The world of borderland cavalry

What was the world of the borderland cavalry at the time directly preceding the arrival of Sienkiewicz in America? It would do well to remember that, contrary to the frequently recurring opinions, the cavalry troops of the United States were not formed – or at least not mainly and not solely – of men who did not match the usual army standards or caused too much trouble and were thus sent to fight the Native Americans.[1] There were, of course, men like that, too. Nevertheless, the fact of “not matching the usual standards” means something slightly different. It is no accident that the new phase of American Indian Wars, which can now be called an organized war effort of the United States against the Native Americans, breaks out shortly after the end of the Civil War. The obvious consequence of the Civil War was the exorbitant number of high ranking officers, often quite young men who had quickly been promoted during the four years of war. What could the United States army do with such a large number of colonels and generals? They could not very well be demoted; simultaneously their military rank could not be maintained. As a result, a double rank system was introduced: the formal and the brevet system (George Armstrong Custer, for example, achieved the formal rank of a captain[2] but in the brevet system he was awarded the rank of major general). The war in the West theoretically was an excellent opportunity for the officers to achieve their military ranks once again, this time through a promotion during a regular war.[3] In effect, due to the limited number of positions within each rank, this was not so simple – sometimes the officers had to wait ten years or more for promotion.[4] This was a way, nonetheless, to provide the young men who were often unwilling to take their uniform off after the war, and having been taught to fight in the unprecedented, drastically cruel conditions of the Civil War, they found it difficult to perform any task other than the total annihilation of the opponent. The officers sent to the West were often those who were the most effective during the Civil War precisely because of their ruthlessness in fighting the enemy who was now again their compatriot. It was decided then to put their unusual skills to good use in fighting an opponent appropriately savage and vicious,[5] at the same time it was hoped that their meritorious contribution in the West would help to blur the memories of their recent actions in the South. This concerned first and foremost the commanders in chief, Generals William Sherman and Philip Sheridan, but also the not insignificant number of their subordinates, including the previously mentioned Custer.

The circumstances of the fighting in the West made the cavalry’s fate a ready material for a novel. After all, turning the events of the prairies into a cheap adventure romance was a common practice already at the time of Kit Carson, that is, from the early 1850s. Since Frémont’s report, all types of memoirs, expedition accounts, or battle narratives were also hugely popular. It was not uncommon for officers to publish their (often embellished) armed conflict adventures in the press; Custer is, again, a great example as in 1874 he published his collected press contributions as a separate volume entitled My Life on the Plains. A traveler fascinated with the West could therefore choose from a varied offer of printed material.

Three cavalry biographies are particularly worth mentioning at this point as they seem quite close sometimes to the life events of the characters of the Trilogy. Custer is incontestably obvious here.[6] Sienkiewicz, whose stay in the US falls almost immediately after Little Bighorn, must have known all the narratives about him; the Custer question was one of the most important topics at the time. What is important, the process of creating a hero and a martyr out of Custer, associated mainly with his widow’s tireless fight to make him remembered, begins a little later; it does not come into full force until the 1880s. During Sienkiewicz’s stay, there was no lack of critical opinions of Custer, specifically in the community that in the late 1860s tried to enforce Grant’s so-called peace policy, which aimed at the coexistence of white people and Native Americans, although, of course, within the framework set by the white race.

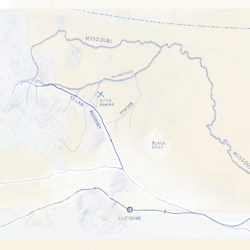

An officer with a borderland warlord mentality, throughout his entire military career specializing in the effective command of wanton hordes and in fact unfit for any other type of action, a born carouser and duelist, suspended from service and returned to duty multiple times, with an atrocious record from the Civil War, a martyr for the national cause, finally blessed with some happiness, though to a much lower degree than Kmicic (Kmita), for instance – the existing narrations of Custer were a ready-made prototype for the Trilogy character. From start to finish, this is a biography of a warlord – Custer’s first success during the Civil War was connected with effective pursuit actions in small cavalry regiments,[7] later on, he became infamous for his acts of suppression of civilians in the Shenandoah Valley. The defeat of Little Bighorn resulted from a failed attempt to destroy the opponent with a lightning-fast raid against the high command’s orders. Custer’s defenders pointed to his heroic stance at Gettysburg and his overwhelming victory over the Cheyenne at the Washita River (November 1868) during the American Indian Wars and the respect he gained among them. His opponents emphasized how he lost this very respect because of his numerous transgressions,[8] his breaking of rules of honor, too pronounced even for the permissive standards of the Indian war (mostly women and children perished in the battle of the Washita, it was also most probably Custer who attacked the peaceful group of the Cheyenne people[9]), or the incident bordering on treason in the summer of 1868 when Custer was AWOL. The theme of a reaver, traitor, and hero martyred by the barbarians is one of the American themes that abound in Sienkiewicz – and actually a raw material ready for use in a number of threads and characters in the Trilogy, not just Kmicic.

