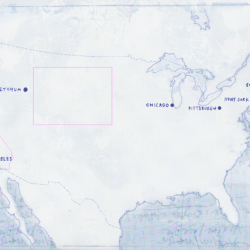

The United States at the time of Sienkiewicz’s journey

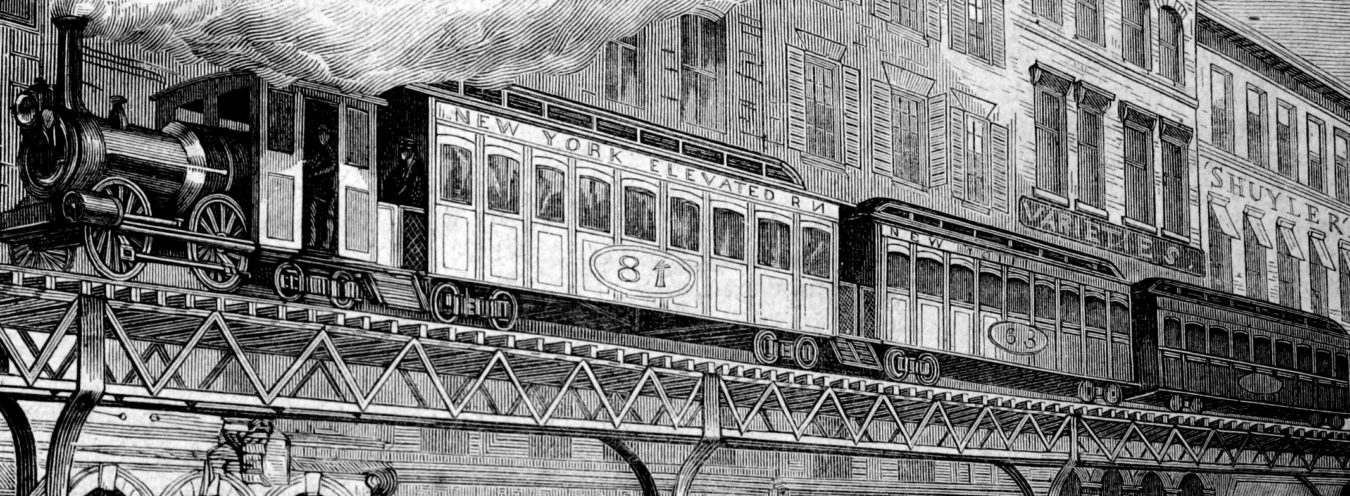

Sienkiewicz arrives in the States around March 1, 1876.[1] Having spent a week or so in New York (the episode which so suggestively yielded a critical depiction in Portrait of America that those who analyze the text, overwhelmed by the dichotomy between the tumult of the New York streets, noisy, gaudy, and sparkling with gold, and the sunny realm of California with its endless vistas and apparently limitless possibilities, sometimes forget the fundamental disparity between what was but a mere brush with New York and a long stay in the American frontier for Sienkiewicz[2]), he leaves for California. Two stopovers later – a planned one in Chicago and one forced by a blizzard in Wyoming, where he sees a Native American for the very first time at the Ketchum railway station[3] – around March 16 Sienkiewicz reaches San Francisco. In June, he moves to Anaheim, which at the time is little more than a village (and not yet a part of Los Angeles), and takes part in preparing the future establishment of a “colony” of Karol Chłapowski, Helena Modrzejewska, and their close friends, which is why he actually decided to embark on the journey in the first place. He is, however, arguably less engaged in the creation a future phalanstère than happy to be able to enjoy local trips, hunting, and life much closer to nature than the one which he led in Warsaw since he had come of age. He is also clearly fascinated by the life of a colonist in the still half-wild borderlands of a great country. The Chłapowski family arrives on November 30, but his relationship with them soon begins to deteriorate, partially perhaps due to Sienkiewicz’s fascination with Modrzejewska (which her husband did not appreciate at all), but certainly also because of the catastrophically bad state of the farm they were trying to settle in.[4] One might well wonder whether Sienkiewicz’s apparently scant participation in the efforts to establish the “colony” was not another significant factor. According to his correspondence and Portrait of America, Sienkiewicz leaves Anaheim very often. He visits the mountains for the third time, travels in the Mojave Desert, and visits Los Angeles and San Francisco. One may well have the impression that Sienkiewicz was considerably more interested in living among the locals than with his compatriots. Towards the end of March, he leaves Anaheim for good and embarks on a journey that will take months: he spends several weeks in each of the places he passes through – in Sebastopol, in Haywood (in the vicinity of San Francisco), in the Mariposa country (on the verge of what today is the Yosemite National Park), and finally in San Francisco, where he arrives in July. In October, he probably takes part in a month-long hunting trip to the Wyoming territory (in the South-West of what today is the state of Wyoming). Between January and February, he embarks on a long journey home. Having stayed in New York considerably longer this time (we know now that the stay features trips to Boston and Pittsburgh), on March 23 or 24 Sienkiewicz boards a Liverpool-bound ship and leaves the New World for good.

As he is traveling in the States, there occur events that are both attentively followed by Americans and historically momentous when it comes to the changes happening in the country and the nation. October 1876 sees the presidential elections that close the two-term rule of Ulysses S. Grant, a breakthrough period for the States. Grant’s presidency ushers in what historians have called the Gilded Age, which fosters the development of industry, the re-creation of the foundations of the state after the tragedy of the Civil War, and the merging of California with the rest of the country – that is to say, the colonization of the so-called Wild West, which since 1848 had been formally a part of the country but which lacked all state organization and effectively remained a domain of Native Americans.[5] But the Gilded Age also brings about previously unimaginable levels of corruption, puts a final end to the Protestant work ethic in trade and industry, and – a phenomenon increasingly visible once Grant leaves the office – moves the actual center of power away from the world of politicians and into the world of plutocrats. The 1876 elections will come to be remembered as one of the gravest constitutional crises in the history of the States. Their final outcome is referred to as the Compromise of 1877. Reached in March by the representatives of the two parties (after fraud accusations effectively subverted several attempts to identify the winners of the electoral votes in three disputed states), it proclaimed Rutherford B. Hayes of the Republican Party to be the president of the United States – although it is his Democratic opponent, Samuel Tilden, who actually received more electoral votes.[6] The Compromise of 1877 guarantees the final withdrawal of the army from the Southern states, which is meant to ensure a solidification of the post-war order – at the price of significant concessions to the South with respect to racial issues. But that which Americans are more engrossed in at the time is what is taking place in the West of the country.

Przypisy

- All the established dates of the American journey quoted after Julian Krzyżanowski, Kalendarz życia i twórczości Henryka Sienkiewicza [The calendar of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s life and works], edited and with notes by Maria Bokszczanin, Warsaw 2012.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z podróży do Ameryki, [Portrait of America: Letters of Henryk Sienkiewicz], edited by Julian Krzyżanowski, Warsaw 2004, pp. 78–107.

- A letter to Stefania Leo from December 3, 1876, see Henryk Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 3, edited by Maria Bokszczanin, Warsaw 2007, pp. 437–438. See also H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z podróży [Portrait of America: Letters of Henryk Sienkiewicz], pp. 137–143.

- Compare Helena Modrzejewska, Karol Chłapowski, Listy [Letters], vols. 1–2, edited by Alicja Kędziora and Emil Orzechowski, Warsaw 2015.

- Compare S. D. Cashman, America in the Gilded Age, New York 1984; Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, New York 1988.

- Compare M. A. Jones, The Limits of Liberty: American History, Oxford 1983, pp. 258–259; S. D. Cashman, op. cit., pp. 200–202.