The bird’s eye view of the city

The physical space of the city as recorded in the columns includes not only images but also sounds, smells, and weather conditions. The pedestrian moves along the dust-covered streets, the uncomfortable cobbled roads, struggles with transportation problems, feels hot in summer and has to breathe the odors of the steaming gutters.

In the summer, when clouds of dust rise above the cobbled streets, filling our mouths and eyes, when our paths, devoid of water, start to emit an atrocious odor, when this odor combines with dust, smoke and hangs like a heavy leaden atmosphere above the city, then we can rightly say that Warsaw, which is called the paradise for the eyes due to the beauty of the ladies that live here and the purgatory for ears due to the number of barrel organs and pianos played by the talented ladies, that this Warsaw is hell for every nose that was not born here, has not lived here, has not been ill here, and has not been brought up here.[1]

Apart from sensual sensations, movement is an important element of the descriptions. It is the sign of the times – the reality of the 19th-century city, noisy, crowded, and bustling with life. An inhabitant of the metropolis misses the moments of peace and quiet, which can only be found outside the city borders.

And here is the city with its hustle and bustle, turmoil and hectic traffic, with crowds of people on the sidewalks and with glittering shop windows. You miss your dark, airy and clean retreat. I miss it too, and it is so difficult for me to return to the city […].[2]

This moment of refuge is possible thanks to the short time spent in the countryside or in the Botanical Garden, in non-industrialized zones (“God created the country and man created the town”[3] – the writer quotes a poet). There is also another attempt at a momentary escape from the sensory impressions experienced by an inhabitant of the city – noise, crowd, and stuffiness. Special attention should be paid to the spatial narrative strategy, which was employed several times in Sienkiewicz’s columns. This strategy consists in rising above the city level. It was used by the writer already in the first series of columns in 1873:

On the other hand, this life outside is boiling and bubbling in turmoil. The one who, having abandoned the stuffy city for a moment, could rise high, high in the clean evening air and look at the city from above, he would perceive this movement more spatially. From below he could hear the bustle and urban turmoil, in the dark corners and turns of the streets, he would see the crowds of people flowing in different directions. The gardens, where theaters and orchestras play, would look like shining lakes, where civilians, the military, and the dressed-up, made-up women, the ladies of the camellias. are visible in the waves of gaslight […].

But we doubt whether this winged wanderer would want to abandon his dark lonely airy highlands and would want to return to this sea of lights, to the stuffy streets with no sewerage system. He might prefer to fly over the silver ribbon of the Vistula, to forests, woods, and villages.[4]

This kind of halt is typical of the bird’s eye perspective, which was recognizable in the urban practices of the 20th century. The issue of the perception of the city has a rich theoretical background. The perception of the city as a labyrinth, as a text (unrecognizable or viewed from above) is linked to the realities in which particular ways of experiencing the space were becoming the most common (the influx of inhabitants to the 19th-century city, the status of a flâneur, the status of an individual against the crowd – different at the beginning of the 20th century from the one in a postmodern city of the 21st century). It is pointed out by Robert Tally, who juxtaposes Michel de Certeau’s postulates with Georg Lukács’s findings, thus contrasting the realist narration and the spatial experience of the walker with the naturalist description typical of a bird’s eye view of the distanced observer.[5] Tally notes: “It [the city] is both a text to be read (á la Bertrand Westphal’s notion of la géocritique) and a process of writing (as with Michel de Certeau’s discussion of ‘Walking in the City.’”[6] The important distinction is the one between (in de Certeau’s terms) “the practitioners of the city,” who walk its streets and create “the poem of walking,” and “voyeurs from above,” where the metaphor of the city ceases to function.