The profile of Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie could be a similar type of literary material, he was an officer whose entire career ever since they went to West Point together was connected with Custer and who was in many respects the very antithesis of the Little Bighorn commander.[10] S. C. Gwynne, a modern-day popularizer of the history of the West, wrote that Mackenzie was usually dispatched to bring order to the chaos that Custer had left behind.[11] The pattern did not vary after Custer’s death at the Little Bighorn, where Mackenzie became one of the most important commanders leading the counterstrike against the Sioux. Earlier, between 1871 and 1874, he played a decisive role in subduing the southern Cheyenne and the previously undefeated Comanche. Contrary to Custer, he carefully analyzed the way Native Americans fought and drew conclusions that were key to success. Similarly to Custer, he was a born swordsman, and despite his meager body of fragile build,[12] known for his unusual resilience to tiredness and pain, characterized by exceptional moral rigidity. Clearly self-fashioning himself as a Christian knight, Mackenzie closely reminds of at least two Sienkiewicz’s protagonists – Wołodyjowski and Skrzetuski. His presence was much less felt in the press than Custer’s (partially because of his unapproachable personality, partially because he was disinclined to advertise his adventures in writing), nevertheless, his ascendancy in the West had reached such great stature that he must have been known to any traveler interested in the West.

The third person worth evoking here, not so much to prove the influence of their biography on the creation of the Trilogy characters as to show the affinity between them, that is between the American experience and the processing of the memory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth borderlands – is Lieut. Gustavus Doane. Doane was one of the few white people who became famous as commanders of Indian scouts.[13] Two things differentiated him from the others. Firstly, throughout the 1870s, Doane, subsequently forgotten in the legend of the West, was particularly active in the press. His descriptions of the Yellowstone riverbanks exploration strongly contributed to the foundation of a national park at the location. Secondly, Doane was the man in command of the Crow Indian scouts who saved the survivors of Major Marcus Reno’s troops from the Little Bighorn massacre and recovered and buried the remains of Custer.[14] If we were to search in the West for close relations of Sienkiewicz’s Polish and Lithuanian officers in command of Tatar troops, it is Doane, in particular, that we should remember as he was the most famous among the commanders of Native American troops at the time.

Is it possible to speak here of prototypes of the protagonists of the Trilogy? That might be an overly far-reaching thesis. I would prefer to call that phenomenon finding confirmation of historical tales and sources in reality. Would Kmicic leading a troop of Tatar scouts ever come to life without Gustavus Doane commanding Native American troops? Possibly. Doane could have been, however, proof of the existence of a Kmicic for Sienkiewicz. And this is already a lot.

Przypisy

- Compare R. Utley, Frontier Regulars, pp. 80–92.

- From 1866 till his death, he served in the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

- Taking into consideration that the vast majority of Native American territory formally did not form a part of the United States but constituted its protectorate, Indian-American Wars were considered to be a war on an external enemy.

- Compare R. Utley, Frontier Regulars, pp. 10–43.

- Interestingly, during the first years after the war, the officers who enjoyed a very good soldier opinion during the Civil War did not always fare as well in the West. The Fetterman massacre during the so-called Red Cloud War (December 1866) is a good example here. Native Americans killed every last one of the soldiers from the troop commanded by Captain William Fetterman who had been decorated during the Civil War; the situation was contained thanks to the cautiousness of Col. Henry Carrington, an unappreciated “paper pusher officer” with little experience of the battlefield. The probable cause behind Fetterman’s bravado and defeat is the lack of familiarity with the West and failure to adapt his fighting style the new opponent. Compare T. Clavin, B. Drury, op. cit., pp. 303–350.

- Compare Stephen E. Ambrose, Crazy Horse and Custer. Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors, New York 1996 (1st edition, 1975). See also: R. Utley, op. cit.; Ph. Weeks, op. cit.

- A lot is revealed about Custer’s style on the battlefield through the anecdote about one of his first feats, the pursuit of General Johnston’s confederate troops; upon crossing the Chickahominy river, he heard his commander, General Barnard, utter a rhetorical question: “I wish I knew how deep it is,” Custer rode his horse right into the middle of the river and yelled: “That’s how deep it is, Mr. General!”

- It is worth mentioning that immediately after the Little Bighorn, Custer was a controversial character in the press narrations; the cult of Custer the martyr was in full bloom only in the 1880s, see Ph. Weeks, op. cit., pp. 260–262.

- Ph. Weeks, op. cit., p. 186, R. Utley, Frontier Regulars, pp. 128–130.

- For a concise yet thorough and vivid biographical note on Mackenzie, see S. C. Gwynne, op. cit., pp. 329–348.

- Ibidem, p. 331.

- His body was also painfully marked with wounds; Mackenzie limped, he suffered from chronic back pain; at Winchester, he lost two fingers of his right hand.

- Orrin H. Bonney, Lorraine Bonney, Battle Drums and Geysers: The Life and Journals of Lt. Gustavus Cheyney Doane, Soldier and Explorer of The Yellowstone and Snake River Regions, Chicago 1970. See also Thomas W. Dunlay, Wolves for the Blue Soldiers: Indian Scouts and Auxiliaries with the United States Army, 1860–1890, Lincoln, Nebraska 1987, pp. 56, 96.

- During Sienkiewicz’s stay in the US, Doane distinguished himself in the American Army’s pursuit of the Nez Percé Indians in August and September of 1877.