Discoveries and Inventions

The popular name given to the nineteenth century, “The Age of Steam and Electricity,” combines two vital achievements of scientific thought at that time: the invention of a steam engine and the discovery of electricity. Primitive steam machines were designed in Europe as early as in the end of the eighteenth century to power water pumps in mines and collieries, but it was not until the following century that the invention was perfected and widely applied. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, steam propulsion brought about a revolution in transport – first on waterways (1807 marked the launch of the first steam-powered ship) and then on land (the first railway was opened in 1825). The Doll describes a possible breakthrough with yet another application of steam power: Stanisław Wokulski and Julian Ochocki think about using steam engines to power airships. The former character wants to build a perpetual motion machine in his youth, and then ponders the problem of steering balloons, while the latter dreams of constructing a flying machine. During his visit to Paris, Wokulski experiences a great captive balloon ride, almost 2,000 feet up in the air, and sees the city from that amazing point of view. Here, Prus alludes to events which actually took place. The balloon described by Wokulski in conversation in Zasławek was actually prepared for the Paris World’s Fair of 1878 (Exposition Universelle). The creator of the hot air balloon, Henri Giffard, had already managed a successful dirigible flight: in 1852, a vehicle designed by him (shaped like a giant cigar, with a steam-powered propeller) covered a small distance with a speed of around 8km/h. The Fair also featured, among other French achievements, a monoplane, a prototype of a steam-powered plane capable of several-hundred-meter flights.

An interesting characteristic of the discussion of flight in the novel is that air travel is systematically being compared to “sailing.” This is obviously justified when the journey through the air is made in a balloon with no propulsion, or in a relatively slow dirigible, but the sailing reference is made in the novel to all kinds of air travel, also when Ochocki’s designs are discussed. The idea of flying machines in The Doll is developed with definite analogies to the events and achievements of that time, known to Prus, mostly related to wartime manoeuvres on the seas. Since the 1860s and the American Civil War, these activities had been undergoing radical change caused by a new type of warship, which came to be known as the ironclad. Using a powerful steam engine for propulsion allowed for the construction of larger ships, armed with bigger-calibre guns which were being placed in revolving turrets (amidships, and then – also on the bow and stern). These ships could also be protected from enemy fire with a thicker metal armour – their resilience further improved by switching the propulsion from vulnerable side paddle wheels to screw propellers. Ochocki’s project is an aerial equivalent of such a warship, as he does mention a machine weighed down like a battleship. This is an idea Wokulski will take to, and it will remain firmly in his imagination as an image of the future, unimaginably successful weapon (armoured ships which could rise in the air!) In Paris, Wokulski advises Suzin in his trade talks with ship builders. It is possible that the object of Suzin’s arms transactions was an order of battleships.

Dynamite is another invention whose origins are military and whose influence on the protagonist’s fate is vital. The explosive, whose composition and technology was patented in 1867 by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, is mentioned several times in The Doll. First, Izabela Łęcka dreams of an engineer who drills through the Alps, crushing the mountains with dynamite charges. Wokulski, whom thoughts of Izabela’s marriage make desperate, contemplates packing the earth with dynamite and blowing it sky high. When the main character finally leaves Warsaw, and when carpenter Węgiełek later reports that the castle in Zasław has been blown up, these two events are perceived as related, especially since – as the novel mentions – Wokulski is seen in Dąbrowa before the explosion, purchasing loads of dynamite. There is also a new explosive material in the novel, offered to Wokulski by Professor Geist during their first meeting in Paris, which was probably also based on dynamite. Geist’s offer remains tied to Wokulski’s primary reason for visiting Paris, which was not the Fair but consultations during Suzin’s talks regarding arms contracts for Russia). Another offer made to the protagonist is also related to arms, that is machine guns. France’s defeat in the war with Prussia laid bare the technological inadequacies of the French army. Machine guns were a proposition researched intensively throughout the nineteenth century in several countries. The idea introduced to Wokulski by a mysterious acquaintance was not realised until 1883, but if we consider the specifications of the weapon on offer (firing up to 30 bullets per minute, whereas the machine gun designed by Hiram Maxim would later be capable of as many as 600 bullets per minute), we may interpret this as a likely, and historically accurate, prototype of the subsequent invention.

