Railroad

The representation of the railway certifies Prus’s status as an insightful observer of daily life and a writer able to recreate the facts of communication and transport with expertise and remarkable attention to detail. A perfect example of this is the composition of the scenes which lead to the severing of ties between Wokulski and Izabela Łęcka. The romantic narrative finds its turning point while the characters are travelling on a Warsaw-Vienna Railway train. It is then that Wokulski hears a conversation between Izabela and Kazimierz Starski – held in English and concerned with Wokulski himself. The journey begins in a nervous atmosphere. In Warsaw, Starski arrives late at the railway platform – he misses the second bell, which signals that the doors to the carriages (as well as those leading from the station to the platform) will be closed soon. Tomasz Łęcki, of frail health, finds it impossible to entertain Wokulski with conversation for long. Soon after they leave Warsaw, he asks for the window blinds to be shut, the lights to be dimmed, and he falls asleep. After nearly an hour, the train stops in Skierniewice. The conductor opened the door. Wokulski leaped up. The moment at which the train stops looks dramatic mainly because the doors to the carriages on the Vienna Railway trains were opened and locked with a key – from the outside only. This was common practice on European railways, justified by security precautions: locking the carriage doors (signalled by the second bell, with the third bell signalling departure) was to prevent passengers from accidentally falling out of trains. It also meant, however, that while the train was on its way from one station to the next – where the conductors would unlock and open the doors again after the train stopped – the passengers were unable to change carriages or compartments, which as a result became isolated spaces, only accessible from the outside. The situation pictured in the Skierniewice scene is all the more vivid when we compare this interrupted Vienna Railway journey with another, earlier one, where Wokulski accepts the Duchess’s invitation to visit Zasławek. The details in the novel indicate that this journey was made on the recently opened the Vistula Railway (Nadwiślańska Droga Żelazna). It connected Warsaw to Mława and Kovel, and in the early months of 1878 (which is when The Doll’s plot begins), its passengers could commence their journeys on the newly-opened Nadwiślański Station, located directly next to the Warsaw Citadel. At first, Wokulski travels alone, watching the starry sky through the compartment’s open window. Soon, however, he is interrupted by a knocking coming from the corridor, and the “chief conductor” appears, informing Wokulski that Baron Dalski wishes to accompany him on the journey. Having agreed, Wokulski is joined by the Baron, who is returning from Vienna and also travelling to Zasławek. The two railways depicted in the novel differed in the way their carriages are laid out, and Prus takes advantage of this fact in his composition. He uses the strong feeling of being locked in the Vienna Railway compartment experienced by Wokulski to intensify the emotional temperature of his emotional response to Izabela’s liberties taken in her cousin Starski’s presence.

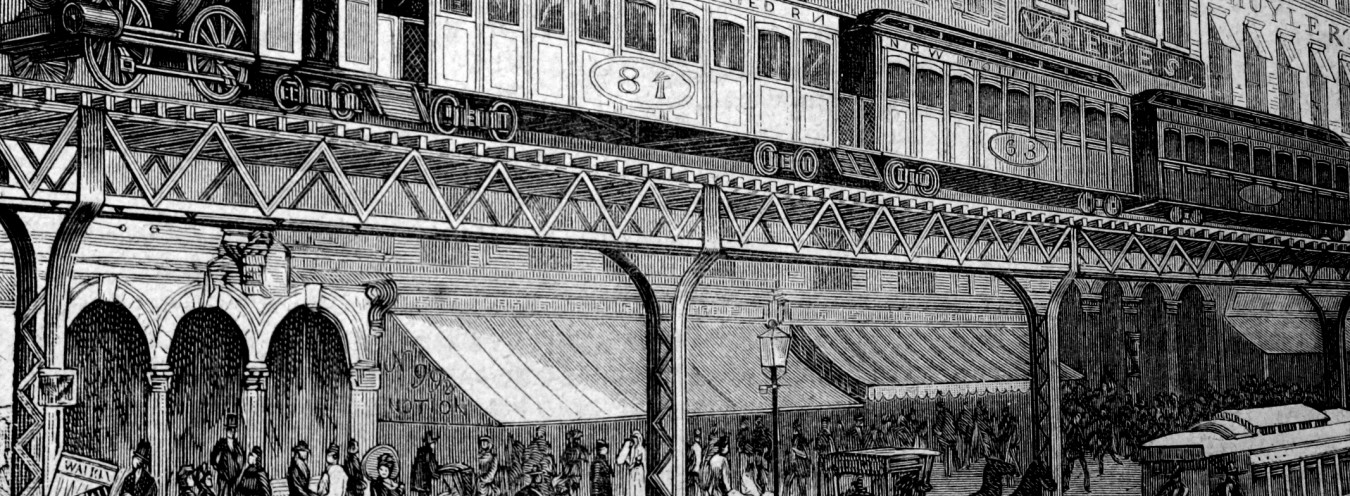

The railway map of the novel encompasses all routes in operation on the Russian partition territory of Poland. Two of them, the Warsaw-Vienna Railway (where Wokulski’s failed suicide attempt takes place) and the Warsaw-Bydgoszcz Railway (which the protagonist takes en route to Paris via Berlin), were designed to use the standard gauge, which facilitated Warsaw’s integration with the European railway network. The Vistula Railway, the Warsaw-Petersburg Railway (which Julian Ochocki takes as he travels to Petersburg on business relating to the Duchess’ will), and the Warsaw-Terespol Railway (which Wokulski possibly takes en route to Moscow) used the Russian gauge, thereby integrating the Russian Empire with those territories of Congress Poland which were on the Vistula’s eastern bank. Prus composes the scenes on the Vistula and the Vienna Railways differently, but he also uses a modification to the latter railway in his novel’s plot. Namely, according to hearsay reaching Doctor Szuman’s ears, Wokulski does not leave for Moscow in October of 1879, but he is seen in Dąbrowa instead, where he is rumoured to have bought dynamite. This town in the region of Zagłębie in the South-East of Poland is within the main character’s reach as – since 1859 – Dąbrowa has been a station on the Vienna Railway’s main route, leading not just to the border but all the way to Sosnowiec, which placed it in contact with the Prussian railway. Prus conscientiously notes various intricate details of the railway’s everyday use. He mentions the classes of carriages (he mentions two of them, and some trains had as many as four), the railway workers’ roles (station master, chief conductor, conductor, lineman, janitor), as well as the signalling (bells and lights on trains). The railway reality in the novel has one more ingredient: Rzecki enjoys spending his free time surrounded by toys, and one of them is a circular model railway track with a miniature train, complete with lead passenger figurines. These toy trains began to be produced in mass numbers in the 1870s, mainly in Germany, where the toy industry centred around the city of Nuremberg. The German wares could make their way to the stores of Nuremberg mentioned by Rzecki as he outlines Katarzyna Hopfer’s sizeable dowry. They also made their way, clearly, to Wokulski’s store.

→ The Trial for the Theft of a Doll; → Testaments; → Toys;