California

Sienkiewicz arrives in California almost thirty years after it was incorporated into the United States at a time when American colonization is still an ongoing and open process. The writer encounters there a difficult but permanent coexistence of two nations which, for differing reasons, feel they are the masters of this land (maybe even three if you take the remnants of the Native Indian population described in Portrait of America into account[1]). He also keeps coming into contact with the ongoing process of the colonization of a virgin land – the harbor city of San Francisco may have developed very quickly, yet in its close proximity, there are still farmers trying to transform the wasteland into arable lands and wandering hunters, who are a living memory of the exploration that took place thirty years prior.[2] The California of farmers and hunters attracts Sienkiewicz’s attention to the highest degree.

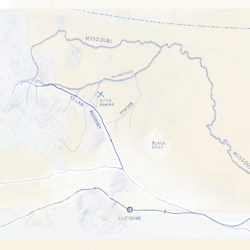

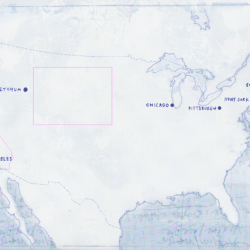

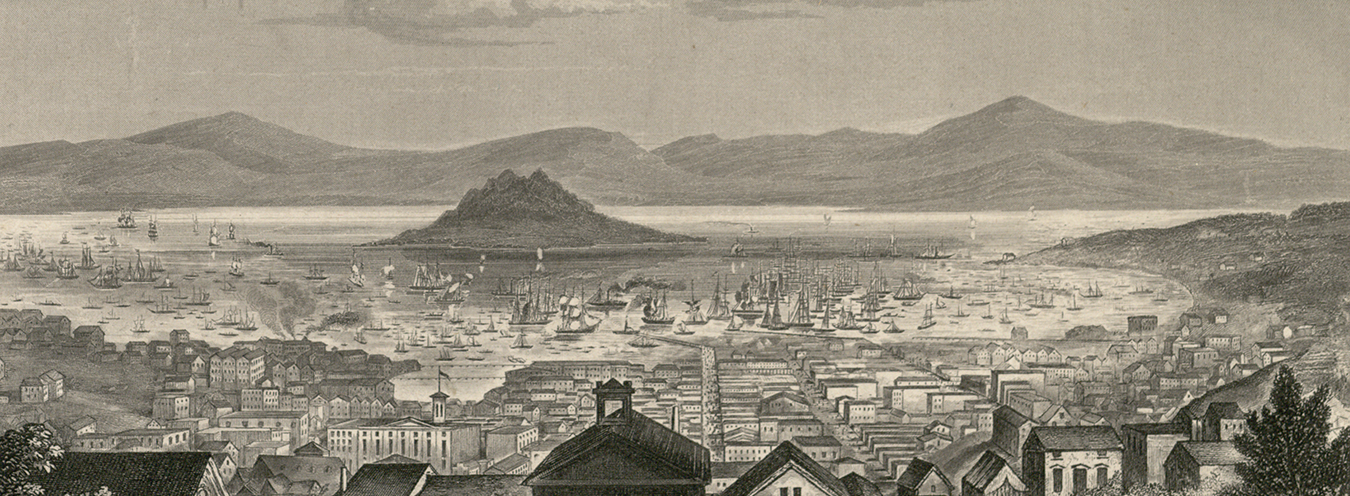

California, where Sienkiewicz had lived for almost two years, was a peculiar place, a “state within a state” in a way. Two issues contributed to that: its separation from all the other states and its unique social and cultural structure. In 1850, barely two years after the acquisition of California by the United States pursuant to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it gained the status of a state (the state borders charted then are still in effect). Between 1850 and the outbreak of the Civil War among the territories incorporated into the United States and lying to the West of the “Old Union,” the only ones to gain state status were: the remote Minnesota (1858) and Oregon, neighboring California (1859), and just after it Kansas (1861), where the dispute over its legal status had been one of the pretexts leading to the outbreak of the Civil War. Before Sienkiewicz came to America, three more states were established in the West: Nevada (1864), Iowa (1867), and, almost simultaneously to the writer’s arrival, Colorado (1876); subsequent states were established only towards the end of the 1880s.[3] What follows is the unique position of California among the other parts of the US as a state demarcating the Western frontier for almost a quarter of a century, yet separated from the other states by miles of half-wilderness crossed only by lone roads, very slowly substituted with the Trans-American railway. On the one hand, these were the borderlands of an empire; on the other, however, because of its remoteness and the well-developed community of Iberophone Californians, more numerous than Americans, California presented a lot of features of a colony. Apart from imposing the new authorities on the local people by the newly arrived ones, other issues that made it resemble a colony would be the exploration of unused vast areas of land, forming new settlements, and fertilizing the Californian soil to transform it into agricultural acreage. One could view the various actions American society undertook towards its new state from this angle, starting with the utilization of the gold fever, which broke out just after the incorporation of California by the United States, to the change in the demographical structure of the new territory, to the priority treatment of the flow of settlers to the farthest parts of the West (safety of the trails, building the railway). If one were, nevertheless, to regard California as an almost colonial territory, it is striking how differently the settled, non-American populace is treated. We are touching here, of course, upon the subject of very difficult relations, imposing the dominance (linguistic, political) of a less numerous but much stronger nation, but this is not an act of conquering, an attempt at extermination or complete domination through a ruthless cultural war.[4] It is also worth mentioning that American colonization at the time of the acquisition of California by the United States was a phenomenon which had already lasted more than one generation, even if it was limited (those were mostly rural settlements in the Sacramento Valley, and this is why to this day Sacramento, as a historical outpost of American people in California, remains the capital of the state).[5]Hence we can rather speak of two concurrent strategies: coexistence with the Ibero-American population (concentrated mainly in the South of the state, around San Diego and Los Angeles; Sienkiewicz primarily came into contact with it when he lived in Anaheim) and the development of colonization, especially in places with adequate natural conditions and sparsely populated before the annexation (the flourishing of San Francisco, in 1848 a small settlement by the sea and a rapidly developing harbor town in the 1870s).

Przypisy

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z podróży [Portrait of America], pp. 343–361.

- Compare Stephen Schwartz, From West to East. California and the Making of the American Mind, New York 1998, pp. 73–138; Ray A. Billington, The Far West Frontier 1830–1860, New York 1956.

- M. Jones, op. cit.

- Compare S. Schwartz, op. cit.

- H. Sides, op. cit., pp. 114–116.