The view from the city level (industrial aspect)

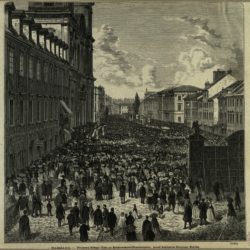

Researchers point to Sienkiewicz’s interest in the technical condition of the city – street cobblestones, lights, the issue of the water supply system. As early as 1882, he wrote about problems related to the poor infrastructure and the unrealized Lindley’s sewage system project.[1] A map of the most frequented and most inaccessible places due to the poor quality of the streets emerges from the descriptions of public transportation. It is not only a map of objects and the street network but also a plan of the places where city life is most vibrant. The Castle Square is an area where transit vehicles accumulate, whereas rumors have been circulating about the widening of Wierzbowa Street “by demolishing the annex of the Brühl Palace” etc. Apart from information about the theater building, about the development plans for the most representative buildings, there is also the issue of dirty trams (“there are no worse vehicles in the world”[2]), congestion and mud on the main streets, narrow roads, cobblestones, and railways. The author takes up the subject of planned and never implemented communication and sewage system improvements, all the way to the issue of dirty water in the Vistula River – “in no European city was the sewage system so widely discussed and nowhere was so little done about it.”[3] The search for the places worthy of cultural events is constrained by the technical condition of the facilities. In urban planning, there is a visible lack of consistency both in terms of architecture and decision making. Nevertheless, the city is being developed (for example, the writer reports an accident near Pawia Street, where three newly built houses collapsed onto the construction workers). A lot of space in the columns is dedicated to the subject of Warsaw public transportation (“It is said in Warsaw, and even written and printed, that a certain railway official has invented a new machine that is to replace today’s steam engines and that is set into motion by means of a crank”[4]) – both on a wider scale and at the city level. However, the bipolarity of the phenomenon is visible here as well, since the intensive life of the city is hampered by the shortcomings of its communication system:

It is one of the unique features of Warsaw that the most frequented streets are the narrowest. Senatorska Street from Teatralny Square to Sigismund’s Column, Wierzbowa, Żabia, and Graniczna Streets are the main routes of urban traffic, where all the carts, carriages, and wagons carrying wood, drag with countless stops. For the inhabitants of Warsaw who must pursue their affairs in those streets, it is almost impossible to cross.

[…] all wheeled transit transports through Warsaw should be informed about the streets which they are not allowed to use; as for the wagons and carts collecting or discharging their loads in the city, they should be instructed to keep sufficient distance between one another for passing or crossing […]. Since it often happens that there are up to forty wagons in a continuous line on the street turn […].

The worst point is undoubtedly the stretch of Senatorska Street from Miodowa Street to Sigismund’s Column. There are always loads of carts, wagons, trams, and carriages; sometimes you will have to wait for a quarter or even half an hour before you can get through. When planning a new urban communication network, would it not be more reasonable to extend Miodowa Street to Krakowskie Przedmieście than to create Włodzimierska Street, which is used only once a month? [5]

The image of Warsaw in Sienkiewicz’s columns from the 1870s consists of the descriptions of transport routes and important buildings, the representation of which is triggered in the context of events. These events are often determined by external factors:

The river overflowed the banks, especially on the Praga side. The houses in Praga, hidden behind the protective embankment, seem to look with irony over the embankment at the waves, so disastrous and terrible for them in the past. Praski Park is almost halfway under water, which got in between the alleys, dense willows, juniper, creating as if still, murky, but calm lakes. Saska Kępa is also almost completely underwater. Here, the eyesight gets lost in these huge, blue pools of water that have flooded vast areas.[6]

Crowds of people watching this view gather especially in the area of Nowy Zjazd and on the bridge. That sets out another plan pointing to the vertical layout of the city.

Przypisy

- The implementation of the Lindley’s water and sewage project began in 1883, but it had been awaiting approval from St. Petersburg since 1879. See F. Kucharzewski, Wodociągi i kanalizacja w Warszawie. Projekty dawniejsze – projekt Lindleya [Water and sewage system in Warsaw: Older projects. Lindley’s project], Warsaw 1879.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 47, p. 27.

- Ibidem.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 49, p. 104.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Dzieła [Collected Works], vol. 48, pp. 25–26.

- Ibidem, pp. 107–108.