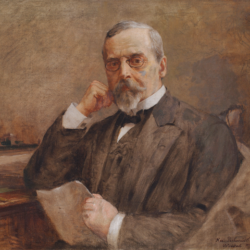

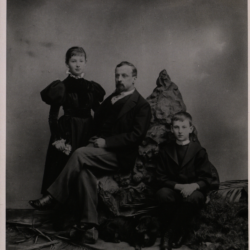

How to perceive Sienkiewicz?

“U Henryka Sienkiewicza” (Visiting Henryk Sienkiewicz), an eight-page long article by Ferdynand Hoesick, was the longest text in the Tygodnik Ilustrowany jubilee editions. It proves especially valuable for me as it is both a textual and a visual report on the interior of Sienkiewicz’s house. This article is heavily image-focused and can be treated as a tribute to the visual aspect of the writer’s lifestyle. Hoesick is describing what can be seen on pictures: a true horror vacui. The walls, the cabinets, and the desks are loaded with hunting trophies, guns, and bladed weapons, portraits and landscape paintings:

The whole room has a floor covered with a flowery carpet, door hidden behind a heavy curtain, drapes matching the crimson wallpaper; there is a big table in the middle, covered with a linen cloth, cluttered with books, trinkets, various writing utensils; a refined tiny desk bucking under the weight of ornaments, frames and curiosities stands between two windows; a fireplace glares from behind a Japanese screen, the mantelpiece is crammed with porcelain vases, bronze items, and photographs; an enormous ottoman supports the main wall; an array of soft, cushioned furniture is placed in the room in a tasteful manner; a glazed bookcase stands next to the door, tightly filled with decoratively bound volumes; on the walls – apart from several large and small shelves with books – lots of paintings, pictures, sketches, deer antlers and buffalo horns, animal skulls, old weapons, maces, karabelas, pickaxes, bows and Tartar arrows; a huge antlered head of a moose sticks out of one wall, placed high up; a beautiful, exceptional lamp from the East hangs from the middle of the ceiling.[1]

The reader who, seeking voyeuristic pleasures, had managed to get through such extensive descriptions, finally saw the writer’s study, in which Sienkiewicz created the very best of his works. Elaine Freedgood,[2] a specialist on the descriptions of Victorian interiors, could have described this room as full of “cavalcades of objects.” These objects were hanging in mind-boggling weaves and combinations, with heavy, patterned cloth in the background. A lamp from the Far East shed light on the Wild West paraphernalia intermingled with images of the Tartars. One image on top of another: the gifts that the writer received were placed in between his trophies – a true graveyard of animals that had fallen prey to the writer’s passion for hunting. In Hoesick’s text, detailed descriptions of further items – sculptures, portraits, and landscapes – are interspersed with Sienkiewicz’s casual comments on his aesthetic preferences (he held the Pre-Raphaelites in high esteem), the origins of particular things, and the relationships they had with his biography. In this manner, reader-attractive information about Sienkiewicz – such as his hunts and journeys overseas, described, for example, in his Listy z podróży po Ameryce (Portrait of America) – gained a physical existence, embodied in real objects. Next, these items-relics were offered to the newspaper readers in two ways: in Hoesick’s written reportage and in the photographs. The images are thus inscribed into an essentially modern pattern: the mass idol is being sold, and his private property may be subject to a harsh evaluation of the potentially critical audience. On the other hand, however, the reader denies this privilege and rejects the power which is granted to him with the ostensibly defenseless printouts of Sienkiewicz’s private properties. The social circulation I am investigating can thus be treated in a manner akin to the circulation of hagiographical writings, which tend to be accompanied with illustrations. Images of this kind provide an accessible idea of a hero, including his actions and typical characteristics. They are spread in order to cultivate and strengthen faith – and such is the case of the newspaper images I discuss here. One should not forget how strongly the images of Sienkiewicz and Poland were interrelated, and that, as a consequence, the writer was not the sole object of faith, but so was the idea of the nation-state that he represented.