American Indian Wars

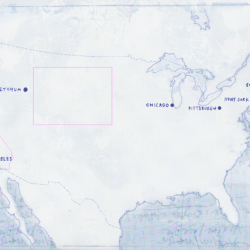

Finally, we have the unique experience of the frontier war described on the pages of the Trilogy. The time between 1875 and 1877 represented the most important and decisive period in the war with Native Americans to colonize the West, both the South-West – formally obtained, like California, after the Mexican-American War but in fact constituting Indian country belonging to the Navajo, Apache, and Comanche – and the North-West, constituting free territory inhabited mainly by Indian tribes (esp. the Sioux).

By and large, it is difficult to clearly mark the beginning of the war with Native Americans, especially in the South, where the state of war between the settlers and the Indian tribes, notably the Comanche, was permanent and for 40 years had gradually escalated with the increased colonization.[1] It must be borne in mind that it was an undeclared war, with periodical involvement of the US army or local volunteer forces in the South, but it nevertheless remained a permanent state and encompassed everyone. The military presence markedly increased in the 1850s and did not cease with the Civil War. To the contrary, since 1861 (1862 in the Northern territories), it transformed into organized military action even though, for obvious reasons, it was often led by the militia, volunteer, or auxiliary forces. Therefore, the decision of the Congress and the United States Army to take massive military action against Native Americans was not so much a reopening of hostilities as an attempt to bring some order into the war or to finally subdue the indigenous tribes. It was supposed to be achieved with the help of the units battle-hardened in the East, and among them, often, officers who had fought Native Americans before the Civil War.[2] It must be added that it was a failed attempt. The war against the Sioux waged in the North (usually called “Red Cloud’s War,” especially in reference to the period between 1867 and 1868) probably sparked the most public interest, and it was groundbreaking in terms of narration as it was probably the first time the American public started regarding Native Americans as thinking opponents, not a force of nature. It ended in 1868 with a truce that satisfied neither party.[3] The peace, which in the northern territories formally lasted until 1875, was, in fact, a state of permanent tension between the actions of the settlers (mainly building railways and roads to the western coast) and the firm resistance of the Sioux, resulting from time to time in Indian assaults on the civilians and minor armed conflicts. Larger confrontations were avoided mainly because the activities of the colonists were not that robust. The relative peace in the North allowed a more intense action against the unvanquished Comanche in the South. The military campaign against them, ongoing since 1867, gained more momentum only in 1871 and was not that successful at first. A permanent victory was achieved by the 1873-1874 campaigns, which finally closed in 1875.[4] The Apache war had a much less strategic value as their territory was remote and the conditions for settlement unfavorable (the rocks and deserts of present-day Arizona and New Mexico), and yet it was singular in its exceptional cruelty, even if compared to the appalling deeds committed on other territories. It continued from 1872 and reignited in 1879. For all intents and purposes, the period between 1872 and 1879 in the South could hardly be called a time of peace, not even a tentative peace as the one achieved in the North[5].

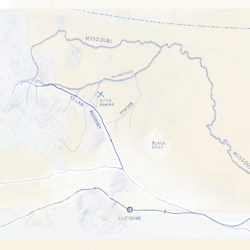

The Comanche were vanquished and now the Sioux war (the immediate cause of which were the deposits of gold found in 1874 in the Black Hills by a military expedition led by Col. George Armstrong Custer) found its dynamic climax between 1875 and 1877.[6] The country in its entirety focused at first on several spectacular American defeats in the spring and summer of 1876, especially on the battle of Little Bighorn, which took place on the Sioux territory (the present day borderland between the states of Montana and Wyoming), and then on the American counteroffensive in the fall of 1876 and spring of 1877, which drove the majority of the Sioux forces to surrender to the US or retreat to Canadian territory.[7] Sienkiewicz arrives in America a few months after Little Bighorn, at a time when the carnage of Col. Custer’s battalion is still a returning topic in the American press headlines. He follows the next stage of the war effort mainly as a reader but it is the plot and narration that is at the center of American life at the time and is of vital importance for California in particular as its further development depended heavily on an efficient and functional connection with the East of the country (which was the exact problem the organized colonization of the Wild West was supposed to solve).

Finally, probably in October 1877, the writer goes bison-hunting on the Wyoming territory. Admittedly, the war effort is almost finished after the key events of May, when Crazy Horse surrendered to the US forces and Sitting Bull, in charge of groups of loyal Native Americans, escapes to Canada (quite possibly Sienkiewicz and his companions would not have dared travel there otherwise), however, the memory of the recent events is still fresh and their traces still palpable. Sienkiewicz never came into direct contact with the war, but he could sense the aura, see the American troops still stationed in Wyoming, and finally, he could hear the narration of war in a place which, admittedly, had not been on fire itself, but was very close to what recently had been the front line. That is, of course, if he was really there, which shall be discussed presently.

Przypisy

- Compare Robert M. Utley, Frontier Regulars: The US Army and the Indians, 1866–1891, Bloomington 1977 (1st edition, New York 1973), pp. 44–58; pp. 111–115.

- Ibidem, pp. 44–58.

- Tom Clavin, Bob Drury, The Heart of Everything That Is: The Untold Story of Red Cloud, An American Legend, New York 2013, pp. 303–366; Robert W. Larson, Red Cloud: Warrior-Statesman of the Lakota Sioux, Norman, Oklahoma 1997, pp. 74–104.

- Compare S. C. Gwynne, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, Scribner, New York 2010, pp. 222–287.

- Compare Donald E. Worcester, The Apaches: Eagles of the Southwest, Norman, Oklahoma 1979; Edwin Sweeney, From Cochise to Geronimo: The Chiricahua Apaches, Norman, Oklahoma 2010.

- R. Utley, Frontier Regulars, pp. 243–245. See also Robert M. Utley, Sitting Bull: The Life and Times of an American Patriot, New York 2008, pp. 174–233.

- Compare R. Utley, Frontier Regulars, pp. 245–283; R. Utley, Sitting Bull: The Life and Times of an American Patriot, pp. 174–233; Philip Weeks, Farewell, My Nation: American Indians and the United States in the Nineteenth Century, Chichester–Oxford 2016 (1st edition, 1990), pp. 246–267.