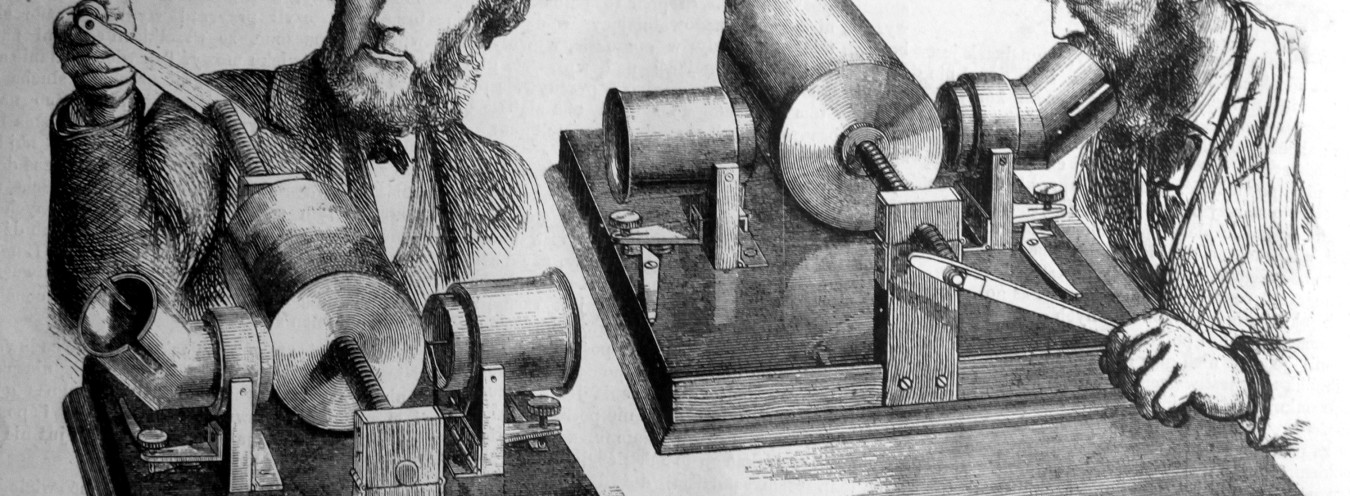

The French war with Prussia was an occasion to successfully test one more invention – the telegraph. It was patented in the early nineteenth century, but it was not until the second half of the century that its effectiveness was proven. Its use allowed the Prussian forces to attain a degree of precision and coordination which was previously unheard of. The telegraph in The Doll is presented in its everyday, non-military applications. Telegrams are meditated upon by Ignacy Rzecki – the speed with which they transmit information is, however, not judged too favourably by him as he complains about the tendency of the press to increase the speed of information and lose credibility. The telegraph and telegrams play an important role in the scene depicting Wokulski’s search for an excuse to leave the company in which he began the ill-fated journey to Kraków. In Skierniewice, the protagonist convinces the chief conductor to call out his name as the addressee of a message sent by telegraph.

The inventions that were hallmarks of the times described by the novel also contributed to the modernisation of the urban infrastructure. Wokulski’s first encounter with the modern metropolis of Paris takes place at the railway station, or to be more precise – under the station roof, made of great sheets of glass secured with a metal framework. As he travels through Paris, artificial lighting is mentioned: he notices the trees, lining the streets and boulevards, and equally straight lines of gas lamps alongside. The inventor Ochocki can boast an achievement which, like the telegraph, results from a practical application of electricity. The young scientist works on a model of the electric lamp and makes remarkable progress. The characters’ efforts are therefore presented against a historical backdrop of scientific research which led to the use of electricity in lighting: the 1878 Fair saw the first application of the arc lamp (to illuminate Place de l’Opéra), and next year Thomas Edison would patent his light bulb.

→ Professor Geist; → Paris and the World’s Fair; → Railroad; → Rzecki, Ignacy; → Ochocki, Julian; → Wokulski, Stanisław;