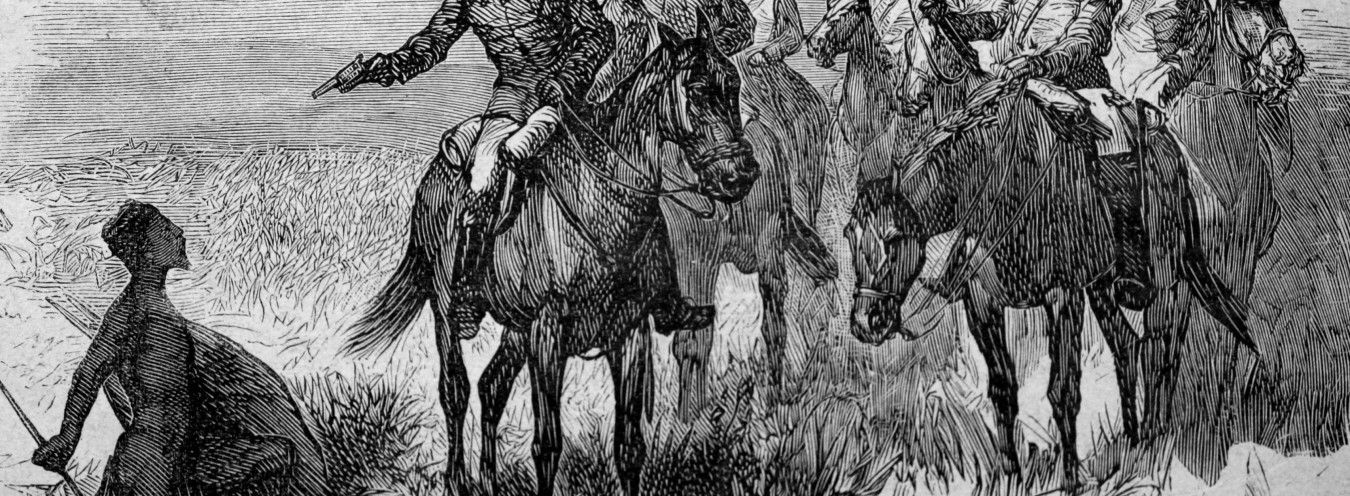

In addition, The Doll contains references to the then current events concerning literature, discoveries and pioneer expeditions, such as a journey into the African continent (described in Henry Stanley’s Through the Dark Continent of 1878, translated into Polish one year later). This is how explorers like these present themselves in the eyes of Izabela: Amidst the permanent population of this enchanted world an ordinary mortal would sometimes appear. […] He might be an engineer. […] He might be a traveller who was said to have discovered a new part of the globe, had been shipwrecked on a desert island and even tasted human flesh. In the privacy of her own room, Izabela Łęcka reads the most recent novel by Émile Zola, Une page d’amour, published in April 1878.

Still, there is nothing that absorbs the novel’s Varsovians more than politics. Friends and acquaintances come together in a celebrated restaurant and, surrounded by clouds of cigar smoke, and sitting over dark bottles, they comment on and try to predict the consequences of current events and facts: the Russo-Turkish war (a European war […] is just around the corner), the Treaty of San Stefano, the Congress of Berlin. They discuss the arming of England, […] some called Bismarck a genius, […] some criticised the behaviour of President MacMahon.

Apart from the Chancellor of Germany Otto von Bismarck, who played a political game against Russians, The Doll also mentions other cultural, social, and political personages of Europe at that time, including Klemens von Metternich, Lord Palmerston (British Prime Minister and supporter of the Polish and Belgian revolutionary movements), Pope Leon XIII, Napoleon III and his son Napoleon IV, Benjamin Disraeli (British Prime Minister, politician and writer held in high esteem by Queen Victoria), and Ernesto Rossi (an Italian actor who appeared in Warsaw and was well known for his Shakespearean roles).

→ Dolina Szwajcarska (Swiss Valley Park); → The Past; → Theatre;

Bibliografia

- J. Bachórz, Introduction to B. Prus, Lalka, BN I 262, Wrocław 1991, 1998.

- Bolesław Prus 1847-1912. Kalendarz życia i twórczości, ed. and annotated by K. Tokarzówna and S. Fita, ed. Z. Szweykowski, Warsaw 1969.

- B. Prus, Kroniki, ed. and annotated by Z. Szweykowski, vol. 3, Warsaw 1954.