The American frontier

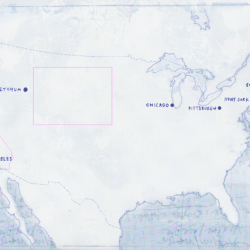

Sienkiewicz was undoubtedly fascinated with the American frontier. Portrait of America clearly records the birth of that fascination and its development. If one were to describe it, several contributing factors could be differentiated. The first aspect is the escapist myth. It accompanies Sienkiewicz’s American voyage almost from the very start: after all, the attempt of the Chłapowskis to establish a commune at the ends of the world, living in accordance with nature and putting the rules of the utopian economy into practice was escapist in its character. From the very beginning, after a very short stay in New York, there is a very clear dichotomy in Portrait of America of the rich American metropolises developing instantaneously and impossible to bear, and the interior, a land of infinite space and possibilities, where a human being could live in accordance with oneself or be able to find oneself. The second element of Sienkiewicz’s fascination with the frontier is the initiation myth. California is a space of self-discovery and maturation. A city-dweller becomes a hunter and wanderer who feels at home in the mountains, in the wilderness and in the desert. The narrative poetics is unambiguously that of initiation – a boy becomes a man (this is obviously a stylistic device, Sienkiewicz is then 30 years old. On the other hand, if we are discussing a man entering the age in which Christ died, in Slavic cultures called “Christ’s age,” the physical and spiritual heyday, this sort of narration could be appropriate). It seems, however, not least on the grounds of the writer’s letters from that period, that it is not just a stylistic device. It is also seeing oneself exactly the person one wishes to be: entering into the mindset of a man of wide open spaces. The third factor seems to be of a very personal nature – everything points to the fact that Sienkiewicz was happy in California.

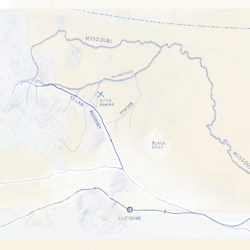

However, apart from the personal transformation during the escape to another world, it is also important in which world, which space, the transformation takes place. In California, it takes place in a physical dimension, its environment is a challenge in itself – a challenge especially difficult for a city man, a man of forest-covered lowlands, who now climbs high mountains, crosses the desert, hikes along the seashore, and when he is finally in the woods, he can see trees of previously unimaginable size. These spaces are occupied by other conquerors – hunters, trappers, and also farmers, but they are in a completely different situation to the one he knows from his home. Unlike the oppressed peasants from Poland, in California, they are colonizers (sometimes in the first, sometimes the second or third generation) attempting to subdue the unruly land. There are narrations in this space as well, most of all heroic, celebrating the hunters’ victories or military defeats of Native Americans and the American conquest of California. In the New York part of Portrait of America, it is already abundantly clear how much the writer is interested in the frontier war narrative (Sitting Bull and Custer). The echoes of war on the Wyoming territory would accompany him throughout his entire journey. It is as if he found himself in a world of fairy tales and legends. The familiar European dimension of legends takes, however, a different shape here – instead of knights – there is cavalry, instead of adventurers colonizing the eastern borderland of Poland – there are trappers, instead of Cossacks or Tatars – Native Americans.

It seems a peculiar paradox that the slowly rising conservatism of Sienkiewicz rejects the American greedy city, sprawling without containment or consideration, and embraces the lands that change even more quickly and are transformed even more ruthlessly. Upon a closer look, it ceases to be paradoxical. Sienkiewicz’s unique perspective can transform the Western frontier of the United States into a space not so much victimized by ravenous progress as one that returns to the source. A space in which a republic is colonizing its own borderland (this time in the West), fighting the wilderness and the wild natives is an everyday event, and the knight culture is not so much a memory as a tribal necessity. Manifest Destiny, the idea of a singular predestination of the United States’ citizens towards the rule over American lands, that is, primarily, conquering California, was invented in the 1840s as an ideological justification for the Mexican War (a war perceived by a part of the nation as unfair, invasive and shameful).[1] It gave rise to controversy amongst Americans from its very conception, yet by in the 1870s, though still a questionable belief; it was already firmly rooted in American culture. Sienkiewicz, then, apart from familiar narrations dressed in new robes, here finds the messianism of a rising empire. The Republic that he observes from the beginning of his stay in the US is attached to freedom and democracy, which are not, however, available for all. It is dissentious, sprawling, enormously rich, desiring new lands, corrupt, heroic, on horseback, still bleeding after the Civil War. There is much here of another state, another republic, also a literary one, which he puts to paper almost a decade later.