Sienkiewicz’s Africa: The Great Unknown

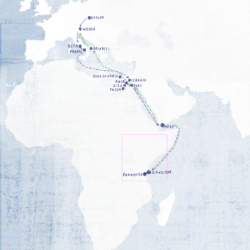

Henryk Sienkiewicz’s journey to Africa is beset by uncertainty and insecurity from the very beginning. The first and foremost imponderable is pretty obvious: where exactly is he heading? Zanzibar is only one of the options, others include Somalia and Abyssinia. Secondly, for a long time, it remains a total mystery what the travelers are going to do once they reach the African interior. Sometimes Sienkiewicz voices his doubt about them ever getting there at all, at other times he gets carried away with fanciful plans of getting to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro.[1] Also, the time scale of the journey seems to have been merely a matter of chance (to quote the letter of December 29, 1890, to the Szetkiewicz family: “I’ll probably arrive in Zanzibar only on January 17. We’ll see.”[2]). One might think that the health problems he experienced in Egypt managed to kill the remaining enthusiasm he had for the expedition, which was not high to start with. On December 21, 1890, Sienkiewicz wrote to Leo: “I’m going to Ismaila, Cairo, next to Zanzibar through Suez, and then…?? – One short trip into the interior, and I will ‘remove my person from the scene’ at the earliest opportunity.”[3] He even admits from time to time that he actually feels like coming back to Poland (“Zanzibar and other destinations do have their appeal, but it is nothing compared to the attraction of returning to one’s nearest and dearest. If I had a choice right now, it’s possible I would go home without thinking twice about it”[4]). This journey is clearly something to be checked off the bucket list and gotten over with as soon as possible before getting back to the Old Continent (“I will not stay here for more than ten days: I am going to take the first passable ship that sails to Europe. […] March will surely see me in Italy. In any case, I’ll be back in Europe by April”[5]).

On the other hand, in the letter of January 30, 1891, addressed to his mother-in-law, Sienkiewicz makes his journey sound like a stay in a seaside spa:

Dearest Ma,

I was thinking of returning home, but how can I take my poor sore throat back to the European winter, to unheated Italian rooms, under- or overheated railcars, then finally to the freezing temperatures of Kraków or Zakopane, etc. To be honest, Cairo is not a good option, either.

[…]

Here are the advantages of continuing on my travels: first, some clean and healthy air during the voyage; secondly, a doctor at my service; thirdly, a likelihood of reaching a better climate and healthier lands.[6]

It is not clear whether Sienkiewicz intended to proceed alone (which seems to be his inclination), or with Tyszkiewicz (whose presence, for unclear reasons, he is not particularly keen on). To appreciate this uncertainty, we need to look at deeper layers of the text. Sienkiewicz’s chaotic reflections make it difficult to gather the exact reason why he visited the Dark Continent at all (as mentioned above, we may assume that he wished to relive the American adventure and fulfill his vague dream of Africa triggered by Rogoziński’s reports[7]). Yet another important element is Sienkiewicz’s striking ignorance as to what he might expect once he arrives at his destination (wherever that is). He seems to erroneously believe, for example, that it is rain season in East Africa, and his published letters reiterate the false notion that tsetse flies are no health hazard to humans.

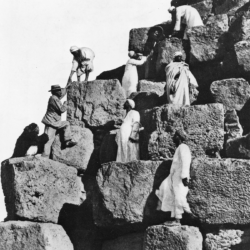

When the writer boarded the German steamer Bundesrath (eventually, in the company of Tyszkiewicz), it was already February, two and a half months after leaving Poland. The first-class luxury cruise took over two weeks (including a brief stopover in Aden). Sienkiewicz really did take advantage of this leg of his journey for convalescence. Five meals a day[8] and fresh sea air were supposed to help him recover before the expedition itself (whatever it was going to be).

Przypisy

- “Should Mount Kilimanjaro prove too much for me, especially for (?) my wallet, I would return immediately from Zanzibar, stopping over in Keren (Abyssinia)” (Listy [Letters], vol. 5, part 1, op.cit., pp. 308–309, emphasis B. Sz.; trans. J. M.).

- Ibidem, p. 305; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 3, part 1, op.cit., p. 495, emphasis B. Sz.; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 5, part 1, op.cit., p. 311; trans. J. M.

- Ibidem, p. 309, emphasis B. Sz.; trans. J. M.

- Ibidem, pp. 312–313; trans. J. M.

- “Almost anyone who is about to experience something extraordinary, something craved for, is full of foreboding that it will just pass them by. I was no exception when I was going to see subtropical Africa, which I have longed to do for a long time” (Listy z Afryki [Letters from Africa], op.cit., p. 25; trans. J. M.).

- “We are served food and drink throughout the day. There’s coffee between 7 and 8 a.m.; a hot meat dish for breakfast at 9 a.m.; lunch at noon; coffee at 3 p.m.; dinner at 6 p.m.; tea in the evening. Because there are only several passengers, everyone has their own cabin. Sweet and salt water baths are on offer, but I have not tried them yet” (Listy [Letters], vol. 5, part 1, op.cit., pp. 314–315; trans. J. M.).