Charity

In addition to its many shortcomings, Warsaw has always been a city brimming with mercy. Every year, dozens of thousands of roubles are spent on ‘charitable causes,’ complained Prus in his weekly press columns Kroniki. He went even further in the Kurier Codzienny newspaper by advocating fervently against giving alms. In The Doll, Wokulski voices a view similar to the author’s when he says that charity breeds insolent loafers. Unfortunately, many benefactors were all too happy to stop caring at the point of giving money, thus gaining a reputation of a generous patron at little expense and even less effort. For example, Izabela took an active part in all these philanthropic activities; she also offered money donations, her eyes tearing up at the thought of how sensitive and kind-hearted she was.

As a publicist, Prus argued that the issues of poverty and mendicancy could be only solved by ensuring that every poor person has a job. That is why he supported the idea of establishing special workshops and let people train there as cobblers, locksmiths, carpenters, tailors; he also suggested an equivalent of employment agencies. Once again, Wokulski is a vehicle for these views: there is a simple remedy: compulsory labour, properly renumerated. That alone can bring forth better individuals and wipe out evil without a fuss… We would have an active population where today we have hungry or sick people. Wokulski’s own good deeds towards the poor are the direct application of the above, as the support he gives to the family of cart driver Wysocki, handyman Węgiełek, and prostitute Maria makes it possible for them to earn their living in a decent way.

Unfortunately, Warsaw did not value effective social activity even half as much as charity tombolas, parties, concerts and exhibitions – events that did not bring the profits required for assisting the poor, but were a great self-promotion opportunity. That fact was deplored by the novel’s author and painfully experienced by Wokulski, contemptuously called a parvenu by other characters.

Charity work that made an integral part of the aristocratic social life in The Doll is like a hypocritical, caricature version of itself. Izabela Łęcka is anxiously waiting for an invitation to accept charitable offerings at church during Holy Week; once it arrives, she breathes a sigh of relief that she is not dismissively left out, which would be a social snub. Wokulski looks at the Easter collection from a different perspective when he arrives. In various parts of the church he saw tables spread with carpets, on them trays full of bank-notes, silver and gold, and near them were ladies seated in comfortable chairs, dressed in furs, feather and velvet, talking and laughing as if this was a social gathering. ‘I won’t join that charitable market-place,’ says Wokulski to himself.

For Polish aristocrats, charity was the matter of ambition, if not of honour. Countess Karolowa takes advantage of Wokulski’s weak spot for Izabela to obtain his generous donations for the orphanage she manages and thus make it the first in the town. Also the Prince felt personally offended when Wokulski, by now known for his open-handedness, for two months had not given a penny to the poor people he patronised.

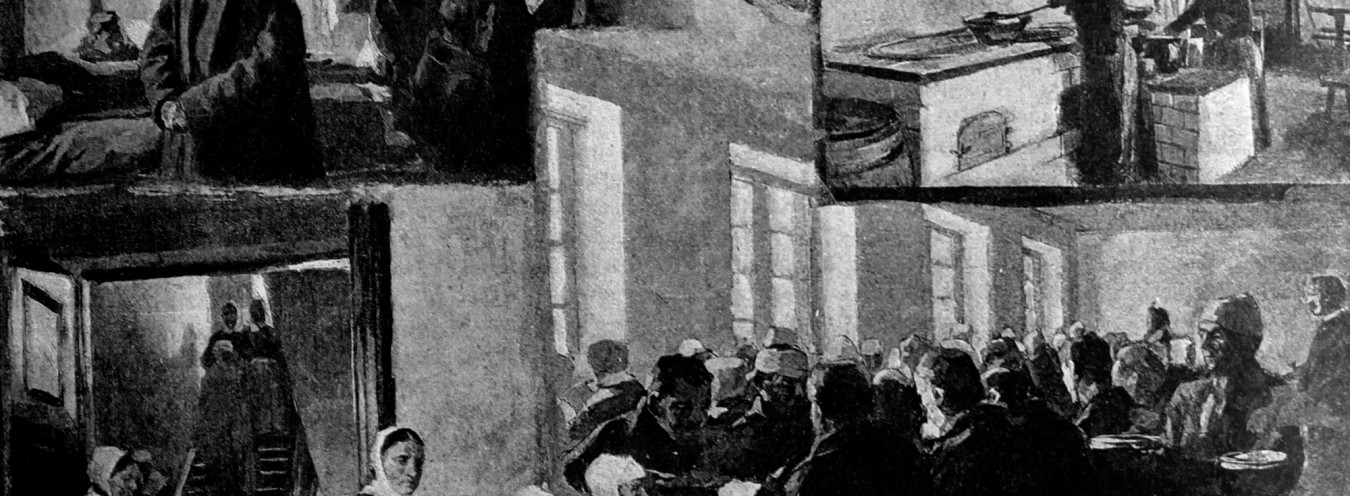

The charitable actions of Warsaw’s high society are depicted by Prus with such contempt that the portrayal must be a bit unjust and distorted. In reality, many wealthy Varsovians of that time were personally engaged in charity work that actually made a difference (e.g., feeding the hungry, providing child care for the poor, running orphanages and asylums, training people for different trades). This much is evidenced by the contemporary statistics indicating a large number of care institutions and their charges. It was considered to be a sort of patriotic mission to give a helping hand to fellow Poles, saving them from the stifling oppression dealt by the Tsarist authorities.

An honourable exception to The Doll’s noble but not noble-minded benefactors can be found in the example of Duchess Zasławska. She is involved in the real work at the grass-roots level at her estate, personally looking to the well-being of peasant families, education of their children, and proper care for the elderly. Towards the end of her life, she bequeathes all her property to charity.

→ Orphanages; → The Charitable Society; → The Poor; → Utopia;

Bibliografia

B. Prus, Kroniki, vol.16, Warsaw 1966.

B. Prus, Kroniki, selected by S. Fita, vol. 1, Warsaw 1987.

E. Mazur, Dobroczynność w Warszawie XIX wieku, Warsaw 1999.

E. Leś, Zarys historii dobroczynności i filantropii w Polsce, Warsaw 2001.