Statues and Monuments

At one end was King Zygmunt, standing on what looked like an enormous candle, inclined towards the Bernadine church as if he wanted to communicate something to the passers-by. At the other end, Copernicus, holding a motionless globe in one hand, turned his back on the sun which rose every day behind the Karas Palace, ascended over the Society of Friends of Art and went down behind the Zamoyski Palace, as much as to contradict the saying: ‘He stopped the sun – and made the earth rotate.’ (223)

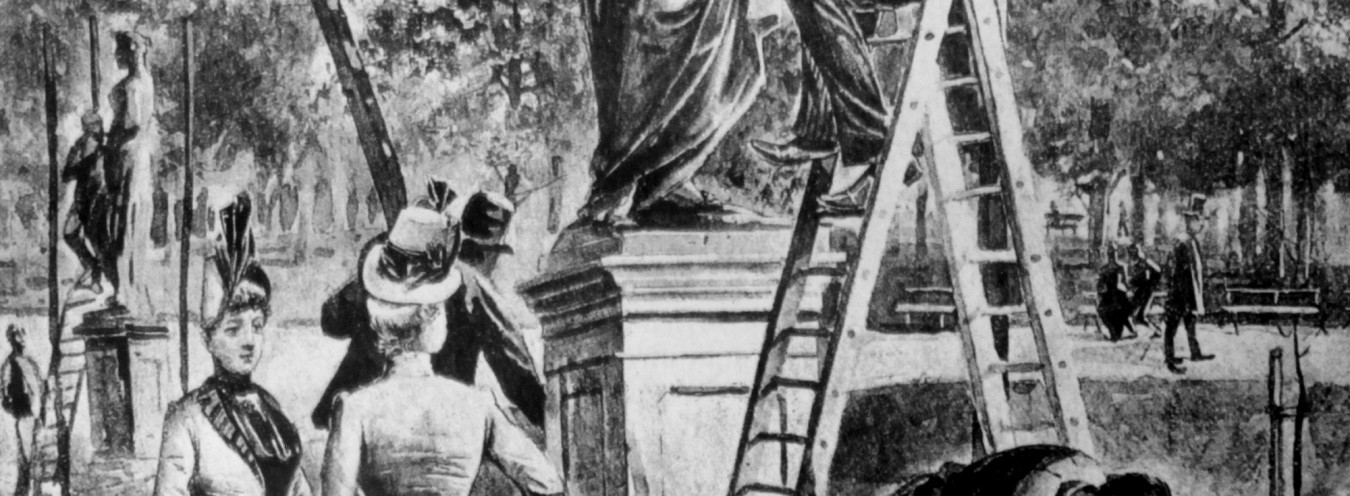

In the period covered by The Doll, almost all Warsaw monuments were situated close to the representative Royal Route. The statue of Zygmunt III Vasa (Sigismund III) stood atop a tall column in front of the Royal Caste, overlooking the city. The majestic Nicolaus Copernicus, sculpted by the famous Bertel Thorvaldsen, sat in front of the Society of Friends of Art building. A fine statue of King Jan III Sobieski, erected by King Stanisław August Poniatowski, stood further down the Route, in Agricola Street (today’s Agrykola), right in front of the entrance to the Łazienki park.

1870 saw the installation of the monument to the Tsarist Viceroy of the Kingdom of Poland, Ivan Paskevich, in front of the Presidential Palace. As Paskevich was commonly hated for the oppressions he imposed on Poles, and his statue stood between those of the respected Zygmunt III Vasa and Copernicus, there was a jokey poem about the former asking the latter: Why has this ass/Come between us? Paskevich’s monument was finally dismantled in 1917, and the equestrian statue of Prince Józef Poniatowski has stood on the site since 1965.

Just across the street, by Saski Square, Russian occupiers’ side during the November Rising. The famous statue of Adam Mickiewicz, which can still be seen today on Krakowskie Przedmieście, was unveiled a few years after the first publication of The Doll.

Prus himself was far from advocating the erection of any monuments. In his writings, he argued that their expense should be spared and the money allocated for social purposes such as schools, hospitals, orphanages. He was one of the few who openly opposed the initiative of commemorating the 100th anniversary of Mickiewicz’s birth with a statue.

The novel also features a memorial of a more sentimental nature: a gravestone that Duchess Zasławska asks Wokulski to commission for his uncle and the love of her life. It is supposed to be made of rock on which the couple used to sit in the ruins of the Zasław castle, with a few verses from Mickiewicz’s poem inscribed on it.

One cannot fail to mention a curious fascination of Izabela Łęcka with her marble figure of Apollo. The beautiful damsel owns a copy of the famous statue and spends her private time gazing at it in adoration. One day, the cherished idol seems to come alive and, from then on, he visits Izabela in her erotic dreams as a beautified version of her successive admirers.

In The Doll, references to monuments are often accompanied by ironic commentaries which censure the waste of money. However, they are all overshadowed by a scene that takes place in a chapel of the Holy Cross Church, where a Christ figure appears to Wokulski to lighten up at the sight of the approaching poor man. This illusion represents the change that has occurred in the protagonist since he entered the church with these thoughts in mind: What’s that huge building, which has towers instead of chimneys, in which no one lives, where only the remains of the dead sleep? Why that waste of space and walls; for whom does the light burn night and day; why do crowds of people gather there?