In the context of the spatial practices of the city, it is worth quoting de Certeau, who points to the bird’s eye panoramic view (looking at New York from the top of the World Trade Center – the view that is different from the limited perspective from the inside of the urban labyrinth. In the 1980s, de Certeau wrote:

To be lifted to the summit of the World Trade Center is to be lifted out of the city’s grasp. One’s body is no longer clasped by the streets that turn and return it according to an anonymous law; nor is it possessed, whether as player or played, by the rumble of so many differences and by the nervousness of New York traffic. When one goes up there, he leaves behind the mass that carries off and mixes up in itself any identity of authors or spectators. An Icarus flying above these waters, he can ignore the devices of Daedalus in mobile and endless labyrinths far below. His elevation transfigures him into a voyeur. It puts him at a distance. It transforms the bewitching world by which one was “possessed” into a text that lies before one’s eyes. It allows one to read it, to be a solar Eye, looking down like a god. The exaltation of a scopic and gnostic drive: the fiction of knowledge is related to this lust to be a viewpoint and nothing more.[7]

These words clearly remind us of some parts of Sienkiewicz’s columns, for instance:

We will go up some tower, for instance, the one in Saint Cross Church, and from its height, we will look down at the city. After all, it is the feast of Corpus Christi today. Down there, the city is closing in on our eyes, it is so difficult to breath; it is so boring, so sad![8]

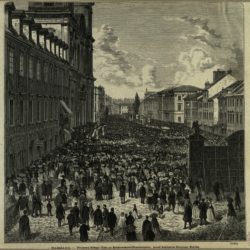

The 1875 celebrations of Corpus Christi, observed by Sienkiewicz from the tower of Saint Cross Church on Krakowskie Przedmieście Street, were also described by Bolesław Prus, who witnessed the events of that day in Grzybowski Square. The narration conducted by Prus from the point of view of the crowd concentrates on individuals and on individual practices. The crowd loses the features of a mass; the view from within allows us to see the details, actions, individuals, and events. These concrete elements build this fragment of the city. In the column from July 1-3, 1875, Prus comments on the events from the perspective of a participant and draws the reader’s attention to the absurd form of manifesting one’s piety by snatching the caps off Jews’ heads during the procession.[9]

In the description written by Sienkiewicz from the voyeur-observer perspective, the reader will find neither the detail nor the description of individual figures, but a panoramic view of all those gathered below. Focused on aesthetic impressions, the description is constructed by the commentator, who is distanced from the negative aspects of the city – the stinking walls, the clouds of dust and noise.

Sienkiewicz wrote:

Krakowskie Przedmieście Street, bent in an arch towards the Vistula River, runs beneath our feet. Everything is clear as day. Below us – Copernicus with a globe in his hand, looks up, as if longingly, farther on – terraces of houses, and farther down, at the end of the street, King Sigismund, with a sword and a cross, barely visible from a distance. Today is the feast of Corpus Christi so there are altars in the streets; you can see the whole line. Dressed in flowers and greenery, they seem like May islets. There is a huge crowd of people At their feet, rocking slowly, expanding and growing in strength with every minute.[10]

Despite the continuous industrial development, Sienkiewicz’s Warsaw is a provincial city, still backward, struggling with the issues of roads, water supply system, and street lights. Looked at from the perspective of the street, the city is squalid, facing transportation problems, grey and unfriendly because its development is not supported by the authorities. Other writers of that period also depict Warsaw as a behemoth city, dark and mysterious.[11] Thanks to the distance, the view from above offers a different impression, and in the end, Sienkiewicz concludes:

[…] everything starts to take on the usual urban color, not too charming or poetic. But let us not leave, at least for a moment, our airy highlands. It must be so good and beautiful here in the evening. From there, we can see not only our stinking walls, our tollbooths, our provincial quarrels and storms in a teacup. There, the horizon is broader; the atmosphere is brighter. […] I have to go down, to the dark and stuffy streets of our city.[12]

