Travels of the Characters in “The Doll”

He went to Odessa, and from there he plans to go to India, from India to China and Japan, then across the Pacific to America. (660)

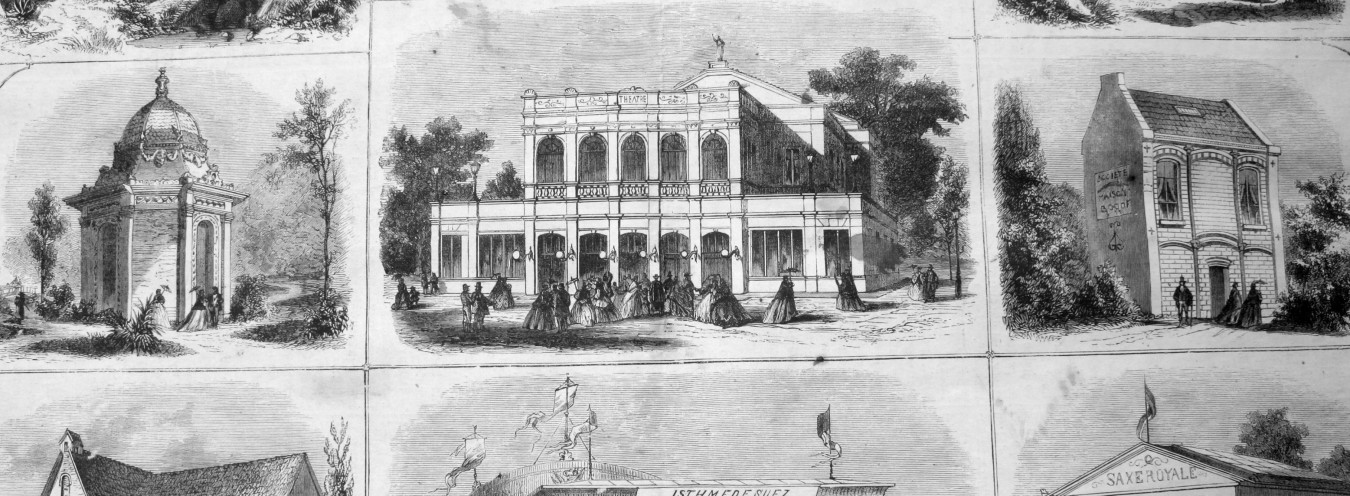

In the nineteenth century, the railway rapidly developed, and the dense network of train connections radically shortened the time of travel as well as made it more comfortable and affordable. At the same time, due to the dramatic financial standing of the residents of the Kingdom of Poland, only the elite could afford to travel across Europe, frequently joining work and leisure. It gave them the opportunity to conduct business deals or connections and lead rich social lives at the same time. In The Doll, this is exemplified by Tomasz Łęcki, who mingles in foreign salons until he gets into debt. Paris was the most popular of the foreign destinations. It is referred to as the centre of the world by Izabela Łęcka and as a favourite city by Kazimiera Wąsowska. Some, as Prus writes in his Kartki z podróży (Travel Notes), travelled to all corners of Europe, where people played roulette and – as Kazimierz Starski, for example – lost fortunes in Monaco or Monte Carlo. Another popular destination were foreign health resorts, or fashionable baths. Ignacy Rzecki dreams about going abroad for a cure to get rid of the silly shortness of breath. Suzin, worried about Wokulski’s health, advises him to call the doctors, go to Karlsbad.

Wokulski travels on business to Bulgaria, where he made his huge fortune, as well as to Moscow and Paris. Julian Ochocki goes as far as St Petersburg to protect the terms of Duchess Zasławska’s will against ungrateful family members. The novel also mentions forced travels. Rzecki participates in the Springtime of Nations in Hungary, and then wanders across different countries for several years. Wokulski is sent to Irkutsk in Siberia for his participation in the January Rising (1863–64). Thanks to meeting renowned Polish researchers Jan Czerski, Aleksander Czekanowski, and Benedykt Dybowski, this exile becomes a unique educational journey, and the character return[s] to Poland almost a scholar.

The nineteenth century is also the time of exotic and distant expeditions to Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas. The character that is presented as world-wise is Starski, who allegedly has been all around the world. He talks about his journeys to impress his female listeners, spinning some incredible yarn. Julian Ochocki – in contrast to the gullible ladies – does not quite believe Starski’s stories. He jokes that he travelled a little (mainly, though, in the bars of Paris and London, as I really can’t believe in that China of his). The rumours about Wokulski’s travels are also barely credible: can we believe that having left Warsaw without a word of explanation after his painful disappointment in love, he went to Asia and America?

At the time, people also travelled across Poland. In The Doll, several places around Warsaw, such as Kraków, Częstochowa, and Skierniewice, are mentioned. This nevertheless happens only in the context of tourism, business travel, or family reunions as the beautiful phenomenon of exploring one’s own country instead of travelling abroad disappeared. The custom of the famous walking trips, so popular with the previous generation (especially among writers and artists), died out.

→ Baedeker; → Passports; → Prus’s Travels; → Poles in Siberia; → Holiday;

Bibliografia

- S. Burkot, Polskie podróżopisarstwo romantyczne, Warsaw 1988.

- J. Kamionka-Straszakowa, „Do ziemi naszej.” Podróże romantyków, Kraków 1988.

- Podróż i literatura 1864-1914, ed. E. Ihnatowicz, Warsaw 2008.