Theatre

In the evenings, […] they drove to […] the theatre, there to see another artificial world, in which heroes rarely ate or worked, but frequently talked to themselves, where the infidelity of a woman caused tremendous catastrophes and where a lover, slain by the husband in Act Five, would rise from the dead next day to perpetrate the same mistakes and talk to himself without being heard by the person standing next to him. (36)

In the 1870s, the position of the director of the Warsaw Theatre Directorate was held by Sergei Muchanov, a Russian. He managed to pull the Polish theatre out of the apathy it had sunk into after the January Rising. Playhouses came alive. Accomplished actors were engaged, including the brilliant Helena Modrzejewska (who, however, left Poland in 1976 and appeared on the Warsaw stage only on her visits to the city).

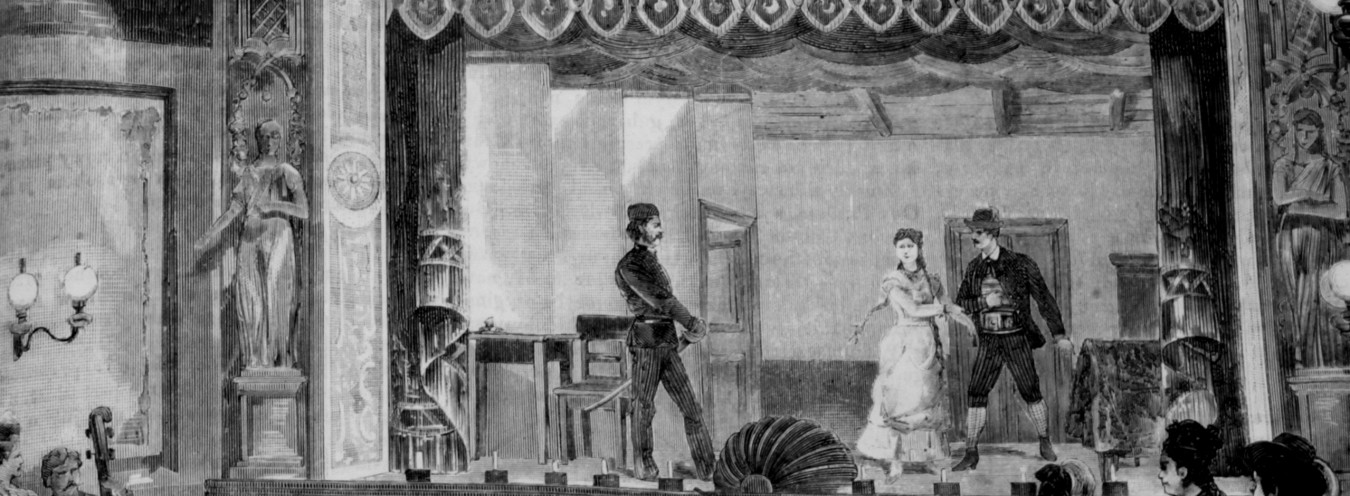

At that time, Warsaw boasted seven theatres, four of which operated regularly throughout the year. The most prominent one was the Teatr Wielki (Grand Theatre). Its repertoire significantly expanded thanks to Helena Modrzejewska, as directors looked for parts and dramatic works she would like to work on, and the authority of Muchanov kept censors in check. Warsaw saw stage adaptations of plays by Shakespeare and Schiller as well as two premieres of Słowacki’s Romantic drama. Teatr Rozmaitości, situated in the vicinity of the Teatr Wielki, also enjoyed a considerable popularity. There were two more all-year theatres nearby: Teatr Mały (Small Theatre) in Daniłowiczowska Street and Teatr Nowy (New Theatre) in Królewska Street. Seasonal theatres included the fashionable summer theatre in the Saski Park, the well-liked Amphitheatre on the Isle in Łazienki park, and the court theatre in Łazienki’s Old Orangery that held performances only when the Tsar and his entourage came to Warsaw.

The choice of lighter repertory was becoming wider and wider. Apart from the evergreen plays by Aleksander Fredro, theatres staged comedies by the then contemporary Polish playwrights. Repertoires underwent constant changes: if a play was on ten times, it was considered a success. The price that one was ready to pay for the ticket was an indicator of one’s social status. The most expensive seats in the boxes in the ground floor and balcony were eight roubles each; a seat in the ground-floor stalls cost over one rouble. The cheapest tickets allowed the holder to enter the gallery (the highest part of the auditorium), usually crowded with craftsmen, apprentices, students and priests – in plain clothes, of course. Acclaimed actors were given a cult treatment. They received flowers on stage, got standing ovations, and returned many times for the curtain call. Advertising started to be used more effectively, with photographs of celebrities put in shop window displays on the days of premieres, benefit concerts and guest performances. They were even put on candy wrappers, and one restaurant even served sirloin à la Żółkowski (after Alojzy Żółkowski, a celebrated actor). The success of each play largely depended on the claque and other voices from the gallery audience, who expressed their opinions in a totally uninhibited manner. Still, the true opinion-forming authorities were editors of daily newspapers.

Warsaw theatres plunged back into crisis with the death of their famous actors Jan Królikowski and Alojzy Żółkowski and the retirement of Muchanov from the Warsaw Theatre Directorate.

In The Doll, the theatre is not a dominant motif, but plays a pivotal part: it is there that Stanisław Wokulski sees Izabela Łęcka for the first time, instantly falling in love with her. This incident determines his fate: perhaps the haberdashery merchant might have become a good natural scientist, had he not been once to the theatre and seen Izabela there. Ever since that first moment, he often attends theatrical performances – not to watch them, however, but to observe Izabela and pander to all her wishes (for example, he makes sure that her idol Rossi is given an impressive ovation).

In the novel, the word “theatre” is also used with a metaphorical meaning in mind. When Prus criticises the nobility, he implies that their lifestyle has adopted theatrical forms and gestures. One of his main characters, Ignacy Rzecki, notes that the rigged court-room auction of Tomasz Łęcki’s house is better than the theatre: for the performers in this official spectacle act more realistically, if not better, than stage players. In addition, as once stated by Jadwiga Misiewicz (Helena Stawska’s mother), looking through the window onto the street is theatre enough for poorer people who are not that much into high culture; and even Baroness Krzeszowska cannot resist observing the apartments of her neighbours through a pair of opera glasses.

Returning to Ignacy Rzecki, his favourite activities include drawing up plans for window displays and then putting the displayed mechanical toys in motion. All too often, however, they evoke a poignant reflection: as he watched the movements of the inanimate objects, he repeated for the thousandth time: ‘Puppets!… All puppets! They think they are doing as they choose, but they only do what the springs command, blind as they are!’ It is believed that Prus drew on Plato’s philosophy for this metaphor of man as an actor and life as theatre.

→ Claque; → The Royal Łazienki Park; → Money;

Bibliografia

- T. Sivert, Teatry warszawskie w latach 1865-1890, in: Teatr polski od 1863 r. do schyłku XIX wieku, ed. T. Sivert, Warsaw 1982.

- Z. Raszewski, Krótka historia teatru polskiego, Warsaw 1997.

- A. Tuszyńska, Gwiazdy i gwizdy: z dziejów publiczności teatralnej 1765-1939, Lublin 2002.