EN-Przestrzeń i społeczeństwo

Thanks to Foucault, the 20th century became, as researchers point out, the era of space. Edward W. Soja emphasizes that Foucault added space as a third element to the dichotomy of history-society.[1] Contrary to the belief concerning the dominance of the historical aspect at the time, Sienkiewicz’s writings from the late 19th century employ the space-society scheme. Although the writer is interested in the activity of institutions, the level of scientific and artistic events, every activity is closely related to or triggered by its location. His irony-based poetics uses an element of self-criticism, the narration refers to a collective subject, but this witty reflection on the mental structure of the city’s inhabitants surfaces in a specific situation, in a specific place. The place becomes the trigger, activating or exposing certain patterns of behavior. Some places “are attended,” which does not mean that the attending people do not fall asleep on literature readings, do not leave the theater during performances, or do not compromise themselves during balls and sports events. According to Zimand:

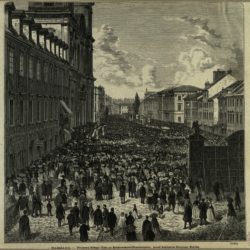

One of the important problems of the cultural model of modernism was the emergence of completely new cultural needs of very diverse social classes. With huge differences in financial situations, in the face of the existence of various types of economic, class, cultural, social barriers, etc. the pressure of the so-called social bottom on the sphere of culture was becoming increasingly more noticeable. Despite the social barriers, the first signs of the shortening the distance were appearing, for instance, in the form of sports competitions attended not only by the “social crème” but also by “the commoners” and, of course, these signs were criticized by the intellectuals of that time. [2]

The reaction to this particular cultural problem appears in Sienkiewicz’s journalistic texts. The imitation visible in the attempt to transform Polish nobility into English lords, the French language used during social meetings, drinking alcohol in the vestibule of the ballroom, entering the theater in the middle of the first act and leaving in the middle of the last act, etc., all these customs show the arriviste mentality of “the recently promoted presidents, directors and newly cultured families.”[3] This picture is complemented with business travelers for whom the ritual of “breakfasts” and cigars is a regular component of their stay in Warsaw (“Breakfasting is an outstanding feature of city life in Warsaw; it has no equals”[4]).

Physical space activates the imaginary one, with all its drawbacks and shortcomings. Sienkiewicz’s narration is based on similar rules, which makes it possible to evoke Foucault’s conclusions (which, after all, concern the 20th century) and thus leads to the reflection that the beginnings of the phenomena concentrated around the meaning of space crystallized already in the late 19th century. Particular topics raised in the columns (for instance, the Gas Association, sewerage system problems, street lights, flooding, etc.) lead to spatial creations. Starting with a specific physical area, the writer activates the social context in the reader’s imagination – the city is deserted in summer, bustling and crowded in winter. He activates a wider spatial context – the association with a seaside landscape.