The hunt, or making sense of Africa

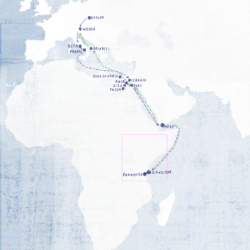

Throughout his stay on the Dark Continent, Sienkiewicz was not sure how to give meaning to this chapter of his life. Once the dream of the imagination-stirring Kilimanjaro was definitely over, the writer’s mind turned to hunting, which had been a major component of his American experience and, as such, offered a chance to recreate the excitement felt 15 years earlier. Nevertheless, while the “American” Sienkiewicz in all seriousness had called himself a dexterous shooter, the African alter ego tries to deflect potential disparagement with auto-irony: “Personally, were I as dexterous a hunter as I am an avid one, hundreds of hippopotamus wives would have to go into mourning for their murdered husbands.”[1]

Still, the hunt was supposed to become the focal point of the journey, especially with the reminiscences of Sienkiewicz’s achievements in bloody sports in America and Europe:

[…] I thought to myself that it wouldn’t hurt to add a dozen or so boxes of African trophies to my American and European collections; and Father Le Roy has just told me that, just a few hours away from Bagamoyo, in the Kingani River, we will see not one, not ten, but whole flocks of hippos.[2]

In a letter to Godlewski, he quips: “A lion was killed before I arrived on the scene. He evidently got wind I was coming for him, and chose to seek refuge in the arms of death.”[3] As before, Sienkiewicz and his companion run into difficulties caused by lack of knowledge and inadequate research into the realities of the region to be visited.

Father Korman confirmed what we had already learned from Friar Oscar in Bagamoyo: that this was the worst possible timing for a hunt. It was already March, which in the southern hemisphere marks the summer’s end period of the highest temperatures and drying mud puddles, when game withdraws into the mountains, hiding from the scorching heat in the shade of ravines.[4]

Sienkiewicz’s African hunting adventure is best epitomized by three episodes: shooting hippopotami from a boat, stalking land game during his stay in the mission house, and, finally, lion hunting. During the first episode, the hunters came close to death due to their ignorance as well as Sienkiewicz’s absent-mindedness.

A monstrous head with its maw open suddenly cropped up from under the water right next to us as if trying to sink its fangs into the side of our boat. […] Unfortunately, all I could think of was that, when shooting an animal in the head, you need a steel bullet, and I unproductively pulled on the trigger of the rifle I had just used. Tyszkiewicz, sitting on the other side of the boat, was not able to take aim, and the attacker managed to get away. There was just a sickening jolt when the beast must have brushed against the frames with its back, probably with the aim of tipping the boat over. It emerged a dozen or so meters away so that half of its body was visible, and I immediately took a shot, but then it went under water for good[5].

Tyszkiewicz recounts the incident in far more dramatic terms (though it seems that the only participant who fully grasped the actual degree of peril was their fellow hunter from Germany):

I am standing on the left side of the deck. The moment I am ready to fire, the boat is jerked so violently that I need to hold on to a servant not to fall into the water. The bouncing does not stop and I’m really getting scared, all the more so as our German companion is shrilly shouting some incomprehensible words at us. I turn around and see that, behind Sienk.[iewicz], there’s this enormous hippo holding the boat with the teeth and shaking it vehemently. […] Sienk.[iewicz] has lost his head: he is taking aim at the beast […] but the gun doesn’t fire – he has forgotten to cock it. Regaining my balance, I decide to shoot just in time. Just in time… for our foe to realize that it will not have its way with the solid steel boat and to let it go after a good farewell kick, leaving us with long faces, the German still screaming and scolding us.[6]

To sum up, the hunters had a lucky escape without even realizing what was going on, with no trophies to show for it, risking their lives in a way that was, at best, unnecessary.

The second episode, i.e. hunting in the vicinity of the Mandara mission house, was described as a series of fails by both Sienkiewicz and Tyszkiewicz. In the straightforward words of the latter:

This hunt was a failure in every possible respect. Le Père Supérieur was rushing forward, completely oblivious to his duties as a host and to his tired guests, who were scarcely able to keep up with him. To make things worse, Sienkiewicz was still suffering from a fever. I learned later that there had been some misunderstanding between the two, that’s why neither of them was in a good mood. We could see a lot of antelopes but I was the only one who found himself in a position to shoot. I wounded a fine specimen, but in the end, was not able to trace it down.[7]

Sienkiewicz, in turn, commented on the trip as follows:

There were only two good things that came out of the hunt that day. First, we saw antelopes, without which we could never say we saw Africa in its full natural beauty. Second, cutting across towards M’Pongwe at a breathtaking pace, we covered an enormous distance, at least twice as long as our usual daily treks.[8]

The matter is also discussed in Sienkiewicz’s letter to Godlewski:

My hunting plans partly foundered since the “real thing” was supposed to start only in Gugurum. While trekking, I could see antelopes, but only from a distance of 600 meters. Besides, when you’re hiking, you are usually short of breath, with your arms and legs shaking and your heart pounding; it is very hot, and you’re bound to shoot like an amateur. A couple of times, I even missed the birds that were not even moving – this has never happened to me in Europe.

Still, I killed a lot of birds altogether. I could hear monkey noises, but they never once came in my sight. And that’s about it.[9]

The lion hunt scheduled for the end of the journey was prevented by Sienkiewicz’s bout of fever, which itself could serve as some sort of a punchline to the rather miserable story of hunting as a synecdoche for the African expedition. Sienkiewicz made up for the missing trophies in Zanzibar, buying souvenirs in bulk: “My baggage load increased every day. I bought several dozens of those superb Madagascar mats, a leopard skin, an enormous rhino horn, and many other choice items. Elephant tusks turned out to be so expensive that I sadly had to renounce the purchase.”[10]

Przypisy

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z Afryki [Letters from Africa], op.cit., p. 109; trans. J. M.

- Ibidem; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 1, part 2, op.cit., p. 156; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z Afryki [Letters from Africa], op.cit., p. 228; trans. J. M.

- Ibidem, p. 168; trans. J. M.

- J. Tyszkiewicz, op.cit., p. 106; trans. J. M.

- Ibidem, p. 110, emphasis B. Sz.; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z Afryki [Letters from Africa], op.cit., p. 233; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy [Letters], vol. 1, part 1, op.cit., p. 159; trans. J. M.

- H. Sienkiewicz, Listy z Afryki [Letters from Africa], op.cit., p. 259; trans. J. M.