Vertical orientation in the image of the city can also be found in other texts from Sienkiewicz’s era (we can mention the most recognizable description of this type – the image of Paris in The Doll by Bolesław Prus). Still, the bird’s eye view is not always connected to the convention of distancing and opposing the participation in the “urban crowd.” It helps create another important 19th-century model of the city next to the labyrinth: the panorama. Here, the juxtaposition of the perspectives used by Sienkiewicz and Prus when reporting the celebrations of Corpus Christi emphasizes the spatial strategy of the bird’s eye view employed by the former in his columns. Moreover, this strategy is motivated by Sienkiewicz’s desire to escape from the busy city.[13] Faced with the realities of Warsaw at the end of the 19th century, Sienkiewicz resorts to the perspective of Icarus, the perspective contrasting with the limited perspective of the pedestrian, who is overwhelmed by urban surroundings in all their aspects: visual, audio, and olfactory. It seems that the inhabitant of Warsaw in the late 1870s cannot take a stroll (his legs get twisted and his shoes get damaged on broken cobbles), he cannot admire shop windows (due to the clouds of dust and the stuffiness prevailing despite the citizens’ requests to use road sprinklers and to build a sewerage system). He cannot admire the metropolis while taking a horse-car (since both the horses and the cars are in poor condition). Thus, the reasons for getting up and away from the crowded city are completely different from those that drive the 20th-century inhabitant of New York in Walking in the City – the inhabitant of a modern city, overwhelmed with the pace of life and the excess of stimuli. Seemingly, both the former and the latter want to look at the city from above in order to escape its hustle and bustle. Still, the voyeur from the 20th– and 21st-century metropolis seeks the perspective that would not be limited by the urban labyrinth, and he does that in order to leave down there “the mass that carries off and mixes up in itself any identity of authors or spectators.”[14] By this, he resigns from the participation enjoyed by “the practitioners of the city.” The Warsaw-dweller’s desire for the ascent the depicted in Sienkiewicz’s columns stems from the fact that down there, “the city is closing in on our eyes, it is so difficult to breath; it is so boring, so sad!”[15].

Przypisy

- Ibidem, p. 127.

- Ibidem, p. 130.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 47, p. 89.

- Ibidem, pp. 88–89.

- R.T. Tally Jr., “Neutral Grounds, or, The Utopia of the Urban,” The Journal of Contemporary Literature 2010, pp. 134–148.

- R. Tally, op.cit. Elżbieta Rybicka calls these two opposing perspectives presented by de Certeau the conceptual city (rational functionalism and the product of urban theories) and the experienced city – the point of view of a pedestrian. See E. Rybicka, “Geopoetyka (o mieście, przestrzeni i miejscu we współczesnych teoriach i praktykach kulturowych” [Geopoetics (about the city, space and their place in the contemporary cultural theories and practices)], in Kulturowa teoria literatury. Główne pojęcia i problemy [Cultural literary theory: Key concepts and issues], edited by M. P. Markowski, R. Nycz, Kraków 2002, p. 474.

- M. de Certeau, “Walking in the City,” in The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by S. Rendall, Berkeley 1984, p. 91.

I evoke here the 20th-century theories in order to point out that some phenomena that were characteristic of the modern and postmodern city contain elements that had already been signaled in the 19th-century perspective. The bird eye’s view, which can be found in Sienkiewicz’s journalist texts, became popular thanks to works such as Michel de Certeau’s Walking in the City (1984), These issues are connected with cognitive mapping and cartographic modeling of space focusing on landmarks (see K. Lynch, The Image of the City, Cambridge 1960; K. Schlögel, In Space We Read Time: On the History of Civilization and Geopolitics, translated by Gerrit Jackson). The work of de Certeau has been quoted in the part of this paper devoted to physical space because the elements of this perspective can be found in Sienkiewicz’s narrative strategies, and secondly, because it is connected with the issue of landmarks indicated by the writer on the cultural map of Warsaw.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 48, p. 166.

- B. Prus, Kroniki [Columns], edited by Szwejkowski, vol. 2, Warsaw, 1957, pp. 66–67.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 48, p. 166.

- See also Warszawa pozytywistów [Warsaw of the Positivists], edited by J. Kulczycka-Saloni, E. Ihnatowicz, Warsaw 1992.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 48, pp. 167–169.

- Compare S. Fita, “Warszawskie felietony Sienkiewicza” [Sienkiewicz’s Warsaw columns], in H. Sienkiewicz, Felietony warszawskie 1873–1882 [Warsaw columns, 1873–1882], edited by S. Fita, Warsaw 2002, p. 12.

- M. de Certeau, op. cit., p. 191.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 48, p. 167.