Did Sienkiewicz ever go to Wyoming?

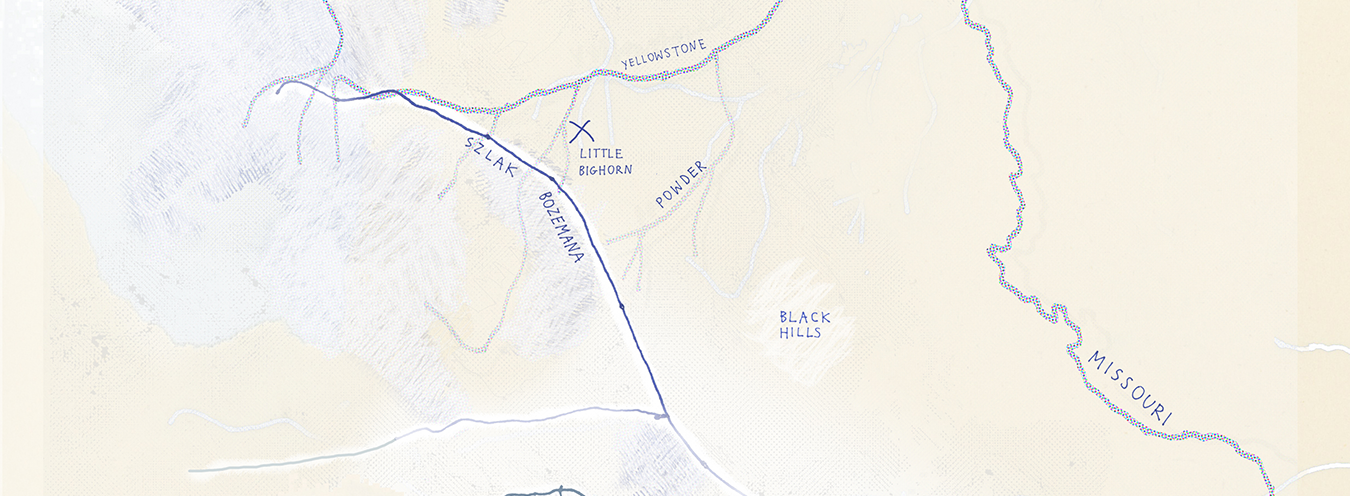

Did Sienkiewicz really go to Wyoming? The question has been asked by Jerzy R. Krzyżanowski, who disputes the authenticity of Sienkiewicz’s account and forms the thesis that we are dealing with an exquisitely forged piece of literary fiction.[1] Krzyżanowski’s argumentation follows two trains of thought. Firstly, he questions the probability of the entire situation. He points out that the travel companions are treated sketchily and stereotypically, their biographical data is difficult to define, and finally, it is improbable for Sienkiewicz to receive an invitation to participate in an expensive expedition for free. Secondly, he questions the details of the description which lead one to believe that a usually precise Sienkiewicz described a slightly different natural environment from what he could have experienced in that place and at that time of year. One must agree that the lack of a precise description in that part of the text really does pose serious difficulties. It is, after all, questionable whether a bison hunt was possible in the fall of 1877, that is, immediately after their mass massacre between 1872 and 1874, when their population perceivably dwindled until they were close to extinction, especially in the Eastern part of present-day Wyoming, the outskirts of the so-called great bison belt.[2]

One cannot then exclude the possibility that Sienkiewicz’s text is a compilation of accounts he had read and heard over the years supplemented by his gift of narration. Can the thesis be defended, however? That is impossible as well. Actually, every single argument cited here can be countered: Sienkiewicz could, after all, have been wrong when he was describing nature in a region completely unknown to him; he could have embellished his account with the stories from hunters who have hunted there in the past (which is, after all, quite a usual thing in hunting stories, especially those of a failed hunt; it is, in fact, the number of hunting failures in his later accounts from Africa that reaches an unusually high count); he could also have been concealing the personal details of his companions and the true circumstances of the expedition: employing a mask would be nothing unusual in this case. Something else, however, is much more important.

Whether Sienkiewicz visited Wyoming or not is actually of secondary importance. Obviously, if he was there, he could have, while processing his experience of war on the borderland, make good use not only of close relations but also of personally getting acquainted with the places where the war effort occurred and hearing the stories. Then again one could only talk of approximation as he never stayed in the military zone and spent most of his time on the territory of the Ute people, who had led a rather peaceful life in their reservations since 1872 and raised their weapons against the white man only in September 1879.[3] Arguably even a short stay in Cheyenne and the possibility to see the cavalry troops stationed not far away would give the second-hand descriptions much more color. Regardless, however, of whether the description of the journey to Wyoming is an account or a compilation, its very existence in the text bears witness to the importance of wars with Native Americans to Sienkiewicz. Regardless of whether he had set foot in the terrain or not, he should have been there. The wars with Native Americans constitute, for all intents and purposes, the compositional framework of Portrait of America. One of the first excerpts written after the arrival in America addresses Custer and Sitting Bull.[4] Undoubtedly, the events taking place in the West are those that focus the writer’s attention most of all. The most important things of all America are happening there. Sienkiewicz seems fascinated with the expansion of the States, the will to victory, the heroism of the cavalrymen fighting in the vast stretches of the wilderness, as well as with Native Americans. The victory of Sitting Bull over Custer, the way it was possible for the leader of a bunch of “savages” to defeat the well-trained cavalry. At the time, it was a source of amazement and fascination not only in American society. The journey to Wyoming is, compositionally and thematically, the only possible completion to Portrait of America.

Przypisy

- J. R. Krzyżanowski, “Sienkiewicz w Wyoming, czyli “trick or trip”? [Sienkiewicz in Wyoming: Trick or trip?], Pamiętnik Literacki 1996, vol. 4, pp. 65–75.

- S. D. Cashman, op. cit., p. 267; compare P. Weeks, op. cit.

- R. Utley, Frontier Regulars, pp. 322–344.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z podróży [Portrait of America], p. 110.