EN-Warszawa zrusyfikowana (miasto przemilczeń)

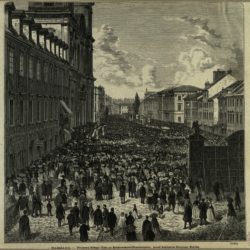

When read from today’s perspective, the columns written by Sienkiewicz in the 1870s to record, as their title suggested, “the present moment,” could be given a different title. They could be well summarized with the phrase “against all the odds.”[1] The writer’s journalistic texts were written in the period of the Russification of Warsaw, a process that covered also changes in architecture. Those took a variety of forms – from the conversion of individual buildings and changes in their functions (Łazienki Park, Belweder Palace), to the urban layout (transportation network, military buildings).[2] The conversion of key buildings into the seats of the Russian authorities, military barracks, and Orthodox churches,[3] the closure of schools and monasteries, the presence of Russian troops in clubs and in the streets, the construction of the Citadel and of the ring railway were, as we know, part of the social reality of the capital at that time. Marian Marek Drozdowski pointed out that “the Russian community in Sienkiewicz’s Warsaw consisted mainly of thirty thousand garrison soldiers,”[4] and “the system of Russian forts surrounding the city, together with the Citadel, hampered the city’s territorial and urban development.”[5] According to him, the places that were marked by the presence of the army included the Citadel with the nearby forts, the forts in the vicinity of the Vistula Railway Station and today’s Aleja Wojska Polskiego, and the forts in the area of Zielona Street, Powązki, in the districts of Wola, Mokotów, and Czerniaków. These forts – through a system of embankments and moats – were connected to the forts at the city borders. The treatment of Warsaw as a provincial town by Russian authorities and the lack of support of the decision-makers with regard to the city’s development are echoed in Sienkiewicz’s comments. These comments, which mainly concern the technical condition of the city, are an essential element of the description of its physical space. For obvious reasons, the narration does not directly refer to political issues, but it concentrates on the everyday functioning of the city, to a large extent on the topics related to the cultural, social, and artistic spheres. Life goes on as if “in a niche,” despite the limitations and oppressions it is subjected to. And this is the space that Sienkiewicz describes in his journalistic texts.

For obvious reasons, the traces of the invader’s activity visible in the tissue of the city (for instance, the architectural conversion of the buildings and the erection of new monuments[6]) were omitted from the literary images of Warsaw. They are absent from the journalistic texts of both Prus and Sienkiewicz, who focused on everyday life and cultural life of Warsaw citizens. They are also deliberately and meaningfully ignored in their literary works. Janusz Tazbir called this disregard for the symbols of Russian domination “a peculiar kind of disapproval.”[7] He referred to the observations of Jan Kuczawa and Stanisław Mackiewicz, who showed that as a rule, 19th-century literature did not notice Russians in the city.[8]

The columns show a world that is seemingly normal: business lunches, excursions to the countryside, parties in the parks, dancing balls, concerts, and performances all take place. To a large extent, apart from the topics connected with urban infrastructure and development, the writer comments mainly on social occasions, lectures, and charity auctions because cultural life goes on irrespective of – or rather despite – the limitations. And that is why Ferdynand Hoesick believed that Sienkiewicz’s involvement in “organic life” was an expression of a political attitude.[9]

In his columns, the takeover of the building for the seat of the commanding officers is described as something ordinary, and the stress is placed on the plan to allocate the rooms for cultural purposes. In 1875, Sienkiewicz wrote:

[…] We can again hear the news on the demolition of the ugly pavilions in Saski Square, and journalists – look at their fantasies – even write about the conversion of the building taken over for the seat of the commanding officers into a theater devoted to opera and ballet. In such a case, the Wielki Theater would house drama and comedy, and the Rozmaitości Theater would be turned into a comfortable concert hall.[10]

This strategy of ignoring the issues that evoked natural opposition in an obvious way became the part of the trend of “silent” writing, characteristic of the 19th century.[11] It is also a factor that needs to be taken into consideration in the analysis of the physical space presented in the columns. Texts are a testament to the experience of space; they are the carriers of information regarding its relations with society.

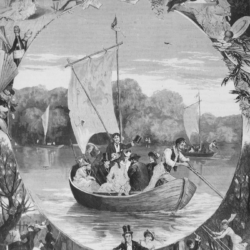

Focusing on the descriptions of the city, Sienkiewicz emphasizes the elements that are its natural components – he characterizes concrete social groups, calls for the support of the institutions, portrays the ambiance of the moment. Sienkiewicz reported, “We mentioned the old woods along the Vistula River; let us then speak now about the Vistula of today. The river is fickle, bound on its right side with a floodbank so it cannot play nasty pranks on the district of Praga, which it used to bathe in cold waters every year.”[12] When writing about Praga, he pictured the community of the riverside dwellers, whose place in the hierarchy depends on whether they own a boat and a fishing net. A group of homeless vagabonds lives next to them. In the summer, this area of the city becomes more vivid when the craftsmen take rides to Saska Kępa and use the services of the carriers. The pages of the articles conjure the images of the colorful crowds in boats, bathed in romantic lights, in the fog, at night, accompanied by the rafters’ songs, surrounded by the streams of sparks from the steamers, in the darkness and smoke. Summer performances are held in a garden near the Vistula (Antokol Theater on Praga Embankment) in the tents lit with kerosene lamps. When we leave the space described in the columns, in the vicinity of the river, a historian will notice Russian troops and forts, such as Sergei’s fort (in the area of today’s Żeromski Park – as pointed out by Drozdowski), or Vladimir’s fort on the right bank of the Vistula River.[13]

Przypisy

- I juxtapose this formula with the description of the-then Warsaw, presented in the Studia Warszawskie series [Warsaw Studies]: “The years 1795–1918 constitute a whole era in the history of Warsaw. […] It is sufficient to examine Warsaw at the moment of its fall at the end of the 18th century and to compare it with the city on the eve of the First World War. We can see the long road that Warsaw had gone through during those 120 years. The changes concerned all areas of the city’s economy as well as the social, political and cultural relations.” At that time, Warsaw was politically oppressed; it was being gradually deprived of the functions of the capital city, and it was degraded to a provincial town. Still, it preserved many features of a capital city” (Editor’s note, Warszawa XIX wiek, 1795–1918 [Warsaw, 19th century, 1795–1918], vol. 1, Studia warszawskie [Warsaw Studies] series, vol. 6, edited by. R. Kołodziejczyk, J. Kosim, J. Leskiewiczowa, Warsaw 1970, p. 5). All translations from Polish sources by Ewa Nowik.

- For more on this topic, see, for instance, P. Paszkiewicz, Pod berłem Romanowów. Sztuka rosyjska w Warszawie 1815–1915 [Under the Romanov rule: Russian art in Warsaw, 1815–1915], Warsaw 1991; M. M. Drozdowski, Warszawa epoki Sienkiewicza [Warsaw at the times of Sienkiewicz], in H. Sienkiewicz, Felietony warszawskie 1873–1882 [Warsaw columns, 1873–1882], selected and edited by S. Fita, Warsaw 2002.

- The most spectacular and painful blows to the population of Warsaw was the construction of Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Saski Square (today’s Piłsudski Square), the conversion of the Staszic Palace into Saint Tatiana of Rome Orthodox Church, and the conversion of the Royal Castle chapel into an orthodox church.

- M. M. Drozdowski, op. cit., p. 20.

- Ibidem.

- We can list here the Monument of Seven Generals, also known as the monument of the Poles who died loyal to their monarch (unveiled in 1841 in Saski Square – the place which for the Poles was also the symbol of shame), the monument of Paskiewicz in front of the Viceregal Palace or the monument of Tsar Alexander the First located in the Citadel.

- J. Tazbir, “Walka na pomniki i o pomniki” [The fight with monuments and about monuments], Kultura i Społeczeństwo 1997, vol. 1, p. 8.

- J. Tazbir, “‘Zdrajcy’ pomnikiem zhańbieni” [Traitors shamed by the monuments], Przegląd Humanistyczny 1997, vol. 6, pp. 23–24. Tazbir quotes the words published in the Wiadomości Literackie magazine: “Those people were skillful in remaining silent. This was a certain sad form of a protest” (J. Kuczawa, “Spiż, marmury i historia” [Red bronze, marbles, and history], Wiadomości Literackie 1938, vol. 52–53, p. 6. For the conspicuous absence of Russian traces in Lalka (The Doll) by Prus, see E. Paczoska, ‘Lalka’, czyli rozpad świata [The Doll or the fall of the world], Białystok 1995 (especially the chapter entitled “Warszawskie Elizjum”).

- F. Hoesick, “Przedmowa” [Foreword], in Sienkiewicz jako felietonista. Zapomniane kartki z teki Litwosa (1873–1883) [Sienkiewicz as a columnist: Forgotten pages from the portfolio], Warsaw 1902, pp. v–vi.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Chwila obecna [The present moment], vol. 1, in Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 48, edited by J. Krzyżanowski, Warsaw 1950, p. 27.

- In this case, I am interested in the purposeful omissions of political issues and of the traces of Russians in Warsaw only in the context of the representation of space. I do not undertake to discuss the theme of omissions of political reality in literary representations. This theme is the subject of study of the scholars examining positivism, especially the works of Bolesław Prus – see E. Paczoska, op. cit., L. B. Grzeniewski, “Warszawskie realia ‘Lalki’” [Warsaw reality in The Doll], in Śladami Wokulskiego. Przewodnik literacki po warszawskich realiach „Lalki” [Following the traces of Wokulski: A literary guide to Warsaw reality of The Doll], edited by S. Godlewski, L.B. Grzeniewski, H. Markiewicz, Warsaw 1957; B. Bobrowska, Małe narracje Prusa [Little narrations of Prus], Gdańsk 2004. For a different perspective on the issue of such omissions, see J. M. Rymkiewicz, “Nie ma Polski, nie ma Rosji, nie było powstania: Tygodnik Ilustrowany w 1863” [There is no Poland, no Russia, there was no Uprising: Tygodnik Ilustrowany in 1863], Gazeta Polska 2013, no. 1.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Bez tytułu (1873) [Untitled (1873)], in Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 47, Warsaw 1950, pp. 48–49.

- M.M. Drozdowski, op. cit., p. 20.